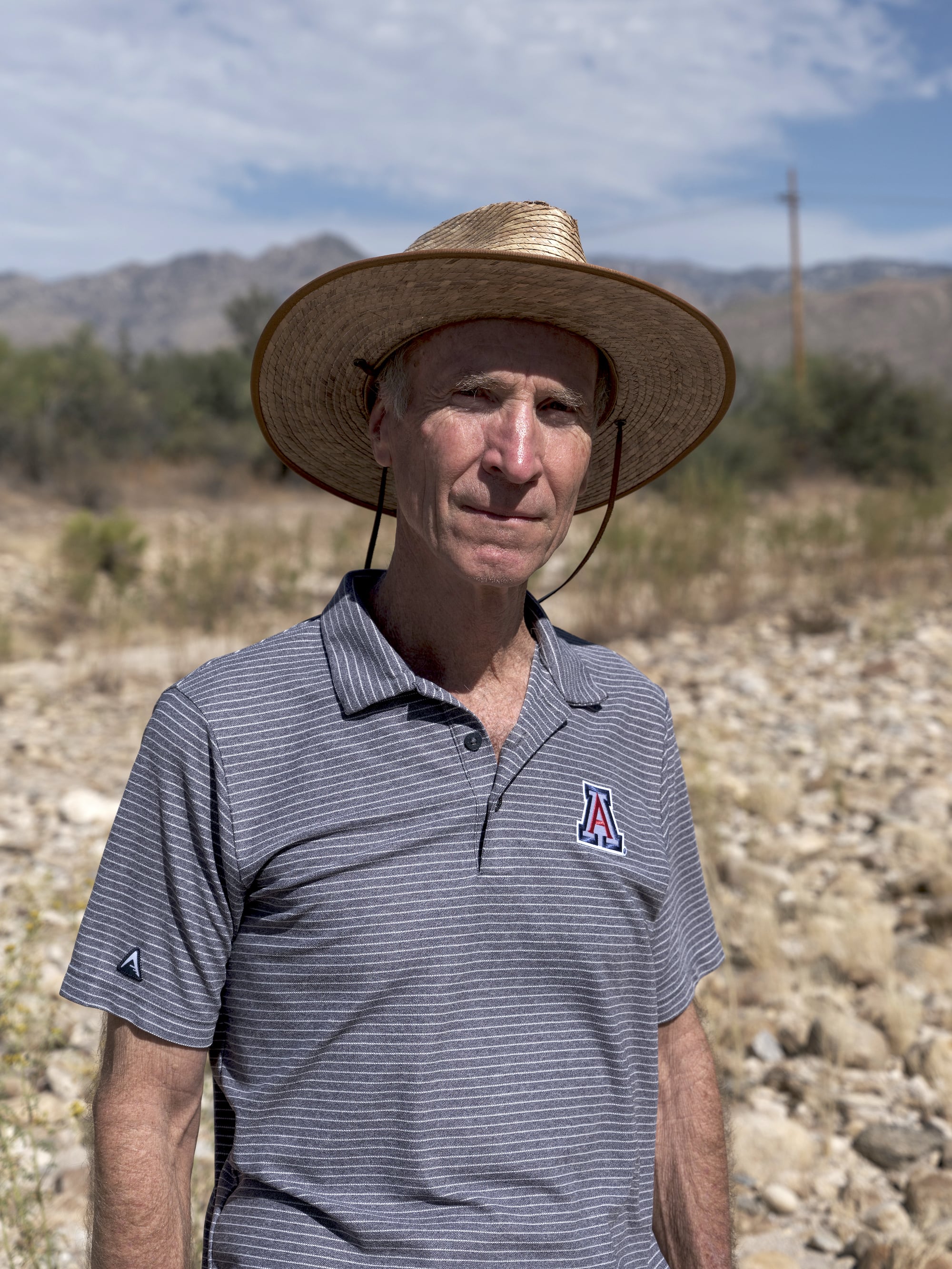

The morning temperature is nearing 100 levels Fahrenheit as Keith Seaman sweats beneath his bucket hat, strolling door to door via the cookie-cutter blocks of a subdivision in Casa Grande, Arizona. Seaman, a Democrat who represents this Republican-leaning space within the state’s Home of Representatives, is making an attempt to retain a seat he received by a margin of round 600 votes simply two years in the past. He desires to know what points matter most to his constituents, however most of them don’t reply the door, or they are saying they’re too busy to speak. Those who do reply have a tendency to say customary marketing campaign points like rising costs and training — which Seaman, a former public faculty instructor, is simply too pleased to debate.

