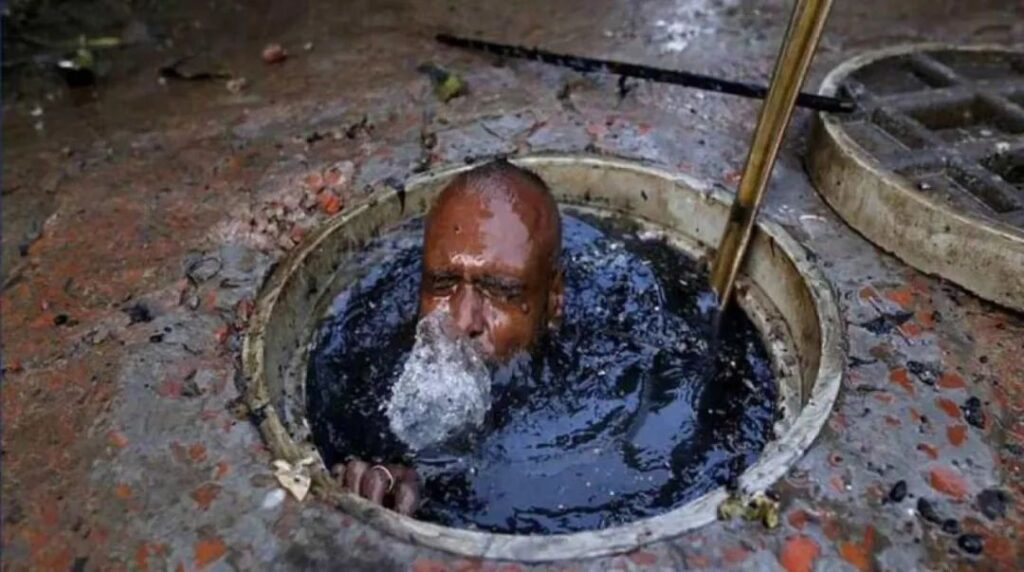

In India, there exists a group of workers known as “Manual Scavengers.” Despite the name suggesting they are cleaners, their daily task is not to deal with household waste but with human excrement containing various deadly bacteria.

In regions with underdeveloped modernization, clogged sewers, dry latrines, drainage channels, and septic tanks are not easily cleared by machines, or bosses save costs by not using advanced equipment, so people are sent down to “scoop out” feces and unclog pipes. These scavengers receive almost no protective gear; they have no goggles, masks, or specialized protective clothing, often working in thin pants and shoes or even naked, immersed in the nauseating filth and wastewater.

Illustration of Manual Scavengers

They repeatedly sink into the dark, murky sewage, scooping out feces with buckets or shovels, then transporting them in wheelbarrows or baskets to processing sites, sometimes kilometers away.

Transporting feces to distant fields

Due to prolonged exposure to viruses, pollutants, chemical waste, and inhaling large amounts of toxic gases, many scavengers suffer from serious illnesses, including burns, respiratory problems, skin and blood infections, eye and respiratory infections, or suffocation in sewers… Their expected lifespan is only 40 years, often even less in reality. Data collected by the organization “Safai Karmachari Andolan (SKA),” which works to improve the working conditions of scavengers, shows that from 2017 to 2018, the average age of deceased scavengers was only 32. It’s reported that approximately 600 scavengers die each year from various causes, with the media describing it as “the world’s most dangerous job.” Yet, despite the high risk, scavengers struggle in these “death pits” due to their livelihood, earning only 320 INR (about 27.5 RMB) a day…

