A New Kind of Contraband

As night falls over Ciudad Juárez, a city notorious for its borderland struggles, an unexpected item has risen to underground fame—Krispy Kreme donuts. Forget drugs and counterfeit goods; the real prize here is a box of perfectly glazed, melt-in-your-mouth donuts smuggled straight from the United States.

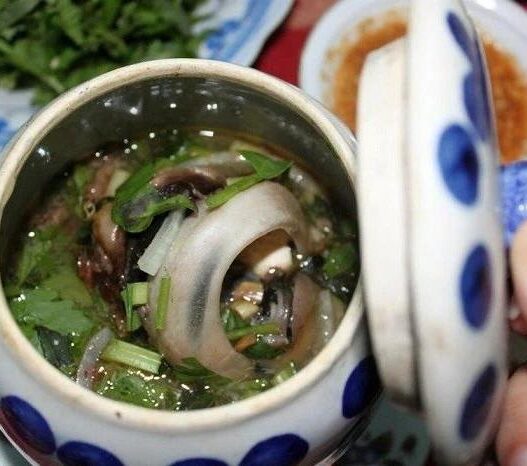

“Classic glaze, rich filling, and just the right fluff—these are the gold standard,” says Celesto, a street vendor known for his late-night donut drops.

Juárez has donuts, but not Krispy Kreme. Local pastries, often greasy and bland, pale in comparison. As one resident puts it:

“Call them churros, fried bread, or sugar cakes, but don’t call them donuts—unless you want the Guzmán family knocking on your door.”

Why Krispy Kreme?

Founded in 1937, Krispy Kreme has become one of the world’s most beloved donut brands, known for its pillowy texture and indulgent glazes. When the company entered the Mexican market in 2004, it instantly won the hearts of locals.

Even today, Krispy Kreme remains Mexico’s ultimate gift. Travelers flying from Mexico City to rural areas often bring a box as a peace offering. Forgetting to do so could result in a mother-in-law’s chili-laced revenge.

But while most Mexican cities enjoy access to Krispy Kreme through its 100+ official stores, Juárez is an exception. Constant gang violence and cartel activity forced the local Krispy Kreme outlet to close, leaving donut lovers stranded.

From Sweet Cravings to Underground Hustle

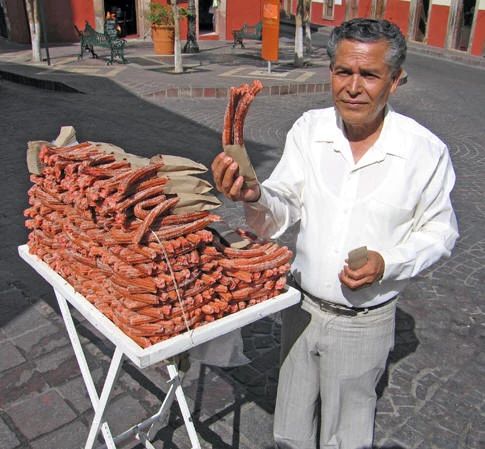

51-year-old Sonia García, dubbed the “Donut Queen,” runs one of the most successful cross-border Krispy Kreme operations in Juárez. Every week, her son crosses into El Paso, Texas to visit the nearest Krispy Kreme store. He buys around 40 boxes of the classic glazed donuts, paying $5 per dozen.

Back in Juárez, García and her other son sell the donuts at a 60% markup, advertising pop-up locations an hour before each sale. The demand? Insatiable.

“The moment we arrive, locals—some looking suspiciously like addicts—swarm the trunk, desperate for their fix,” García laughs. “For big orders, we even wear bulletproof vests for home deliveries.”

Their booming business earned them the nickname “Krispy Kreme Familia”—a playful nod to the infamous La Familia Michoacana cartel. The name not only deters would-be thieves but also makes it clear: they deal strictly in donuts, not drugs.

“These donuts helped pay for my son’s engineering degree,” García proudly adds.

