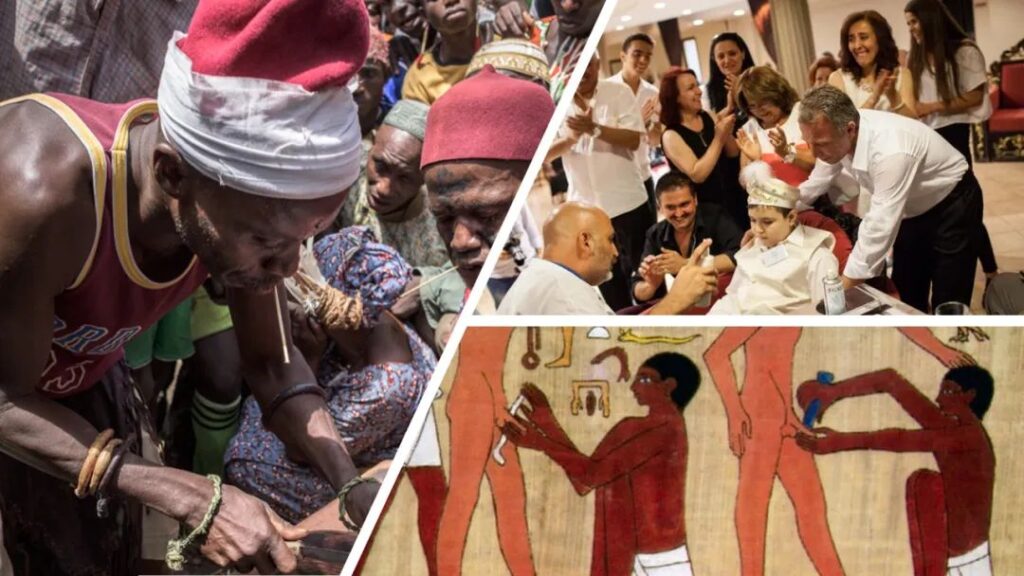

We are all familiar with male circumcision, a practice that involves the removal of the foreskin. It is considered one of the oldest and most widespread surgeries in the world. Evidence of male circumcision dates back to around 6000 BC in ancient Egypt and even earlier in the Paleolithic era. In many religious beliefs, such as Judaism and Islam, male circumcision is a fundamental ritual.

In countries like the United States, Canada, Australia, South Korea, and various regions in Africa, circumcision is often performed on newborns or during adulthood as a cultural or religious rite. Today, male circumcision is often carried out for health reasons, such as treating phimosis or preventing sexually transmitted infections like HIV and HPV.

However, when it comes to female genital mutilation (FGM), the situation is vastly different. FGM is a dangerous and harmful practice that involves the partial or complete removal of the female genitalia and is a severe violation of human rights.

What is Female Genital Mutilation (FGM)?

Female genital mutilation, as defined by the World Health Organization (WHO), refers to “all procedures that involve partial or total removal of the female external genitalia or other injury to the female genital organs for non-medical reasons.” This practice is most commonly performed on girls between infancy and puberty, though it can also occur in adulthood.

The procedure is typically carried out by traditional practitioners who are not trained medical professionals. Often, these procedures take place without any form of anesthesia or sterilization. In some cases, a family member holds the girl down while a razor, glass, or knife is used to cut off parts of her genitalia. In extreme cases, the vulva may be stitched up, leaving only a small opening for urination and menstruation.

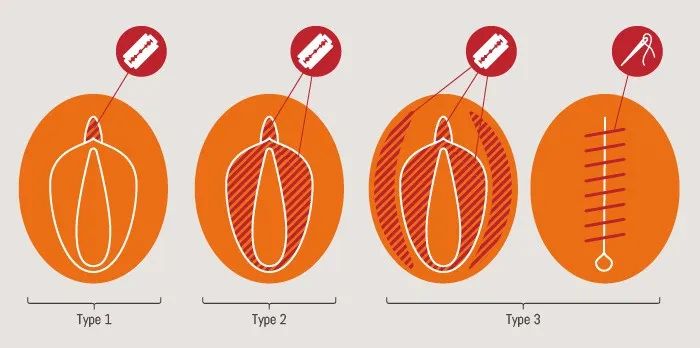

WHO defines FGM in four types:

- Type 1: Removal of the clitoral head and/or the clitoral hood, which is most common in Egypt and southern Nigeria.

