In 1864, Paris introduced a new form of “theater” that quickly became immensely popular. It was free to the public and open seven days a week. Street vendors lined up outside, selling fruits and nuts to the curious tourists and passersby waiting in line. Once inside the dim, silent exhibition hall, attendants would pull back the curtains to reveal a shocking scene: corpses. This was the everyday spectacle at the Paris Morgue.

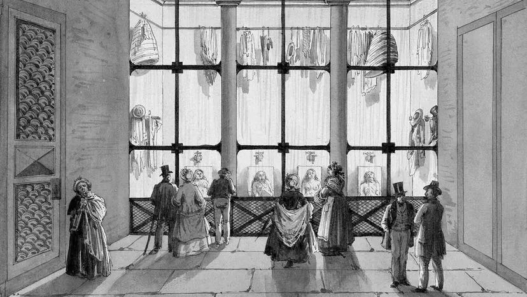

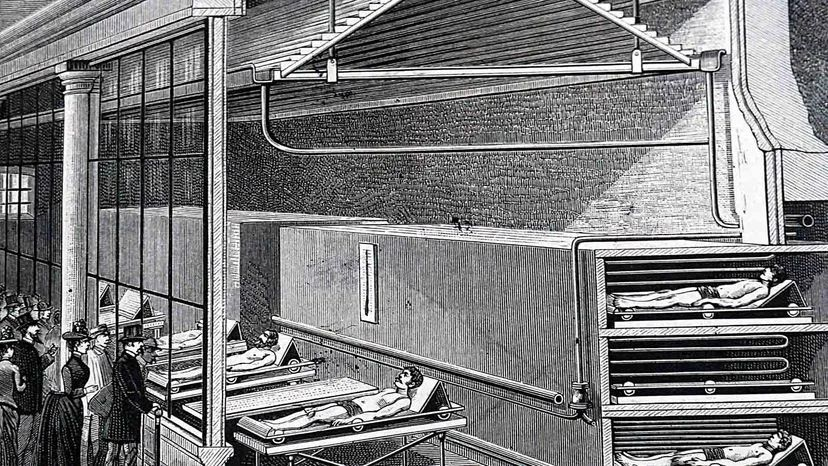

This painting depicts how people in the mid-19th century would observe the unidentified bodies at the Paris Morgue. Before refrigeration systems were invented, morgues used to drip cold water on the bodies to slow down the decomposition process.

Although it sounds eerie, the Morgue was one of the most popular attractions in Paris in the late 19th century. As many as 40,000 people a day would visit the morgue, gazing at the half-naked, decaying bodies—many of which had been pulled from the nearby Seine River—displayed on marble slabs behind glass windows. It was even referred to as the “Death Museum” in English travel guides (Le Musée de la Mort).

The morgue’s official purpose was to recruit the public’s help in identifying unclaimed bodies. However, as Vanessa Schwartz, Professor at the University of Southern California and author of Spectacular Realities: Early Mass Culture in Fin-de-Siècle Paris, points out, it was much more of a show. She presents a convincing argument that the Paris Morgue, along with the city’s wax museums and sensational newspapers, created a form of “real-life” or “true crime” entertainment that the public couldn’t get enough of.

Paris: The “Viewing Culture” of the First Modern City

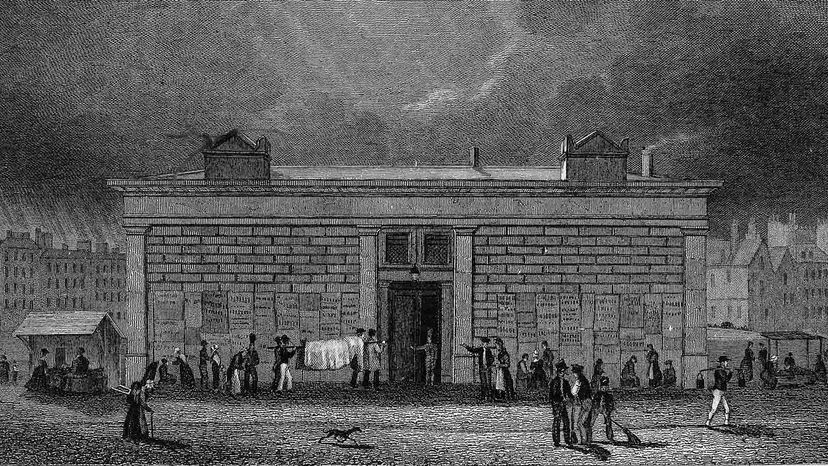

In the 1850s, Napoleon III (nephew of Napoleon Bonaparte) launched an ambitious project to transform Paris from a medieval city with narrow, maze-like streets into a modern metropolis. The new city boasted broad boulevards, spacious parks, and marvels like underground drainage systems.

Faced with this open, walkable city, Parisians coined the term flânerie, which refers to the urban pleasure of aimless wandering. Schwartz highlights that Paris was also the first city to establish department stores, which provided a new shopping experience.

