For people living in pre-modern societies, the threat of plague was no laughing matter. Highly contagious and deadly diseases periodically swept the globe, devastating local communities and leaving people in fear of infection.

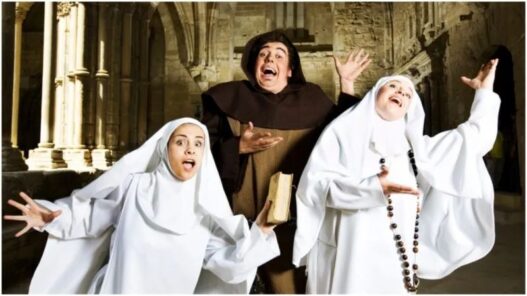

However, in 16th-century Strasbourg, a different kind of plague enveloped the city. The so-called “dancing plague” did not cause fatigue, fever, and pustules but instead triggered a collective frenzy, where city residents danced relentlessly in the streets until they collapsed from exhaustion and died.

Hendrick Hondius’s engraving depicting three women affected by the dancing plague.

In the hot summer of 1518, Strasbourg experienced an event known as the “dancing mania,” also referred to as the dancing plague. A chronicle from 1636 describes the event as follows:

“[In this year], there appeared among the people a notable and terrible disease, known as St. Vitus’s Dance. People danced day and night in madness until they finally fainted and died.”

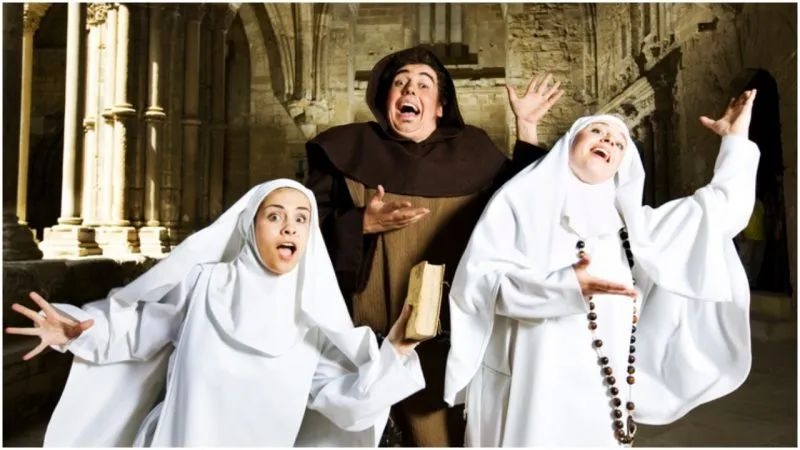

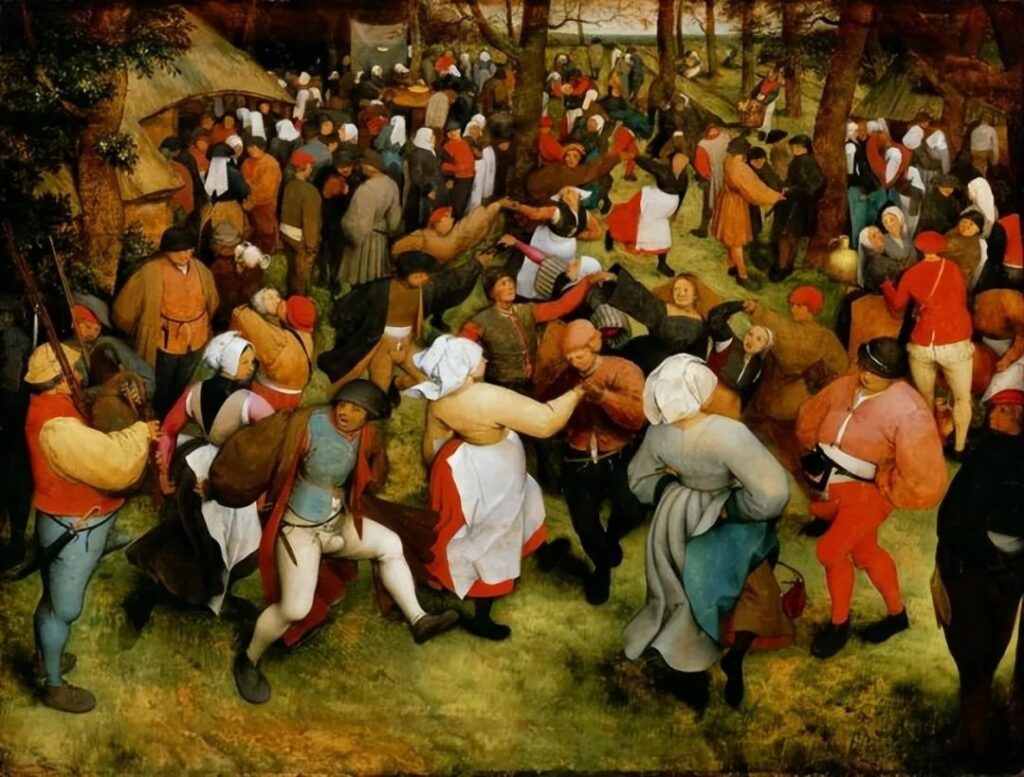

Pieter Bruegel the Elder’s work “The Wedding Dance” (circa 1566).