- Type 2: Removal of the clitoral head, the clitoral hood, and parts of the labia minora, with or without the removal of the labia majora.

- Type 3: Known as infibulation, this involves narrowing the vaginal opening by removing parts of the labia minora and/or majora and stitching the remaining skin together. This is the most extreme form and is most prevalent in northeastern African countries such as Djibouti, Eritrea, Ethiopia, Somalia, and Sudan.

- Type 4: All other harmful procedures, such as pricking, piercing, scraping, or cauterizing the female genitalia, are included here. This type is commonly practiced in parts of Indonesia and some Eastern and Southern African regions.

The History and Current Situation of FGM

FGM has been practiced for over 2000 years, with origins that are somewhat unclear. It is believed to have emerged in patriarchal societies or cultures in Africa, where it was considered a traditional social practice. FGM was often viewed as a means to control female sexuality, promoting chastity before marriage and loyalty afterward. It was seen as a way to maintain a woman’s “purity, beauty, and honor.”

As early as the 2nd century BC, Greek geographers documented FGM practices along the eastern coast of the Red Sea, where girls or young women were subjected to circumcision. Mummified remains from 5th century BC Egypt also show evidence of this practice. Interestingly, today, FGM is known as “Pharaoh’s circumcision” in Sudan and “Sudanese circumcision” in Egypt.

Some believe FGM originated as a way to protect women from rape, particularly among equatorial African pastoralists. Research indicates that FGM may have been linked to the transatlantic slave trade (1400-1900). During this period, African women were sold as slaves in the Islamic Middle East, and FGM was performed to ensure that a girl’s virginity could be preserved, making her more valuable as a slave.

