Rome was once one of the most powerful empires in the world, especially during the Pax Romana era, particularly from the 1st to the 2nd century AD under the rule of the Five Good Emperors (96 to 180 AD). During this time, the Roman Empire reached its peak in politics, economy, military, and culture.

Marcus Aurelius

Marcus Aurelius was an emperor of ancient Rome, ruling from 161 to 180 AD. He is known for his philosophical thoughts and his work “Meditations,” making him a philosopher-emperor of the Stoic school. His reign is considered one of the golden ages of the Roman Empire, despite facing challenges from border wars and internal unrest. Marcus Aurelius is respected by posterity for his wisdom, rationality, and love for philosophy.

The Cliffs Against Which the Waves Break

In his “Meditations,” Marcus Aurelius wrote: “be like the cliffs against which the waves break and break,” meaning “be like the cliffs that the waves crash upon but do not break.” This metaphor suggests that a person or thing, when faced with difficulties and challenges, can remain steadfast and unshaken, just like the cliffs that stand firm against the constant pounding of the sea, symbolizing resilience and an unyielding spirit.

Under the mighty onslaught of the Roman Empire, eight countries stood firm like these cliffs, thwarting the conquest dreams of Roman emperors.

Sudan

The one-eyed warrior queen Amanirenas of Kush should be more renowned in history. During the reign of Emperor Augustus, the Roman governor of Egypt imposed taxes on the Kingdom of Kush, which the Kushites did not consider themselves part of the Roman Empire. In anger, Amanirenas attacked Roman territory, crossed the Nile, brought back captives, spoils, and the head of a statue of Augustus, which she buried under the steps of her palace to humiliate the emperor.

Her actions triggered a long war with Rome. Despite occasional victories by Roman legions, Amanirenas relentlessly counterattacked, even losing an eye in battle. Ultimately, the Roman governor of Egypt capitulated to her in 21 BC through the Treaty of Samos, securing sovereignty for Kush, which was seen as a substantive surrender by Rome. The treaty lasted for centuries, with Roman forces no longer attempting to conquer southward.

Yemen

The Romans held Yemen in high regard, naming it “Arabia Felix,” one of the three “Arabias,” due to their admiration for the region’s wealth and climate. However, this admiration soon turned into a desire for conquest. In 26 BC, Emperor Augustus ordered the governor Aelius Gallus to attack Yemen, guided by the Nabataean Syllaeus.

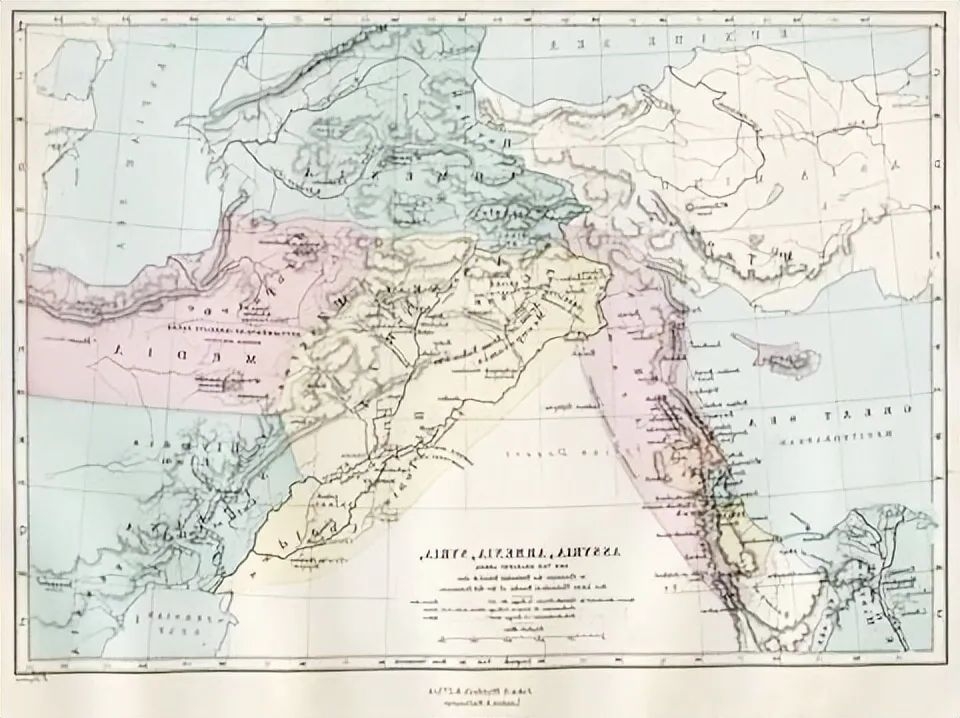

A 15th-century map of the Middle East.