According to historian John Waller, this plague is said to have begun with a woman named Frau Troffea. Many at the time believed it was the revenge of St. Vitus, the patron saint of dancers, actors, and entertainers, who intended to punish the people of Strasbourg for their immoral behavior.

On a hot July morning, Frau Troffea spontaneously began to dance maniacally in the street outside her home. She danced all day, even into the night, until she collapsed from extreme fatigue. The next day, she rose again and continued dancing, ignoring all attempts to persuade her to rest.

Dancing Girl, 1888.

As described by Waller, this increasingly frenzied behavior continued for days, attracting a large number of onlookers who were fascinated by the woman’s strange actions. Local clergy, concerned that the dancing might become contagious, forced her to seek healing at the nearby shrine of St. Vitus.

Frau Troffea was successfully treated at the shrine, but it was too late to stop the spread of the mania. Local residents who witnessed her dance soon began to imitate her, with more people joining each day.

On the city’s squares and streets, hundreds of dancers convulsed, flailing their arms and spinning their bodies, creating a scene of chaos. In the hot summer sun, they sweated profusely, with many collapsing from dehydration and fatigue, their feet bleeding.

Painting by Pieter Bruegel.

Initially, local doctors were at a loss on how to help these souls clearly in distress. They initially encouraged dancing, believing it necessary to expel the disease through movement. However, when this approach failed to yield results, they decided to ban the playing of music and instruments.

Eventually, local clergy intervened, sending the afflicted to the shrine of St. Vitus in hopes of appeasing the angry saint. After a month of dancing mania, the plague seemed to subside, and life in Strasbourg returned to normal.

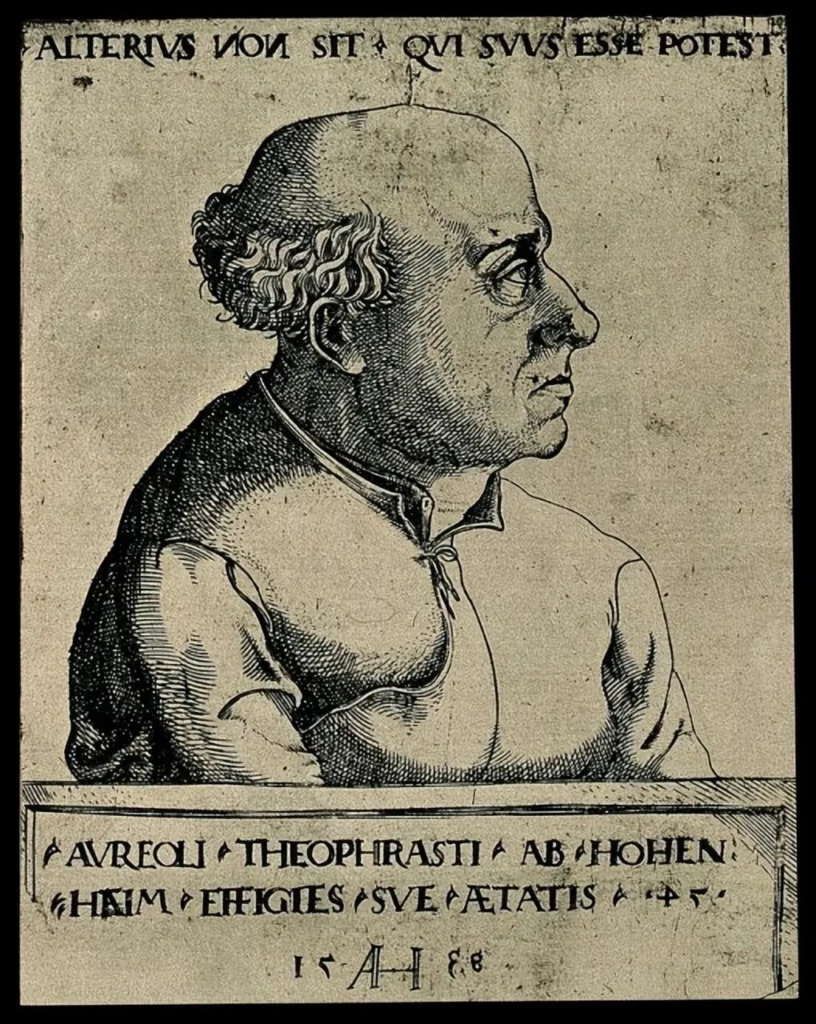

St. Vitus

However, the plague left a trail of destruction. Although the number of deaths is unknown, some commentators believe that hundreds might have perished during that frenzied summer.

Various theories have been proposed regarding the origins of this collective madness. The famous alchemist Paracelsus, who visited the city years later, believed that Frau Troffea had intentionally started dancing to shame her husband, with other women’s mimicry being a serious form of female rebellion.

Modern historians speculate that these dancers were victims of hallucinations caused by consuming rye infected with ergot fungus.

However, historians like John Waller now believe that this madness was caused by a combination of social and economic factors, including poor harvests, political instability, and the prevalence of disease.

The hardships of the time could have triggered a psychological contagion, not uncommon in societies under extreme stress, which in this case manifested as relentless dancing. Regardless of the cause, the dancing plague of Strasbourg remains one of the city’s most bizarre events in history.