When John Holbrook first began working as a pipefitter within the early Nineties, jobs had been straightforward to return by in his nook of northeastern Kentucky.

An enormous iron and metal mill routinely wanted upkeep and restore work, as did the coal “coking” ovens subsequent to it. There was additionally a hulking coal-fired energy plant and a bustling petroleum refinery close by. Fossil fuels extracted from beneath the area’s rugged Appalachian terrain equipped these industrial websites, which sprung up in the course of the nineteenth and twentieth centuries alongside the yawning Ohio River and its tributary, Massive Sandy.

“Work was so plentiful,” Holbrook recalled on a scorching August morning in Ashland, a quiet riverfront metropolis of some 21,000 folks.

Ashland retains its motto because the place “The place Coal Meets Iron,” and railcars nonetheless rumble by. However after years of downsizing manufacturing, the metal mill’s proprietor demolished the complicated in 2022. A decade in the past, the coal plant switched to burning pure gasoline to generate electrical energy, which requires much less hands-on upkeep. In the meantime, 1000’s of jobs vanished from surrounding coalfields as mining turned extra mechanized, market forces shifted, and clear air insurance policies took maintain.

Many households have since moved away. The tradespeople who’ve stayed usually drive for hours to work on the brand new development initiatives sprouting up elsewhere, like the huge factories for making and recycling electric-car batteries in western Kentucky and the electricity-powered metal furnace in neighboring West Virginia. If America is present process a manufacturing growth, it hasn’t but reached this hard-hit stretch of the Bluegrass State.

However that would quickly change.

In March, Century Aluminum, the nation’s greatest producer of main, or virgin, aluminum, introduced that it plans to construct an infinite plant in the USA — the nation’s first new smelter in 45 years. Jesse Gary, the corporate’s president and CEO, has pointed to northeastern Kentucky because the mission’s most popular location, although he mentioned there have been nonetheless a “myriad of steps” earlier than the corporate reaches a ultimate resolution.

The Chicago-based producer is slated to obtain as much as $500 million in funding from the U.S. Division of Power to construct the ability, which might emit 75 % much less carbon dioxide than conventional smelters, due to its use of carbon-free vitality and energy-efficient designs. The award is a part of a $6.3 billion federal program — funded by the Inflation Discount Act and the Bipartisan Infrastructure Regulation — that goals to sharply scale back greenhouse gasoline emissions from heavy-industry sectors.

The Ohio River seen from Ashland, Kentucky, proper. John Holbrook at his workplace in Ashland.

Aluminum demand is about to soar globally by as much as 80 % by 2050 because the world produces extra photo voltaic panels and different clear vitality applied sciences. The makers of the important materials are actually below mounting stress from policymakers and shoppers to scrub up their operations. In North America alone, aluminum producers might want to minimize carbon emissions by 92 % from 2021 ranges to satisfy net-zero local weather objectives.

Century already owns two ageing smelters in western Kentucky. The brand new “inexperienced smelter” is predicted to create over 5,500 development jobs and greater than 1,000 full-time union jobs. If in-built jap Kentucky, the $5 billion mission would mark the area’s largest funding on file.

“We simply want a crumb or two, only a little large smelter,” Holbrook mentioned with a giggle once we met at his workplace close to Ashland’s historic fundamental avenue. A brief stroll away, stones used within the metropolis’s authentic iron-making furnaces stand as monuments overlooking the Ohio River.

At the moment, Holbrook heads the Tri-State Constructing and Development Trades Council, which represents unions in a cluster of adjoining counties in Kentucky, Ohio, and West Virginia. He’s a part of a broad coalition of labor organizers, native officers, environmentalists, and clear vitality advocates who’re urging Kentucky Governor Andy Beshear, a Democrat, to work with Century to safe the smelter and hammer out a long-term deal to offer clear vitality for it.

“It’d be a godsend for that space,” mentioned Chad Mills, a pipefitter and the director of the Kentucky State Constructing and Development Trades Council. The area “wants it greater than you may think about.”

