With over 1.7 billion people, South Asia is one of the most densely populated regions on Earth. Thanks to trade, colonization, migration, and labor export, the flavors of Indian cuisine have traveled across continents and centuries. Let’s explore how iconic Indian dishes like curry, biryani, roti, and ghee have become global staples.

Curry – The Most Famous, Yet Misunderstood Indian Dish

The Origin of Curry

While “curry” is often associated with India, the term itself is more Western than Indian. In India, you’re more likely to hear the word masala, which refers to a mix of spices rather than a specific dish. The use of spices dates back over 4,000 years to the Indus Valley Civilization, where mustard seeds, cumin, and fennel were used.

India’s hot and humid climate encouraged spice use for flavor, preservation, and even medicinal benefits. What the world now calls “Indian curry” varies widely across regions—vegetarian curries in Hindu households, meat curries in Muslim kitchens, and seafood curries along coastal areas.

Curry’s Journey Across Asia

Through trade and migration, Indian cooking influenced Southeast Asia. Thai curries use coconut milk and sugar; Burmese versions are oily and onion-heavy; Malaysian and Indonesian curries include lemongrass, galangal, and shrimp paste. Even Vietnamese curries have their own twist with cilantro and scallions.

Curry in Africa and the West

Arab traders brought Indian spices to East Africa by the 8th century. In the 16th century, the Portuguese introduced the Tamil word “kaṟi” in Goa, spreading the term globally. British colonists later popularized curry across their empire, including in England, South Africa, and the Caribbean.

By the 18th century, curry powder was commercialized in Britain. Indian curry restaurants, like the one opened by Sake Deen Mahomed in 1809, began to flourish. Even Queen Victoria had Indian chefs preparing daily curry meals.

Japan’s Love for Curry

Brought to Japan by the British navy, Japanese curry adapted with flour thickeners and served with rice. It began in the military and quickly became one of the country’s most beloved comfort foods.

Biryani and Pilaf – Indian Roots with Persian Flair

The Ancient Rice Dish

The word “pilaf” comes from the Sanskrit word “pulāka.” Variants of rice cooked with meat are mentioned in the Mahabharata. When Persia conquered parts of India in the 5th century BCE, rice traveled westward.

From Persia to the World

Persian scholar Ibn Sina documented pilaf in the 10th century, calling it nutritious and restorative. The dish spread across the Middle East, Europe, and Asia—eventually returning to India and transforming into biryani.