Syllaeus, therefore, adopted a cunning strategy, leading Gallus through the harshest, most desolate routes of the Arabian Peninsula. By the time Gallus’s troops reached Yemen, they were nearly exhausted, plagued by hunger, disease, and extreme thirst. In such conditions, they were unable to conquer Yemen and were forced to retreat to Egypt. Ultimately, Yemen remained unconquered by Rome.

Scotland

Then known as Caledonia, Scotland was a thorny issue for Roman commanders. Rome made three attempts to conquer Scotland but abandoned each one. Contrary to common belief, Romans did cross Hadrian’s Wall and briefly reached the Antonine Wall.

The Antonine Wall

Unlike Hadrian’s Wall, the Antonine Wall is located within modern-day Scotland. Ordered to be built by Antoninus Pius in 140 AD, this line marked the northern boundary of the Roman Empire but failed to effectively protect it. The Caledonians ignored this wall, continuing to raid across it throughout the occupation.

Ireland

The Romans called Ireland Hibernia, meaning “the land of eternal winter,” which was not an attractive description. Due to these negative impressions, the Romans seemed uninterested in occupying Ireland.

Ireland had no road to Rome.

However, Agricola, who ruled Britain from 77 to 84 AD, considered invading Ireland. He gathered information from an Irish prince, believing that only one legion would be needed to conquer Ireland. Yet, Agricola seemingly never undertook this invasion. Although some historians argue that the satirist Juvenal’s works imply Agricola landed in Ireland, the nature of the text makes interpretation unclear. Archaeological records clearly show that neither Agricola nor any other Roman successfully conquered Ireland.

Iran

The wars between Rome and Parthia began before the establishment of the Roman Empire and continued after Parthia’s fall. Historians divide the conflicts into four main periods. Despite periods of peace and diplomacy, anti-Parthian sentiment was a significant part of Roman politics. Parthia humiliated Rome several times, including defeating Roman forces at the Battle of Carrhae and pouring molten gold down the throat of the Roman commander Crassus as an insult.

In 116 AD, Emperor Trajan conquered the Parthian capital of Ctesiphon, which was seen as a glorious victory. But, like most of Trajan’s conquests, the occupation of Ctesiphon did not last. A rebellion that year led his successor Hadrian to abandon the city. His Sasanian descendants continued the tradition of Parthia, engaging in long, fruitless wars with Rome.

Armenia

Rome never managed to secure a stable conquest of Armenia. Although Trajan occupied Armenia for three years, his successor Hadrian chose to withdraw. This was not because conquering this small mountainous nation was beyond the capabilities of the Roman legions, but because Armenia became a political focal point in the tug-of-war between Rome and its rival, Parthia.

A 19th-century map of Assyria, Armenia, Syria, and neighboring regions.

Rome repeatedly tried to ensure that the Armenian monarch was a direct or de facto client of the empire.

Poland

In Roman times, archaeologists found the Przeworsk culture inhabiting the area now known as Poland. Romans mentioned a tribal confederation called the Lugii, which modern historians link to the Przeworsk culture. The Romans seemed not to attempt to conquer the Lugii. Instead, in 92 AD, Emperor Domitian sent 100 cavalrymen to support the Lugii in their fight against the Suebi.

Germany

Rome’s failure to conquer Germany is quite famous. One could even argue that, in the end, Germany conquered Rome, as Germanic tribes sacked Rome in 410 AD. Conflicts with Germanic tribes troubled Rome for centuries, affecting trade and even leading to the assassination of several emperors. After the catastrophic defeat at the Battle of Teutoburg Forest, Rome was forced to abandon its dreams of expanding into and conquering Germanic territories. This battle has been called “one of the most destructive defeats in the history of the Roman legions.”

A forest in Bavaria, Germany.

In 9 AD, the Germanic leader Arminius annihilated three Roman legions in just four days, forcing the legion’s commander to commit suicide. This victory was extremely decisive. A few years later, the Roman commander Germanicus attempted to avenge the fallen legions, but Rome was already shocked and defeated, unable to control the land where their soldiers were buried.