The impression of Century’s new smelter would ripple far past this rural stretch of verdant peaks and meandering creeks.

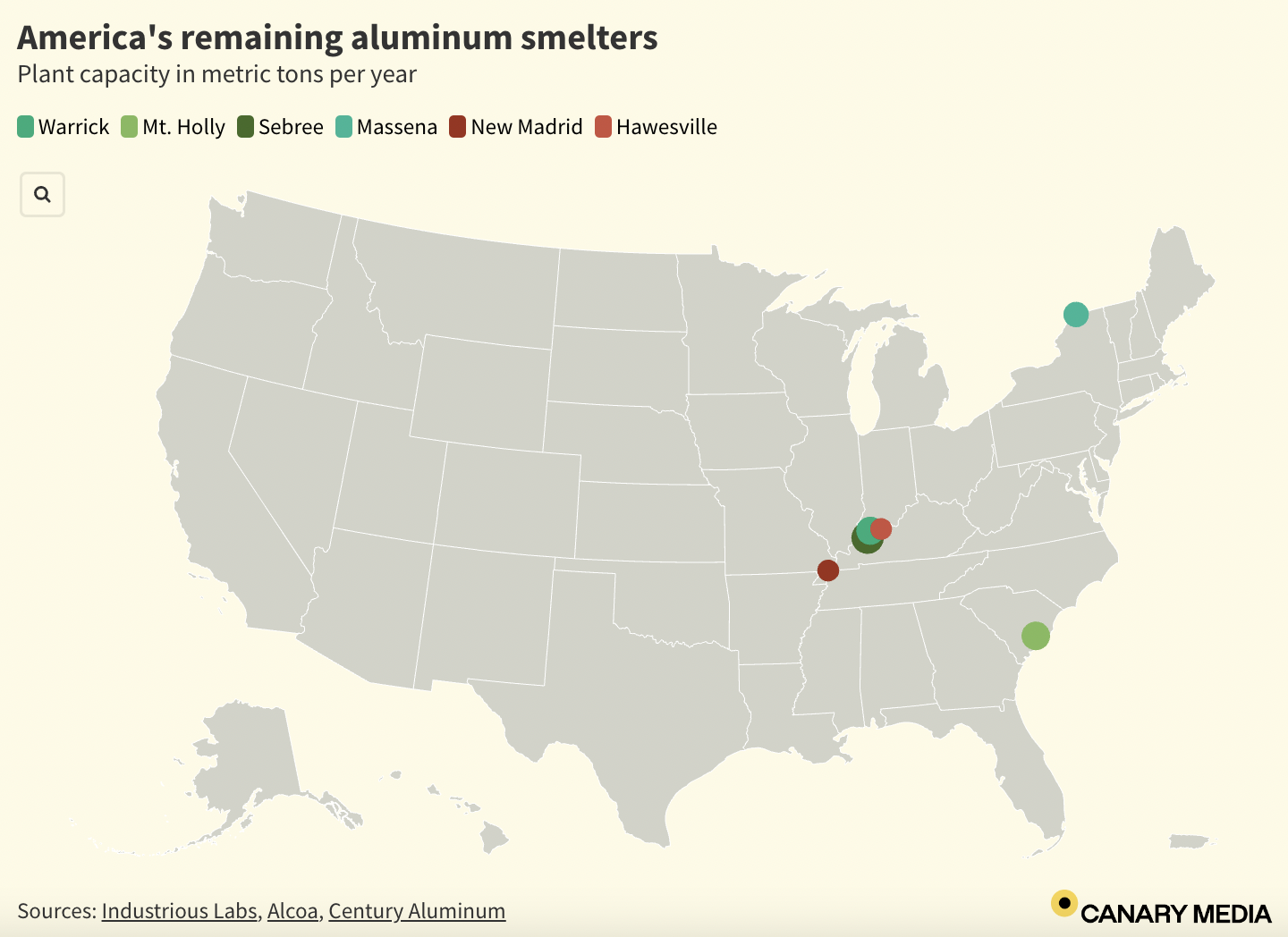

The deliberate facility is about to almost double the quantity of main aluminum that the USA produces — serving to to revitalize a home {industry} that has been steadily shrinking for many years owing to spiking energy costs and elevated competitors from China. In 2000, U.S. corporations operated 23 aluminum smelters. At the moment, solely 4 crops are working, whereas one other two have been indefinitely curtailed. That features Century’s 55-year-old plant in Hawesville, Kentucky, which has been idle since June 2022.