Illustration of Manual Scavengers

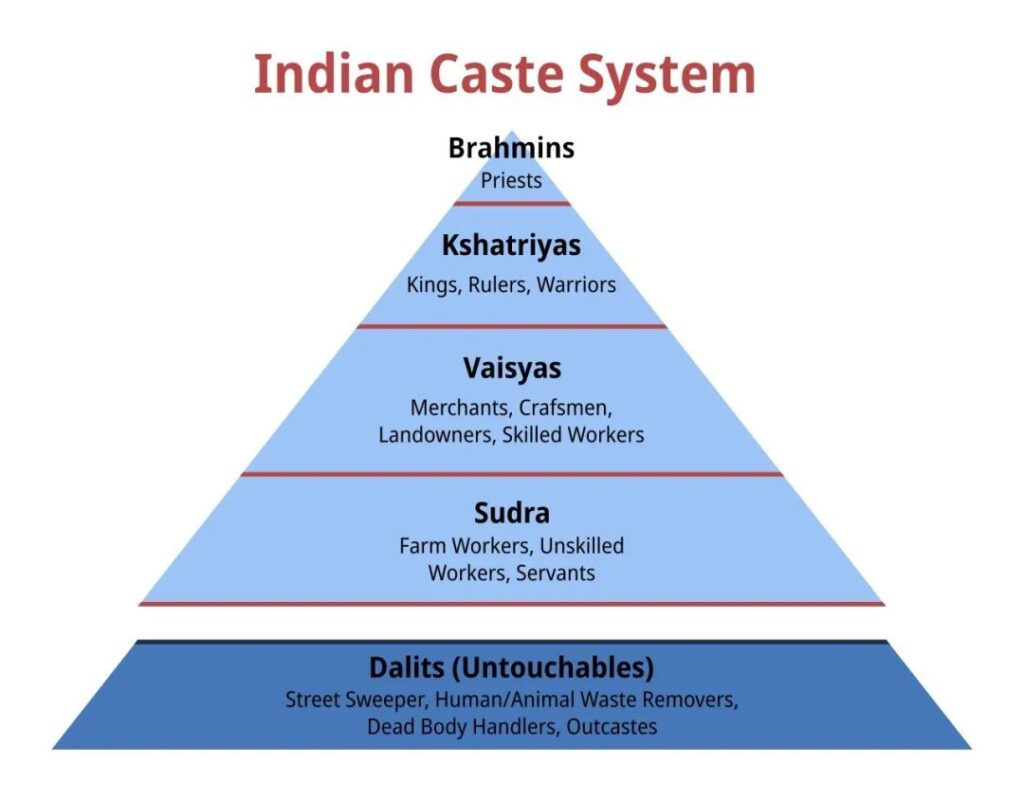

This inhumane work has led to countless protests, and India has indeed legislated against it, but implementation is another matter. According to SKA’s investigation, over 770,000 people are still engaged in this work. One major reason for the lack of attention to this issue is that nearly all who do this work belong to the lower caste, the Dalits, who are at the bottom of society. Despite the caste system being legally abolished, its influence remains deeply ingrained, and people still believe that lower castes are naturally suited for dirty, “lowly” labor. Vimal Kumar, the founder of the Movement for Scavenger Community, comes from the Dalit caste. His mother was a scavenger, using the meager wages earned from cleaning feces to send him to school, but she died of lung cancer due to continuous dust inhalation. When teachers and classmates learned of Kumar’s background, instead of helping, they collectively bullied him. Reflecting on his experiences, he described it as: “Society believes we are born to clean others’ feces. We are discriminated against in every aspect of life.” In a way, manual scavengers are the product of social feudal thought and collective bullying. Under this climate, many Dalits who become scavengers see their children also becoming scavengers, perpetuating a cycle of low-wage work with no chance of improving their status or escaping poverty.

Caste system in India

Without assistance, they must find ways to cope. Many turn to alcohol to numb their senses against the stench of feces, but entering sewers while intoxicated often leads to accidental deaths… Their passing often means the loss of the family’s primary breadwinner. Anjana from Gujarat received the sudden news of her husband Umesh Bamaniya’s death in April last year while cleaning a sewer. His body was found covered in wastewater. He was only 23 years old, just 10 days before their son was born… In one day, she lost the husband responsible for supporting the family, leaving her in despair, wondering, “How will I raise and educate my child?” The same tragedy befell Annamma from Tamil Nadu, whose husband suffocated in a factory’s sewer last September, leaving her and her two young daughters bewildered…

Illustration of Manual Scavengers

Tragically, the families of the deceased often receive no compensation. Ratnaben’s husband died in 2008 while working in a factory’s sewer due to toxic gas inhalation. The management promised various compensation measures at the time, but 15 years later, she has received nothing.

Desperately, as long as the mindset does not change, they will continue to endure this unjust treatment…