In recent years, Russian bread—particularly the infamous hard loaf known as Lieba—has found unexpected fame online. Thanks to viral humor posts dubbed Lieba literature, this dense and durable bread has become a meme-worthy icon. But behind its tough crust lies more than just laughs—it’s a cultural staple that represents the heart of Russian bread traditions.

What Exactly Is Lieba?

The term Lieba comes from the Russian word khleb (хлеб), simply meaning bread. Chinese people added the word “big” to describe its giant size and sturdy structure—thus, Da Lieba (Big Lieba).

Bread is more than food in Russia—it’s a lifeline. In the Soviet film Lenin in 1918, a famous line declares, “There will be bread. There will be everything.” It highlights how central bread is to Russian life.

Russian bread comes in many forms: round loaves, rings, locks, or long baguettes. But fundamentally, it divides into two kinds: black bread and white bread.

Black Bread: The Russian Staple

Black bread is made mostly from rye flour, which grows well in Russia’s harsh climate. This type of bread dates back to at least the 9th century, likely originating in Kievan Rus’. By the 17th century, tsarist records mentioned over 26 varieties of black bread.

Instead of yeast, black bread is traditionally fermented with hops. The dough often contains wheat germ, bran, and requires several days of fermentation and baking in a wood-fired oven. The result? A dark, shiny crust and a firm, chewy interior that doesn’t crumble easily.

Many find its sour and salty taste unfamiliar, but Russians love it. They eat it with soup, butter, caviar, cheese, jam—or even with vodka.

Even Russian nobility adored it. In 1836, Count Sheremetev wrote to poet Alexander Pushkin, complaining that life in Paris was unbearable without black bread.

Beyond Lieba: Russia’s Other Breads

The most elite Russian black bread is Borodinsky bread, said to have originated from a convent after the 1812 Battle of Borodino. Some claim it was created later in 1920s Moscow.

While black bread reigns supreme, white bread also has a place in Russian history. First baked in the 12th century, it was once a luxury item. Only the wealthy could afford bread made from refined white flour.

By the early 20th century, white bread became more accessible. Russians especially favor a type known as lock bread, a soft, slightly sweet loaf made from snowflake flour. Its origins trace back to Tatar influences.

Other notable Russian breads include:

- Krasnoselsky bread: Thin crust, rich aroma.

- Boyarsky bread from Moscow: A festive bread for weddings and celebrations.

- Starodubsky bread: Oval-shaped, often served with tea.

Why Is Lieba So Hard and Huge?

Chinese people often stereotype Russian bread as rock-hard and massive—and they’re not wrong.

Some Lieba loaves weigh over 2 kilograms. They have thick crusts that emit a loud knock when tapped. Fresh out of the oven, they’re soft inside—but after a day or two, moisture escapes and the bread becomes dense and tough.

Compared to soft, sweet Asian breads, Lieba feels dry and rough. It’s more functional than fancy. But Lieba isn’t alone—French baguettes and German sourdough are also notoriously tough.

Historically, European peasants baked bread in communal ovens, making giant loaves to last days or even weeks. As Les Misérables noted, French farmers sometimes had to soak bread in water for 24 hours just to eat it.

So the toughness wasn’t a flaw—it was survival.

Different Breads, Different Tastes

The divide between Asian and European bread reflects different culinary cultures. Europeans see bread as a staple food, pairing basic recipes (flour, water, yeast, salt) with cheese, ham, or pickles.

In contrast, most modern Chinese breads are influenced by Japanese-style baking, featuring soft dough enriched with milk, sugar, and eggs. Bread here is more dessert than dinner.

The Rise of the “Nutty Lieba”

A new star has emerged on Chinese social media: Nut Lieba, a modified version of traditional Lieba that originated in Xinjiang.

This long, rectangular loaf replaces water with milk and includes nuts, dried fruit, and honey. Unlike its Russian ancestor, Nut Lieba is moist, chewy, and sweet—closer in texture to fruitcake than rye bread.

Is it truly Russian? Kind of.

Russian Influence in China

Cities like Harbin and Yili have long-standing Russian connections. Harbin’s Russian-style bread dates back to 1898, when Russians came to build the Chinese Eastern Railway.

Even writer Xiao Hong mentioned surviving on black bread and salt during hard times in 1930s Harbin.

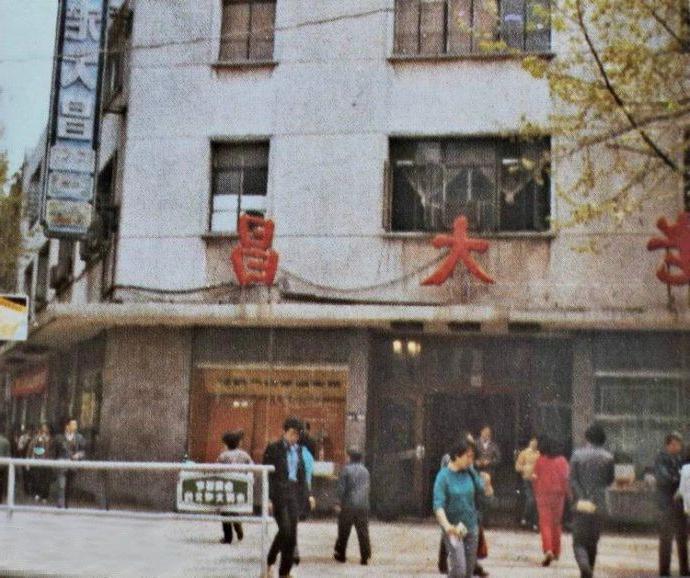

Today, Harbin’s Qiulin Lieba remains a popular souvenir—though it’s now made with wheat flour, not rye.

In Xinjiang, some ethnic Russian bakers still use hops fermentation and wood-fired ovens to bake traditional Lieba. But to suit modern Chinese tastes, local bakers adapted it into the sweet, nutty version we know today.

Russian Bread in Old Shanghai

In early 20th-century Shanghai, impoverished Russian refugees brought their breadmaking skills. Locals called their creations Luosong bread, derived from a mispronunciation of “Russia.”

Classic Luosong bread and Luosong stew became part of Shanghai’s culinary heritage. Legendary writer Eileen Chang fondly recalled a specific variant made by the bakery Old Dachang, describing it as subtly sweet and salty, topped with crispy crust and filled with cheese.

Final Thoughts

Whether it’s from Harbin, Xinjiang, or old Shanghai, Russian-style bread in China has been shaped and softened to suit local palates. It might not be 100% authentic—but it’s delicious.

After all, food doesn’t need to be traditional. It just needs to be good.