The decline in U.S. manufacturing has sophisticated the nation’s efforts to each make and procure lower-carbon aluminum for its provide chains, specialists say.

Globally, the aluminum sector contributes round 2 % of complete greenhouse gasoline emissions yearly. Practically 70 % of these emissions come from producing excessive volumes of electrical energy — usually derived from fossil fuels — to energy smelters nearly across the clock.

As U.S. main manufacturing dwindles, the nation is importing extra aluminum made in abroad smelters which are powered by dirtier, much less environment friendly electrical grids. Paradoxically, an growing share of that aluminum is getting used to make photo voltaic panels, electrical automobiles, warmth pumps, energy cables, and plenty of different clear vitality elements. The metallic is light-weight and cheap, and it’s a key ingredient in international efforts to impress and decarbonize the broader economic system.

However aluminum can also be mind-bogglingly ubiquitous outdoors the vitality sector. The versatile materials is present in every little thing from pots and pans, deodorant, and smartphones to automobile doorways, bridges, and skyscrapers. It’s the second-most-used metallic on the earth after metal.

Final 12 months, the U.S. produced round 750,000 metric tons of main aluminum whereas importing 4.8 million metric tons of it, in line with the U.S. Geological Survey.

In the meantime, the nation produced 3.3 million metric tons of “secondary” aluminum in 2023. Boosting recycling charges is seen as a obligatory step for addressing aluminum’s emissions downside, as a result of the recycling course of requires about 95 % much less vitality than making aluminum from scratch. However even secondary producers want main aluminum to “sweeten” their batches and obtain the fitting energy and sturdiness, mentioned Annie Sartor, the aluminum marketing campaign director for Industrious Labs, an advocacy group.

“Major aluminum is crucial, and we now have a main {industry} that’s been in decline, could be very polluting, and could be very high-emitting,” Sartor mentioned. Century’s proposed new smelter “might be a turning level for this {industry},” she added. “All of us wish to see it get constructed and thrive.”

Luke Sharrett for The Washington Put up by way of Getty Pictures

A brand new inexperienced smelter wouldn’t simply enhance provides of main aluminum for making clear vitality applied sciences. The ability, with its voracious electrical energy urge for food, can also be anticipated to speed up the area’s buildout of unpolluted vitality capability, which has lagged behind that of many different states.

Century expects its deliberate smelter to provide about 600,000 metric tons of aluminum a 12 months. Which means it may need a minimum of a gigawatt’s value of energy to function yearly at full tilt, equal to the yearly demand of roughly 750,000 U.S. houses. By means of comparability, Louisville, Kentucky’s largest metropolis, is residence to some 625,000 folks.

However Kentucky has little or no carbon-free capability accessible right this moment.

About 0.2 % of the state’s electrical energy era got here from photo voltaic in 2022, whereas 6 % was equipped by hydroelectric dams, primarily within the western a part of the state. Coal and gasoline crops produced a lot of the relaxation. Nonetheless, after a long time of clinging tightly to its coal-rich historical past, Kentucky is seeing a raft of latest utility-scale photo voltaic installations below growth, together with atop former coal mines.

And producers in Kentucky can entry the renewable vitality being generated in neighboring states in addition to regional grid networks like PJM. Swaths of jap Kentucky are coated by a strong array of high-voltage, long-distance transmission traces operated by Kentucky Energy, a subsidiary of the utility large American Electrical Energy.

Lane Boldman, government director of the Kentucky Conservation Committee, mentioned that investing in clear vitality and upgrading grid infrastructure would supply a likelihood to make use of extra of Kentucky’s expert staff.