“We’ll do our greatest to get extra public cash into training,” he tells one man within the neighborhood, earlier than turning to the constituent’s kindergarten-age daughter to pat her on the pinnacle. “What grade are you in?”

“Why are you at our home?” the woman asks in return.

Seaman has knocked on 1000’s of doorways as he seeks reelection this 12 months. Whereas his voters are fired up about all the things from inflation to abortion, one difficulty doesn’t come up a lot on Seaman’s scorching tour via suburbia — though it’s plainly seen within the parched cotton and alfalfa fields that encompass the subdivision the place he’s stumping for votes.

That difficulty is water. In Pinal County, which Seaman represents, water shortages imply that farmers not have entry to the Colorado River, previously the lifeblood of their cotton and alfalfa empires. The booming inhabitants of the realm’s subdivisions face a water reckoning as properly: The state has positioned a moratorium on new housing growth in elements of the county, as a part of an effort to guard dwindling groundwater assets.

Over the previous 4 years, Arizona has turn out to be a poster little one for water shortage in america. Between a long time of unsustainable groundwater pumping and a once-in-a-millenium drought, fueled by local weather change, water sources in each area of the state are underneath risk. As groundwater aquifers dry up close to a few of the most populous areas, officers have blocked 1000’s of recent properties from being in-built and across the booming Phoenix metropolitan space. In additional distant elements of the state, water-guzzling dairy farms have brought about native residents’ wells to run dry. The drought on the Colorado River, lengthy a lifeline for each agriculture and suburbia throughout the U.S. West, has pressured additional water cuts to each farms and neighborhoods within the coronary heart of the state.

Arizona voters know that they’re deciding the nation’s future — the state is certainly one of only a half-dozen prone to decide the following president — however it’s unclear in the event that they know that they’re voting on an existential risk in their very own backyards. The end result of state legislative races in swing districts like Seaman’s will decide who controls the divided state legislature, the place Democrats are selling new water restrictions and Republicans are combating to guard thirsty industries like actual property and agriculture, no matter what meaning for future water availability.

“All people’s working for re-election,” mentioned Kathleen Ferris, who crafted a few of the state’s landmark water laws and now teaches water coverage at Arizona State College. “No one desires to sit down across the desk and attempt to cope with these points.”

For these lawmakers’ voters, subjects like abortion, the financial system, and public security are drawing way more consideration than the water of their faucets, and will probably be these points that drive the most individuals to the polls. However for the state officers who win on election day, their most consequential legacy could be what they resolve to do about the way forward for water in Arizona.

“They hold saying, ‘properly, water is nonpartisan,’” Ferris added. “That’s not true anymore. It’s actually not true.”

Eliseu Cavalcante / Grist

It’s not onerous to see why hot-button points like immigration and the price of dwelling are on the minds of Arizona voters: The state sits on the U.S.-Mexico border and has skilled a few of the highest charges of inflation within the nation over the previous few years. In the meantime, its Republican-controlled state legislature has minimize public training funding and allowed a nineteenth-century abortion ban to stay in impact after the Supreme Court docket overturned Roe v. Wade. The state is on the heart of virtually each main political debate — “the middle of the political universe,” in Politico’s phrases — and its practically evenly divided citizens makes its swing votes key to figuring out who controls each the White Home and Congress.