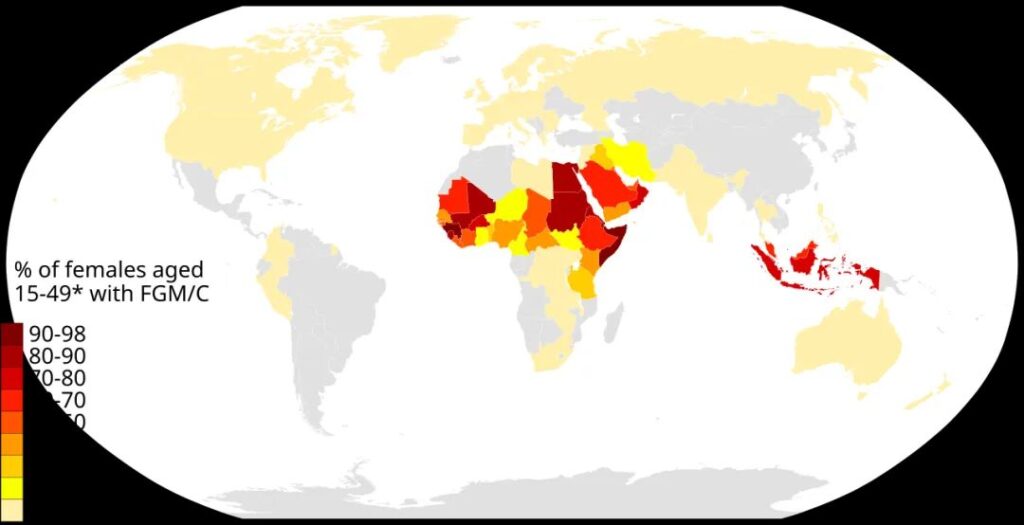

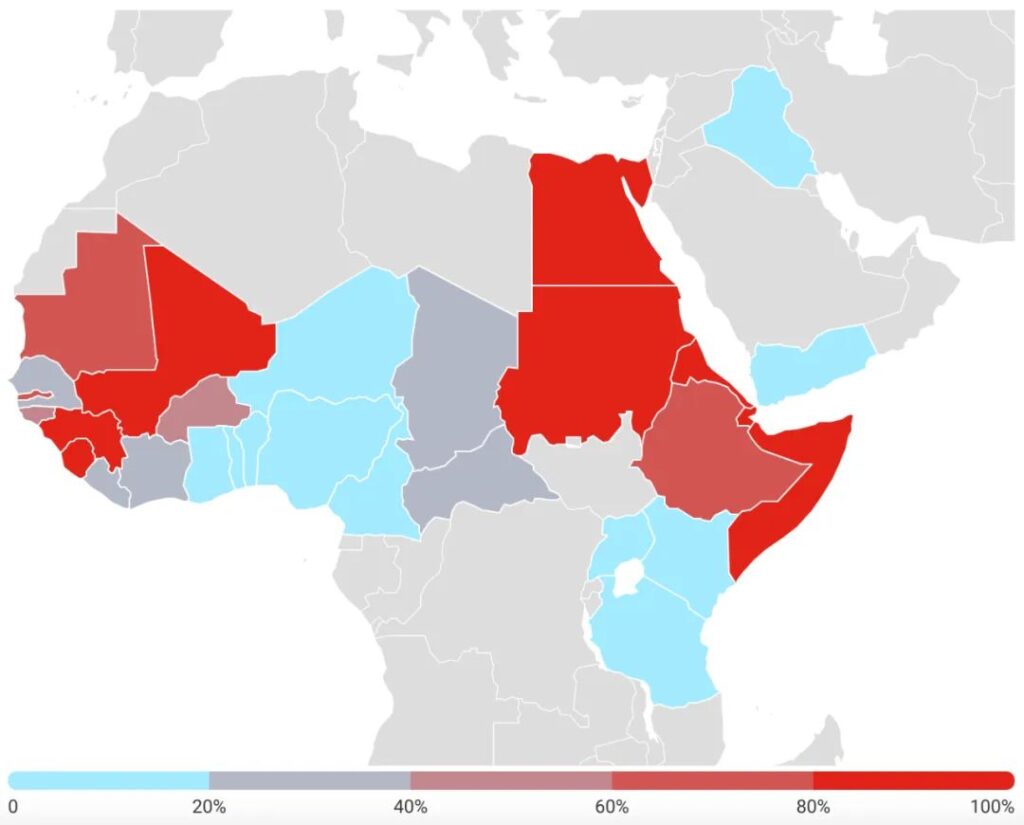

Today, FGM remains widespread across the globe and continues to be carried out, especially in African countries. It has spread to other regions due to migration, further entrenching the practice in many cultures.

According to the 2020 Global Report, an estimated 2.3 million girls and women aged 15-49 have undergone FGM across 31 countries. Of these, 1.44 million live in Africa, 8 million in Asia, and 6 million in the Middle East. The practice is still carried out on 3-4 million girls each year.

The Dangers of FGM

There is absolutely no health benefit to FGM, and it causes numerous serious consequences for women and girls. The extent of the harm depends on the type and severity of the procedure. FGM not only damages the female genitalia but also affects overall physical and psychological well-being.

Short-Term Complications:

- Severe pain and bleeding

- Tissue swelling

- Infections (e.g., tetanus)

- Difficulty urinating

- Wound healing complications

- Permanent damage to surrounding genital tissues

- Shock, or even death

Long-Term Complications:

- Pain during urination

- Chronic vaginal and urinary tract infections

- Menstrual problems

- Scarring and keloids

- Painful intercourse

- Reduced sexual satisfaction

- Complications during childbirth (e.g., prolonged labor, excessive bleeding, need for C-sections)

- Increased risk of newborn death

- Psychological issues, including anxiety and depression

Warda Hassan Mahmoud (pictured above) is a survivor of FGM. She was subjected to the practice at age 6, and she describes it as the most painful experience of her life. “The trauma has never left me. That’s why I’m actively working to stop FGM and raise awareness about its dangers.”