“It’s thrilling, as a result of it truly modernizes our {industry} and leverages a native workforce that has a nice experience with vitality already,” she mentioned once we met in Lexington, close to the rolling inexperienced hills and lengthy white fences of the realm’s horse farms. “There are methods you may create financial growth that aren’t so extractive, that simply depart the neighborhood naked.”

Maria Gallucci/Canary Media

Northeastern Kentucky isn’t the one location that Century is contemplating for the smelter. The corporate can also be evaluating websites within the Ohio and Mississippi river basins. The ultimate resolution will depend upon the place there’s a regular provide of inexpensive energy, a Century government informed The Wall Road Journal in early July. (A spokesperson didn’t reply to Canary’s repeated requests for remark.)

Century is aiming to safe a power-supply deal to satisfy a decade’s value of electrical energy demand from the brand new smelter, in line with the Journal. The objective is to finalize plans within the subsequent two years after which start development, which might take round three years. Within the meantime, the U.S. will proceed to see a speedy buildout of photo voltaic, wind, and different carbon-free energy provides connecting to the grid.

Governor Beshear has participated in discussions concerning the smelter’s energy provide, within the hopes of touchdown Century’s megaproject and all of its “good-paying jobs.” His administration “continues to work with a number of specialists to find out a location in northeastern Kentucky that features a river port and may assist workforce coaching in addition to present the cleanest, most dependable electrical service capability wanted,” Crystal Staley, a spokesperson for the governor’s workplace, mentioned by electronic mail.

Environmental advocates say the aluminum plant represents a likelihood to reimagine what a main industrial facility can appear like: powered by clear vitality, outfitted with fashionable air pollution controls, and constructed with local people enter from the start. Beginning someday this fall, the Sierra Membership is planning to host public conferences and distribute flyers in northeastern Kentucky to let residents know concerning the large smelter that would doubtlessly be constructed of their backyards.

“It’s a chance for us to interact individuals who would possibly draw back from different features of being an environmental activist and say, ‘Hey, that is one thing that we will embrace, as a result of it’s going to assist us create jobs so that folks can keep of their area,’” mentioned Julia Finch, the director of Sierra Membership’s Kentucky chapter. “It is a likelihood for us to guide on what a inexperienced transition seems to be like for {industry}.”