Even when the temperature doesn’t prime 115 levels F, the ensuing marketing campaign frenzy could make an out-of-state customer light-headed. Garden indicators muddle fuel station parking tons, freeway medians, and entrance yards; nearly each different tv industrial is an advert for or towards a candidate for Congress, the presidency, or some state workplace. A industrial slamming a Democratic candidate as a defund-the-police radical will incessantly air proper after an advert condemning a Republican as a risk to democracy itself. Mailers and marketing campaign literature clog mailboxes and dangle on doorknobs.

This avalanche of marketing campaign promoting seldom mentions water. Throughout every week reporting within the state, I noticed precisely one advert that targeted on the difficulty. It was a billboard in Tucson asserting that Kirsten Engel, the Democratic candidate for a pivotal congressional seat, helps “Defending Arizona from Drought” — not precisely a substantive engagement with the difficulty.

The explanation for this avoidance is straightforward, in response to Nick Ponder, a vice chairman of presidency affairs at HighGround, a number one Arizona political technique agency. He mentioned that whereas many citizens within the state rank water amongst their prime three or 4 points, most don’t have an in depth understanding of water coverage — that means it’s unlikely that they’ll vote based mostly on how candidates say they’ll deal with water points.

“They perceive that we’re in a desert, and that we now have water challenges — specifically groundwater and the Colorado River — however I don’t assume that they perceive learn how to greatest handle that,” he informed Grist.

Eliseu Cavalcante / Grist

And the way might they? Understanding Arizona water coverage entails a maze of acronyms — AMA, GMA, INA, ADWR, CAWS, DAWS, DCP, CAP, and CAGRD are simply the entry-level nouns — and complicated technical fashions that observe water ranges 1000’s of ft underground. Even many elected officers on each side of the aisle aren’t properly versed within the difficulty, in order that they defer to the social gathering leaders who’ve the strongest grasp on how the state’s water system works.

One upshot of this confusion — in addition to the state’s bitter partisan divide — is that, whilst Arizona’s water disaster has gained nationwide consideration, state lawmakers have didn’t cross vital laws to deal with the deficit of this crucial useful resource. Over the previous two years, the state’s Democratic governor, Katie Hobbs, has been unable to dealer a cope with the Republicans who management each chambers of the state legislature. Hobbs has put ahead a sequence of proposals that may reform each agricultural water use in rural areas and fast growth within the suburbs of Phoenix, however she has come up a handful of votes in need of passing them. Republicans have put ahead their very own plans — that are friendlier to the avowed water wants of farmers and housing builders — that she has vetoed.

As soon as you chop via the thicket of studies and acronyms, it’s clear that this 12 months’s election is pivotal for breaking this gridlock and figuring out the way forward for water coverage within the state. Republicans maintain one-vote majorities in each chambers of the legislature, so state Democrats solely must flip one seat in every chamber so as to achieve unified management of the federal government. If that occurs, Hobbs will have the ability to ignore the objections of the agriculture and homebuilding industries, which have stored Republicans from signing on to her plans.

Hobbs and the Democrats wish to restrict or prohibit new farmland in rural areas, whereas concurrently making it more durable for homebuilders round Phoenix and Casa Grande to renew constructing new subdivisions. This might decelerate, however not reverse, the decline in water ranges across the state — and it will probably diminish income for 2 industries which can be pillars of the state’s financial system. If Republicans retain management of the legislature, they might reopen new suburban growth and roll out extra versatile guidelines for rural groundwater, giving a freer hand to each industries however incurring the chance of extra groundwater shortages in a long time to return.

Legislators got here near reaching settlement on each points earlier this 12 months. Republicans handed a invoice that may loosen up growth restrictions on fallow farmland the place housing tracts could possibly be developed — a compromise with theoretical enchantment to each events’ need to maintain constructing housing for the state’s booming inhabitants — however Hobbs vetoed it, saying it lacked sufficient safeguards to stop future water shortages. On the identical time, lawmakers from each events made progress on a deal that may permit the state to set limits on groundwater drainage in rural areas, however the talks stalled as this 12 months’s legislative session got here to a detailed.