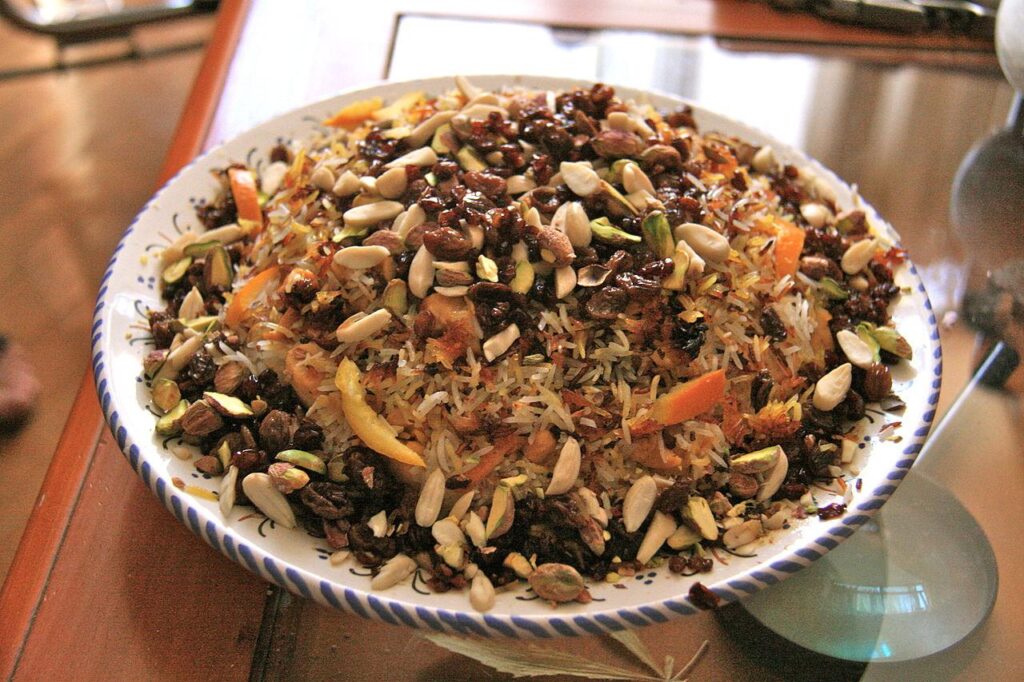

Biryani is usually richer and spicier than pilaf, cooked in layers with meat and fragrant rice. It comes in various regional styles—from Mughlai lamb biryani to coastal seafood versions.

Roti – India’s Flatbread Champion

Roti’s Rise to Fame

Roti, also called chapati, is India’s everyday unleavened bread, dating back to the Indus Valley civilization. Made from whole wheat flour, it’s simple, portable, and long-lasting—perfect for harsh climates.

Colonial soldiers, Indian laborers, and revolutionaries all relied on roti. During the 1857 Indian Rebellion, rotis were even used to send coded messages among freedom fighters. Today, roti has spread across the Caribbean, South Africa, and Southeast Asia.

Caribbean Roti Wraps

In Trinidad, Suriname, and Guyana, roti is often stuffed with curried meat, vegetables, or chickpeas—similar to a burrito. This fusion of convenience and flavor became a beloved street food.

Roti Canai – The Flying Bread of Southeast Asia

From Rumali Roti to Parotta

India’s rumali roti (“handkerchief bread”) is soft, thin, and often tossed in the air like pizza dough. Parotta, from South India, is a flaky, layered bread similar to Chinese scallion pancakes.

The Malaysian Twist

Indian Muslim migrants in Malaysia created roti canai, a hybrid of rumali roti and parotta. It’s now a staple across Malaysia, Indonesia, Singapore (as roti prata), and Thailand, served sweet or savory with curry, banana, or condensed milk.

Indian Pickles – Spicy, Sour, and Essential

Achar, the Ancient Preserver

Pickling in India dates back over 4,000 years. Achar includes mango, lime, garlic, and eggplant, often preserved in mustard or sesame oil with chili, tamarind, and garlic. Each region has its own favorite style.

Global Influence

Indian pickles inspired dishes like acar in Southeast Asia and piccalilli in the UK. British sailors used pickles to prevent scurvy, and cookbook author Hannah Glasse even included Indian pickle recipes in her 18th-century guides.

Ghee – India’s Golden Fat

Ghee, a form of clarified butter, comes from the Sanskrit word “ghṛuta” and has been part of Indian life for over 4,000 years. Sacred in Hinduism, it’s used in rituals, cooking, and traditional medicine.

It’s shelf-stable, rich in flavor, and lactose-free. Ayurveda praises it for aiding digestion and healing ulcers. Today, ghee is used in everything from lentil soups to sweets—and even in Tibetan butter tea.

Puttu – Steamed Coconut Rice Cakes

Puttu is a breakfast favorite in Kerala, made from rice flour, grated coconut, and salt. It’s steamed in bamboo cylinders and served with banana, palm sugar, or curry.

This dish traveled with Indian traders and laborers to Southeast Asia, evolving into kue putu and ondeh-ondeh in Indonesia and Malaysia—now festive treats often colored with pandan and filled with palm sugar.

One Cuisine, Countless Stories

From street stalls in Bangkok to royal banquets in London, Indian cuisine continues to influence and inspire. Whether you’re dipping roti into spicy curry or unwrapping a sweet banana roti in Thailand, you’re tasting thousands of years of history, migration, and flavor in every bite.