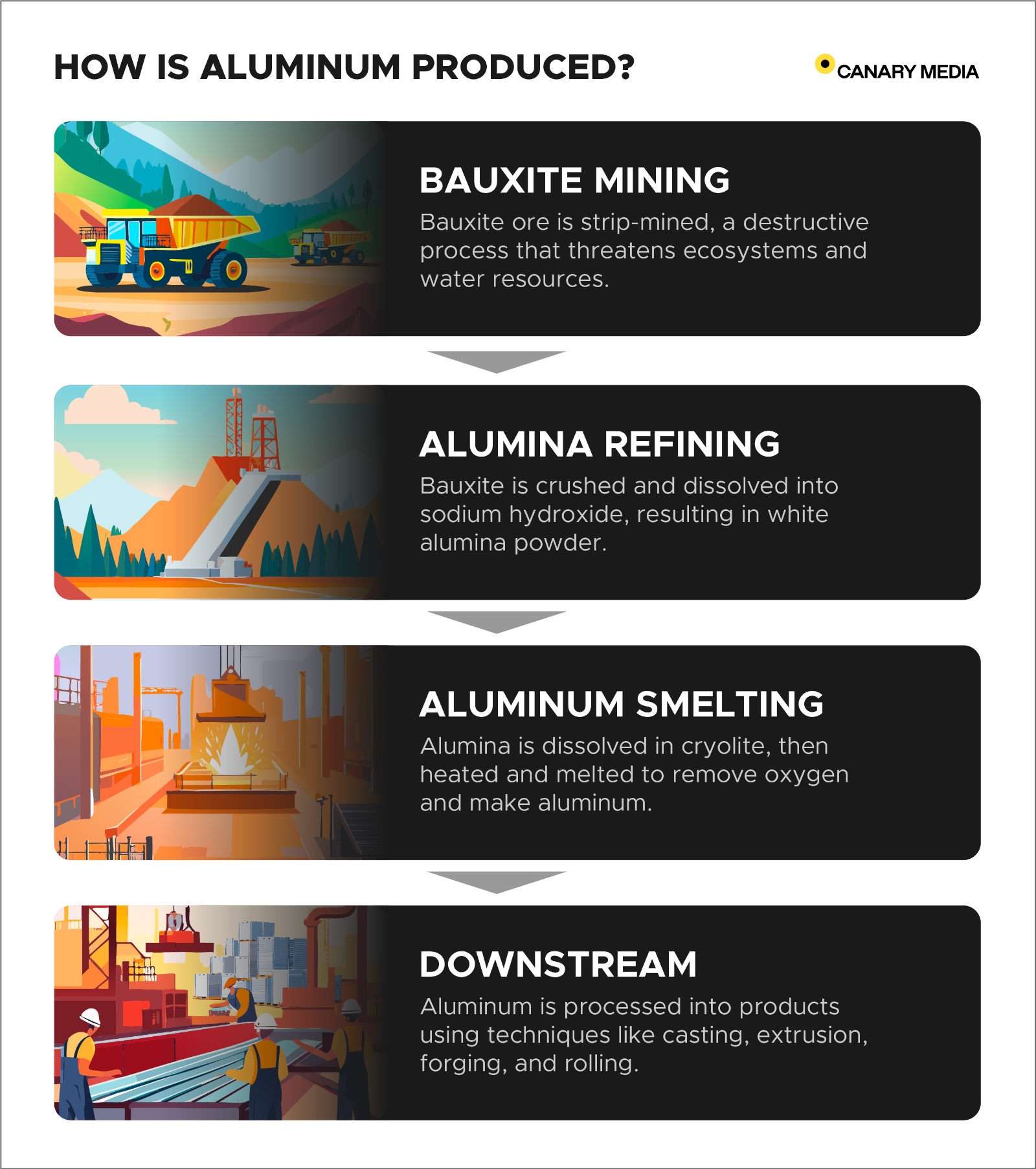

Aluminum is essentially the most considerable metallic in Earth’s crust. However turning it right into a sturdy, usable materials is a laborious and soiled course of — one which begins with scraping topsoil to extract bauxite, a reddish clay rock that’s wealthy in alumina (additionally referred to as aluminum oxide). The trickiest half comes subsequent: eradicating oxygen and different molecules to remodel that alumina into aluminum. Till the late nineteenth century, the strategies for engaging in this had been so expensive that the tinfoil we now purchase on the grocery retailer was thought-about a treasured metallic, like gold, silver, and platinum.

Then in 1886, Charles Martin Corridor found out a cheap approach to smelt aluminum by electrolysis, a method that makes use of electrical vitality to drive a chemical response. Not lengthy after, he helped launch the Pittsburgh Discount Firm, which went on to turn into the U.S. aluminum behemoth presently referred to as Alcoa.

Across the identical time that Corridor was tinkering in his woodshed in Oberlin, Ohio, a French inventor named Paul Louis Touissant Héroult was making a related discovery in Paris. Trendy aluminum smelters now use what’s referred to as the Corridor-Héroult course of — an efficient but in addition energy-intensive and carbon-intensive manner of creating main aluminum metallic.