“We had so many conferences, and we’ve by no means gotten nearer,” mentioned Priya Sundareshan, a Democratic state senator who’s the social gathering’s foremost knowledgeable on water points within the legislature. “Now we’re in marketing campaign mode.”

In Seaman’s district of Pinal County, the place water restrictions have created difficulties for each the agriculture and actual property industries, lots of those that are engaged on water points see a stark partisan divide. Paul Keeling, a fifth-generation farmer in Casa Grande, framed the scarcity of water on the Colorado River as a contest between pink Arizona and blue California.

“We’re supposed to have the ability to get part of that water, and now we will’t,” he informed Grist. “It’s all going to California, to the f***ing liberals and the Democrats.”

Keeling has needed to shrink his household’s cotton-farming enterprise over the previous few years, as a result of he’s misplaced the fitting to attract water from the canal that delivers Colorado River water to Arizona. It’s one motive amongst many who Keeling mentioned he’s supporting former President Donald Trump this 12 months, as he has up to now two elections.

The Republican management of Pinal County has sparred with Governor Hobbs and state Democrats on housing points as properly, albeit in far much less animated phrases. In response to research exhibiting the county’s aquifer diminishing, the state authorities positioned a moratorium on new groundwater-fed growth within the space in 2019. Homebuilders and builders pinned their hopes on Republicans’ proposed reform permitting new growth on former farmland, however Hobbs’s veto dashed these goals.

Stephen Miller, a conservative Republican who serves on the county’s board of supervisors, informed Grist that he views the Democrats’ opposition to new Pinal County growth as motivated by partisan politics. The Republicans legislators who signify the realm voted in favor of the invoice that may restart growth, however Seaman, the realm’s lone Democratic consultant, voted towards it.

“We’re simply sitting again watching as a result of the make-up of the Home and the Senate will decide what occurs right here,” Miller mentioned. “In the event that they’re each taken over by the Democrats, I believe there’s most likely little or no we will do [to relax the development restrictions].”

As Miller sees it, the restriction on new housing is a part of a ploy by the state’s Democratic institution to suppress progress in a conservative space — and even repossess its water.

“It shouldn’t be a partisan factor in any respect,” he mentioned. “You’d assume that they’d all wish to pull this wagon in the identical route. However all they need Pinal County for is to stay a straw in right here and take our water.”

One more reason for the relative marketing campaign silence on water points is that the areas the place water is most threatened — areas the place huge agricultural groundwater utilization has emptied family wells and brought about land to crack aside — are typically represented by the politicians who’re most dismissive of water conservation efforts, and vice versa. Cochise County, the place an unlimited dairy operation known as Riverview has residents up in arms over vanishing properly water, backed Trump by virtually 20 factors in 2020; La Paz County, the place an enormous Saudi farming operation has drained native aquifers, backed the previous president by virtually 40 factors. The state representatives from these areas are virtually all Republicans against new water regulation; many have direct ties to the agriculture or actual property industries.

In the meantime, nearly all of pro-regulation Democrats within the state legislature signify city areas which have extra numerous sources of water, stronger laws, and extra backup water to assist them get via intervals of scarcity.

The state legislature’s two main voices on water exemplify this divide. Democratic state senator Priya Sundareshan represents a progressive district within the core of Tucson, the place metropolis leaders have banked trillions of gallons of Colorado River water, all however guaranteeing that town received’t go dry — and may even proceed to develop because the river shrinks.

Sundareshan’s chief adversary is Republican Gail Griffin, a veteran legislator from Cochise County who chairs the decrease chamber’s highly effective pure assets committee. Griffin, a realtor, has blocked practically all proposed water laws for years, stopping even payments from members of her personal social gathering from getting a vote. Different legislators and water consultants usually cite her because the principal motive the state has not moved any main payments to manage rural water utilization — though the county she represents faces arguably probably the most acute water disaster of all of them. (Griffin didn’t reply to Grist’s requests for remark.)

Sundareshan, for her half, admits that it’s awkward that city legislators try to set water coverage for the agricultural elements of the state. However she says that Republicans have stalled on the difficulty for too lengthy.