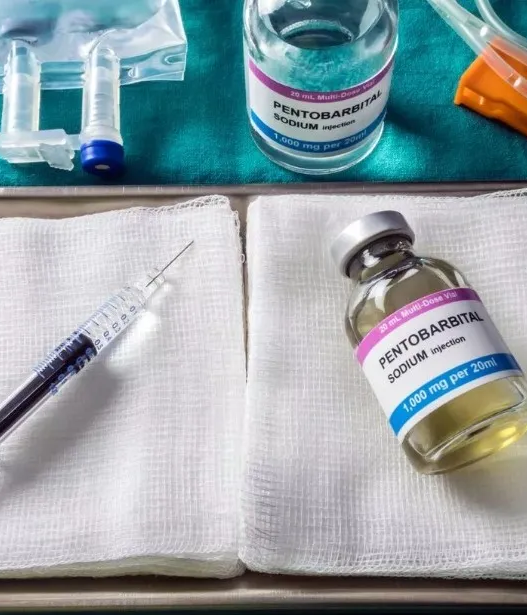

This sketch depicts the Paris Morgue before the city’s renovation and its relocation near Notre-Dame Cathedral.

“It was the first time you could walk into a store just to look,” Schwartz says. “In Paris, there was a ‘viewing culture,’ where the city became something to consume visually.”

The Morgue was part of this transformation. It was a thoroughly modern building located behind the famous Notre-Dame Cathedral, where unclaimed bodies could be carefully processed, washed, examined, and then displayed for public identification.

But before long, the morgue became another curious spot to “consume” for the flâneurs. With its dramatic curtains and ever-changing cast of “characters,” the morgue became one of the attractions people would flock to. Schwartz quotes a 1869 commentator who described the crowd at the Morgue: “They came only to look, just as they read serialized novels or went to the Ambigu (a comedy theater); at the door, they shouted to each other, asking, ‘What’s inside?'”

The Real-Life Wax Museum

The wax museum was another 19th-century invention with some interesting similarities to the Morgue. Both aimed to create a “real wonder.” Early Paris wax museums not only displayed famous historical figures but also showcased current news events. Grévin Wax Museum (still in operation today) was founded by journalist Arthur Meyer, who wanted to make newspaper reports come alive. The more lurid scandals or grisly murder cases, the more they attracted readers to “watch” these stories in the wax museum.

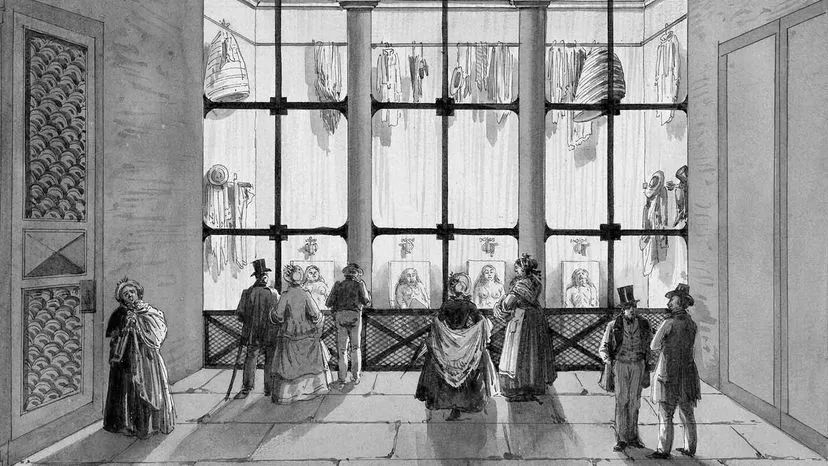

By 1882, the Paris Morgue had installed the most advanced refrigeration systems, allowing bodies to be preserved for weeks.

The same thing happened at the Morgue. The most attention-grabbing displays were often those of women or children who had died under tragic or mysterious circumstances. When a child or young woman was brought to the Morgue, newspapers would extensively report on it, drawing crowds of visitors. Even morgue staff and city officials got involved, sometimes dressing the bodies of the deceased children in fine clothing, or staging “confrontations” when suspects were arrested by the police.

In 1882, to extend the display time, the Morgue installed state-of-the-art refrigeration systems. Before this, when bodies decomposed too quickly, staff would substitute them with lifelike wax figures to satisfy the public’s curiosity. One famous case involved the “Woman Cut in Half” in 1976, whose body was displayed in such a state, attracting a large number of visitors. Later, the wax figure replaced the body to continue the “performance.”

Schwartz points out that about 300,000 to 400,000 people came to witness this combination of crime victims’ bodies and realistic wax figures.

19th-Century Descriptions of the Morgue

To understand what it felt like to visit the Paris Morgue, French writer Émile Zola vividly described the experience in his 1867 novel Thérèse Raquin. The Morgue was a spectacle open to everyone, attracting people from all social classes. Some even went out of their way to visit the “performance of death.” If there were no bodies on display, visitors were disappointed. But if there were, they expressed their emotions as if they were at the theater, sometimes even applauding or whistling as they left, satisfied.

Around 1910, a horse-drawn hearse stopped outside the Paris Morgue. By 1907, the public exhibition hall in the Morgue was completely closed.

However, not everyone appreciated these exhibitions. A Harvard student in 1885 described his negative impressions of the Morgue: “The eager crowd crowded around the windows, old women were gossiping loudly, ladies with pale faces staring without blinking, and children were being hoisted up to get a better view. The scene was disturbing.”

For moral reasons, the public exhibition hall of the Morgue closed in 1907. The vendors who relied on the tourist traffic were disappointed. One writer sarcastically commented that the Morgue was like a free theater for the people, which had now been canceled. It seemed that social justice was yet to arrive.