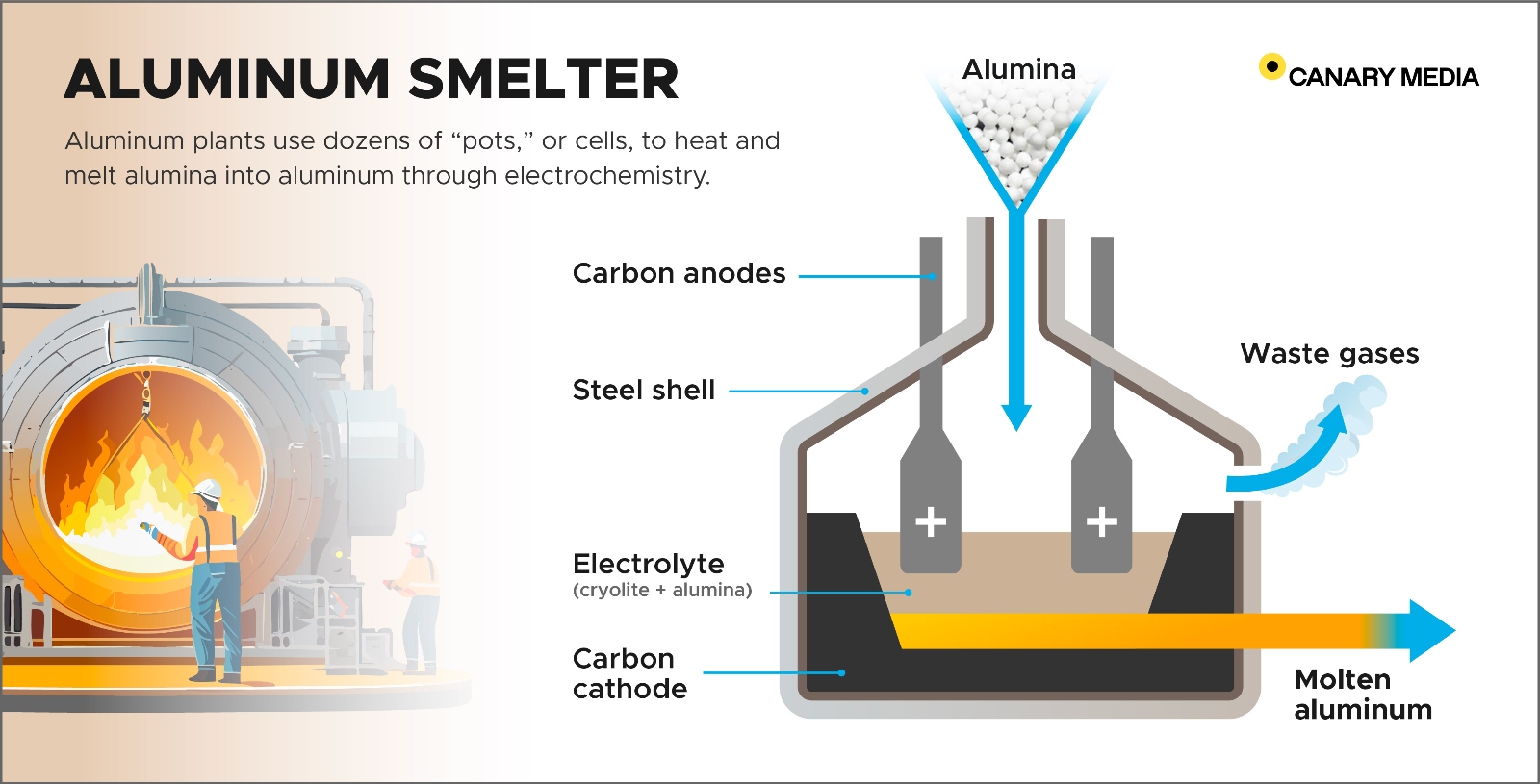

Smelting includes dissolving alumina in a molten salt referred to as cryolite, which is heated to over 1,700 levels Fahrenheit. Giant carbon blocks, or “anodes,” are lowered down into the extremely corrosive tub, and electrical currents run by your entire construction. Aluminum then deposits on the backside as oxygen combines with carbon within the blocks, creating carbon dioxide as a byproduct.

At the moment, this electrochemical course of contributes about 17 % of the entire CO2 emissions from international aluminum manufacturing. It additionally causes the discharge of perfluorochemicals (PFCs) — potent and long-lasting greenhouse gases — in addition to sulfur dioxide air pollution, which might hurt folks’s respiratory techniques and injury bushes and crops. In 2021, PFCs accounted for greater than half the emissions from Century’s Hawesville smelter and a third of the emissions from its Sebree smelter in Robards, Kentucky, in line with the Sierra Membership.