From Narco Routes to Donut Runs

Not every border resident has a special work visa, but García’s family is among the thousands legally permitted to cross into the U.S. regularly. Others, like Alejandro, a former drug mule, have found the donut trade a safer alternative.

“My SUV can hold around 150 boxes—that’s $600 per trip,” Alejandro explains. “Low risk, stable customers, and no need for bribes. If I’m stopped, I’m just a guy with great taste in snacks.”

The cross-border donut trade has become so normalized that locals joke: “For every ten donuts made in El Paso, one Juárez gangster gets closer to diabetes.”

The Black Market Spreads North

But the smuggling trend isn’t limited to Mexico. In Minnesota, Krispy Kreme had been absent for over 11 years, much to the dismay of local donut lovers. That is, until 21-year-old accounting student Jason Gonzalez emerged as an unlikely hero.

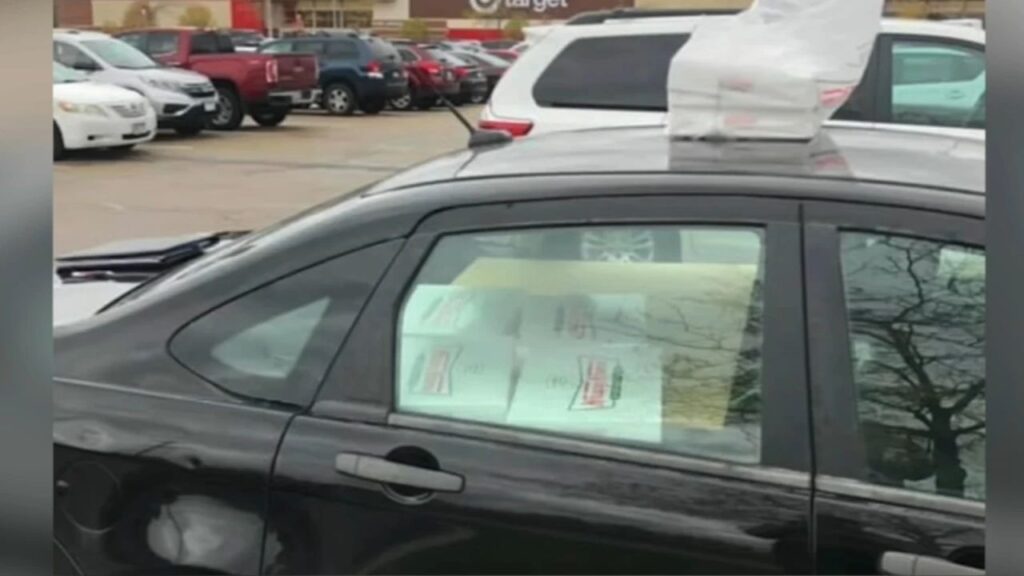

Nicknamed the “Donut Savior,” Gonzalez drove 270 miles (about 8 hours round trip) from Minnesota to Clive, Iowa, the nearest Krispy Kreme location. Each trip, he packed his Ford Focus with 100 boxes and sold them for $17 to $20 per box—more than double the original price.

“Who doesn’t love Krispy Kreme?” says regular customer Katherine Newton, who buys two to three boxes per drop. Even the local sheriff, after indulging, couldn’t resist joking:

“These donuts are criminally delicious.”

Sweet Success, Bigger Dreams

Encouraged by his success, Gonzalez launched a GoFundMe campaign, aiming to raise $20,000 for a larger vehicle.

“Ideally, I’d buy a used van or truck, boosting capacity to 200-300 boxes per trip,” he shared.

As reported by the Los Angeles Times, donut smuggling is becoming a cross-border phenomenon. From El Paso to Minnesota, the allure of Krispy Kreme is fueling an underground economy driven not by desperation, but by pure, sugary delight.

“It’s a business,” Gonzalez shrugs. “So far, the only downside is eating too many donuts myself. But hey, at least my customers are happier than I am—and more likely to hit the treadmill.”