Internationally, FGM is recognized as a severe violation of women’s and girls’ human rights. It is a deeply rooted expression of gender inequality and extreme discrimination against women.

Global Efforts to Eliminate FGM

In 2008, the World Health Assembly passed a resolution (WHA61.16) urging the elimination of FGM. This resolution emphasized the need for coordinated efforts across all sectors, including health, education, justice, and women’s affairs.

The United Nations Children’s Fund (UNICEF) and the United Nations Population Fund (UNFPA) have led the world’s largest efforts to end FGM. They launched a 30-year program, starting in 2008, to end the practice through education and legislation, working with governments and communities.

The program aims to raise awareness about the harmful effects of FGM, shift social norms, and enforce legal frameworks against it. It also focuses on providing medical and psychological care for survivors.

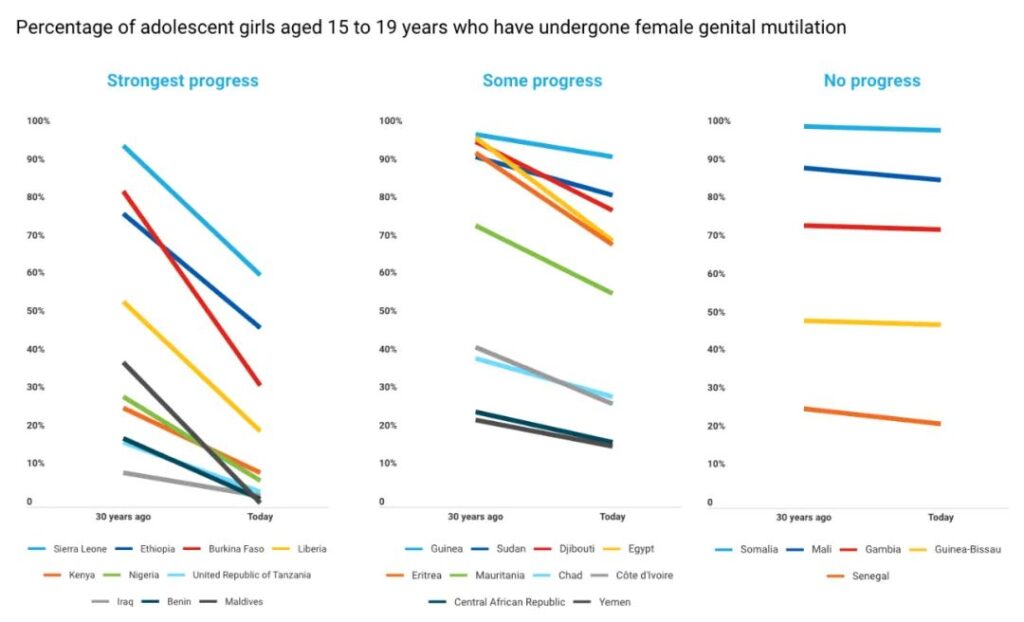

According to the 2024 report by UNICEF, 13 countries have passed laws banning FGM, which has helped over 6 million girls and women access services related to prevention, protection, and treatment. In 15 countries, around 45 million people have publicly declared their intention to abandon the practice.

The report highlights that progress is accelerating, with half of the improvements made in the past decade alone. Countries like Kenya, Sierra Leone, and Egypt have seen rapid declines in FGM rates.

However, despite these successes, the data also shows that the pace of progress is slower than population growth. The current global decline rate needs to be 27 times faster to end FGM by 2030.

Conclusion: Respecting Women’s Rights and Protecting the Future

While FGM remains a deeply ingrained tradition in certain cultures, global efforts continue to make progress toward eliminating it. With increased awareness, education, and legislative action, the goal is to protect the health and rights of women and girls everywhere. Ending FGM is not just a matter of legal frameworks but also requires a profound cultural shift and collective global action. The hope is that one day, all girls will grow up in a world where they are free from this harmful practice, and their rights, dignity, and health are fully respected.