Newer smelters can dramatically scale back their PFC emissions through the use of automated management techniques, which Century deploys at its smelter in Grundartangi, Iceland. Researchers are additionally working to slash CO2 by growing carbon-free blocks. The know-how includes utilizing chemically inactive, or “inert,” metallic alloys within the anodes by which {the electrical} currents move. Elysis, a three way partnership of Alcoa and the mining large Rio Tinto, says it’s making progress towards the large-scale implementation of its inert anodes and has plans for a demonstration plant in Quebec.

The choice anodes will not be prepared in time for a mission like Century’s deliberate inexperienced U.S. smelter. Beforehand, large-scale patrons of aluminum, reminiscent of automakers and development corporations, had anticipated that inert anodes would assist slash CO2 emissions within the aluminum provide chain in time for corporations to satisfy their 2030 local weather objectives. However now that’s trying much less probably.

“There’s a feeling now that it’s simply taking longer to develop that know-how,” mentioned Lachlan Wright, a supervisor of the local weather intelligence program at RMI, a clear vitality suppose tank. One problem would possibly merely be the restricted manufacturing capability for the brand new anodes, which might’t but meet the calls for of a giant aluminum person. Past that, “It’s not precisely clear what a few of the limitations are there,” Wright added.

Nonetheless, on the subject of tackling aluminum’s greatest CO2 offender — all of the electrical energy it takes to run a smelter — the options exist already, within the type of renewable vitality and different carbon-free sources.

“We don’t want a new or rising know-how,” Sartor mentioned. “We’d like large quantities of present know-how, and it must be accessible in locations that work for the {industry}.”

Deep within the coronary heart of Kentucky’s coal nation, the scarred and treeless lands of former floor mines are more and more being repurposed to produce that clear vitality.

On one other sun-blasted day in early August, I met with Mike Smith in Hazard, a metropolis of some 5,300 people who’s enveloped by the Appalachian Mountains and constructed alongside the winding curves of the North Fork Kentucky River.

We hopped in his white pickup truck and headed towards his household’s 800-acre property. For years, they leased the land to Pine Department Mining, which dynamited the mountaintop to succeed in coal seams buried beneath the floor. “I can’t say that I was for it,” Smith informed me as we drove previous modest houses tucked into creekside hollers and up a bumpy gravel street. At the moment, he mentioned, “the one coal that’s left right here is below the river.”

After the mine closed a decade in the past, the land was reclaimed: smoothed out, packed down, and coated with vegetation to stop erosion. Now, the property is about to bear its newest transformation, as the house of the 80-megawatt Vivid Mountain Photo voltaic facility.

Maria Gallucci/Canary Media

Avangrid, the lead developer, plans to start putting in photo voltaic panels right here subsequent 12 months, in line with Edelen Renewables, the mission’s native growth accomplice. Edelen can also be serving to to advance different “coal-to-solar” initiatives within the area, together with the 200 MW Martin County Photo voltaic Undertaking below development in addition to BrightNight’s 800 MW Starfire set up. Rivian, the electric-truck maker, has signed on because the anchor buyer for the $1 billion Starfire mission, which is within the early levels of growth.

Constructing on outdated mining websites may be dearer and logistically trickier than, say, placing panels on flat, stable farmland. For one, hauling tools to the previous mines requires driving large, heavy automobiles up slender mountain roads. Smith’s website is split into uneven tiers of unpaved land. On our go to, he expertly accelerated his truck up a steep dust path. After we reached the highest, I audibly exhaled with aid. Smith gently laughed.

Regardless of the challenges, there’s an apparent poetry to constructing clear vitality in a place that when yielded fossil fuels. Ideally, it may possibly additionally convey justice to communities which are nonetheless hurting economically and spiritually from the coal {industry}’s inexorable decline. Vivid Mountain and different coal-to-solar developments are projected to generate tens of millions of {dollars} in native tax income over their lifetimes, utilizing land that was left unsuitable for something apart from cattle grazing.