“It doesn’t look nice,” she mentioned. “However proper now, rural legislators are setting coverage for city areas. That’s why that’s why legislators like me are stepping as much as say, ‘properly, we have to truly clear up these points.’ Water is water, proper? And the shortage of availability of water in a rural space goes to influence the provision of water in our city areas.”

The backlash to unsustainable groundwater pumping isn’t just coming from city progressives, although — it’s additionally coming rural Republicans’ personal constituents. In 2022, Cochise County voters accepted a poll proposal to limit the expansion of their water utilization. (The strictness of the brand new guidelines continues to be being debated.) Even so, there’s no signal that any of those areas will endorse a Democrat. When Hobbs held a sequence of city halls in rural areas dealing with groundwater points final 12 months, she and her workers confronted vital blowback from attendees who didn’t need the state meddling of their water utilization. This 12 months, elections in these areas aren’t even near aggressive. Griffin, the legislature’s strongest opponent of water regulation, is working unopposed.

Because of this the way forward for the state’s water coverage depends upon voters in only a few swing districts that straddle the urban-rural divide: suburban seats on the outskirts of Phoenix and Tucson, the place new subdivisions collide with vestigial farmland and open desert. For a lot of voters in these purple districts, Arizona’s water issues are removed from a motivating political difficulty — and sure received’t be for many years to return, as aquifers silently diminish underground. Voters may hear about water points in different elements of the state, or wince after they see their water payments, however the disappearing water underneath their ft is all however invisible, and will stay so for the remainder of their lives.

This dissonance is greatest exemplified by the seventeenth state legislative district, maybe probably the most pivotal swing seat within the legislature. The district extends alongside the northern fringe of Tucson, roping in a mixture of retirement communities, rural homes, and cotton farms which will quickly get replaced by new tract housing. Lots of the new developments in these areas, such because the sprawling Saddlebrooke neighborhood, depend on finite aquifers and get water delivered by personal firms. To adjust to Arizona legislation, builders need to show that they’ve sufficient water to provide new properties for 100 years, however even that doesn’t assure that the aquifers received’t proceed drying up.

Eliseu Cavalcante / Grist

It’s tough to curiosity voters in a groundwater decline that’s taking place out of view, in a disaster that nearly no person is speaking about publicly. The very best that native Democrats can do is make a common pitch that water safety isa frequent sense, bipartisan downside that they’re dedicated to fixing — while not having to clarify how they might resolve advanced questions concerning the interaction between water regulation and financial progress, amongst different nuances.

John McLean, a former engineer who’s working towards a longtime conservative legislator in an effort to flip the seventeenth district, has sought to place himself as a straight-down-the-middle average. His marketing campaign literature doesn’t point out his social gathering affiliation, however it does tout water as certainly one of his three key coverage points, together with public training and abortion entry. The marketing campaign pamphlet he’s been leaving within the doorways of properties in Saddlebrooke argues for a “commonsense approaches to safe our water future” and declares that “we should cease overseas and out-of-state firms from pumping limitless water out of our state” — one thing that has occurred within the conservative, rural elements of Arizona, however nowhere close to Saddlebrooke and the seventeenth district.

Eliseu Cavalcante / Grist

After I joined him as he knocked doorways in Saddlebrooke, McLean informed me that he’s discovered that nearly each voter he meets agrees with him on the necessity for wise water laws — a far cry from lightning-rod points like public security, abortion, and inflation.

“All people is de facto critical about water independence, and I believe that they’re involved about partisanship,” he mentioned. “I don’t assume there’s actually a lot of a partisan distinction amongst residents relating to water.”

That obvious consensus, nevertheless, doesn’t lengthen to the state’s elected officers.

“My Republican opponent voted to loosen up groundwater pumping restrictions,” McLean, referring to a invoice that may have eradicated authorized legal responsibility for groundwater customers whose water utilization compromised close by rivers or streams. “So he was on precisely the fallacious facet of that one.”