“You’ve received to reinvent your self,” Smith informed me as we gazed on the empty expanse of land the place the photo voltaic mission will ultimately stand. Dragonflies darted by, and a quail referred to as from someplace on the property. “That’s the one manner we will survive.”

The following day, I met Adam Edelen, the founder and CEO of Edelen Renewables, at his workplace in downtown Lexington. Sitting in a wicker rocking chair and sipping a pint glass of candy tea, Edelen lamented the years of “outright hostility” to renewable vitality growth within the state. Nonetheless, some Kentucky policymakers are beginning to acknowledge the necessity to clear up the state’s electrical energy sector — if not explicitly to sort out local weather change, then a minimum of to draw producers like Century Aluminum that wish to energy their operations with carbon-free vitality sources.

Edelen Renewables

“Now, we’re on this headlong rush to verify we’ve received a diversified vitality portfolio to satisfy the wants of the non-public sector,” Edelen mentioned. For Century specifically, he added, “The problem is that they want low cost energy they usually want inexperienced vitality, neither of which Kentucky has a lot of.”

Electrical energy accounts for about 40 % of a smelter’s complete working bills. To stay value aggressive, aluminum producers have to hit a “magic benchmark” of round $40 per megawatt-hour, mentioned Wright of RMI. Presently, power-purchase agreements for U.S. renewable vitality initiatives are within the vary of $50 to $60 per megawatt-hour — a important distinction for amenities that may devour 1 megawatt-hour of electrical energy simply to provide a single metric ton of aluminum.

Provisions within the Inflation Discount Act might assist to slender that worth hole for Century and different main aluminum makers.

The 45X manufacturing tax credit score is a keystone of the IRA, which President Joe Biden signed into legislation two years in the past. The inducement permits producers of crucial supplies, photo voltaic panels, batteries, and different varieties of “superior manufacturing” merchandise to obtain a federal tax credit score for as much as 10 % of their manufacturing prices, together with electrical energy.

The IRA additionally put aside one other $10 billion for the 48C funding tax credit score, an Obama-era program that’s now accessible to assist producers set up tools that reduces emissions by 20 %. Aluminum producers might use the tax credit score to cowl the price of know-how that improves their working effectivity whereas additionally slashing CO2 air pollution.

Edelen Renewables says the 48C tax credit score will apply to all of the coal-to-solar initiatives, which the corporate hopes can provide a few of the electrical energy wanted for Century’s inexperienced smelter. Underneath the expanded program, renewable vitality initiatives in-built “vitality communities,” together with former coal mine websites, can obtain tax credit value as much as 40 % of mission prices, considerably decreasing the ultimate value of electrical energy related to the installations.

Japanese Kentucky “has performed such a important function in powering the nation’s economic system for the final 100 years,” Edelen mentioned. Coal communities “deserve a place within the newer economic system, they usually’re hungry for that.”

Edelen Renewables

Over in Ashland, John Holbrook mentioned he’s anxiously watching to see if northeastern Kentucky will discover its place within the nation’s inexperienced industrial transition. If Century selects the area to host its new aluminum smelter, the realm’s commerce councils and union apprenticeship packages shall be greater than prepared to start out coaching and recruiting staff, he mentioned.

However Holbrook and different native labor leaders aren’t holding their breath. A number of folks I spoke to recalled the elation they felt in 2018 when the corporate Braidy Industries broke floor close to Ashland on a $1.5 billion aluminum rolling mill — and the heartbreak that adopted years later when Braidy backtracked on the plant and its promise of a whole bunch of jobs. Braidy’s former CEO was later accused of deceptive the corporate’s board members, state officers, and journalists concerning the mission’s true monetary standing.

Whereas the Braidy scandal was a distinctive affair, the fallout nonetheless lingers in discussions about Century’s inexperienced smelter. “I feel they’d have to start out shifting trailers in earlier than we’d really feel assured to start out saying, ‘Yeah, that is actually occurring,’” Holbrook mentioned from behind his broad picket desk.

Nonetheless, he stays “cautiously optimistic” concerning the prospect of Century constructing its aluminum plant right here. “It will be region-changing,” he mentioned. “And life-changing.”