For decades, he was a symbol of justice.

A real-life lawman whose story inspired films, TV series, and generations of police officers.

Today, that legend is unraveling.

In a small town in Tennessee, people are being forced to confront a painful question:

What if their hero was never innocent?

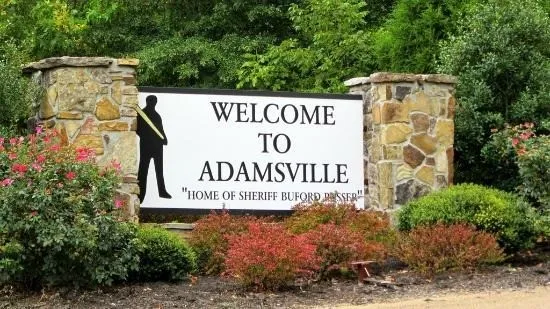

A Town Defined by One Man

On October 27, residents of Adamsville gathered for a tense town hall meeting.

The issue at hand was not a budget vote or zoning dispute.

It was the future of the town itself.

Adamsville is often called “the largest small town in Tennessee.”

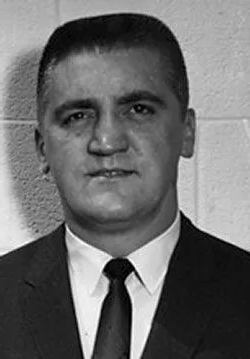

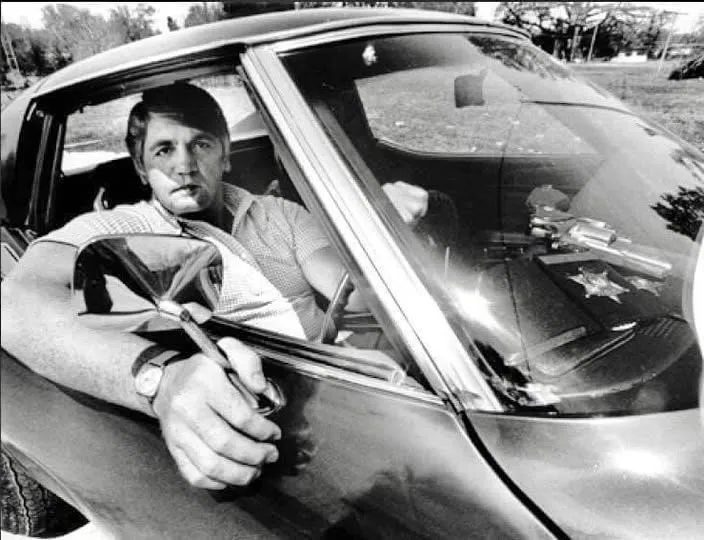

But it is far better known as the hometown of the late legendary sheriff Buford Pusser.

Many outside the United States have never heard his name.

But among older Americans, especially those who came of age in the 1960s and 1970s, Pusser represents a very specific kind of American dream.

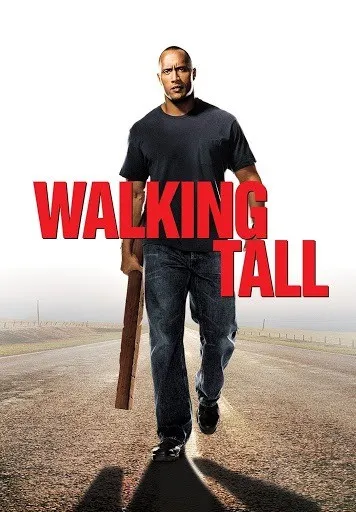

From Real Sheriff to Screen Icon

Buford Pusser became famous for cracking down on bootlegging, prostitution, gambling, and organized crime along the Tennessee–Mississippi border.

While he was still alive, his story was already turned into popular culture.

In 1973, the film Walking Tall premiered, based directly on his life.

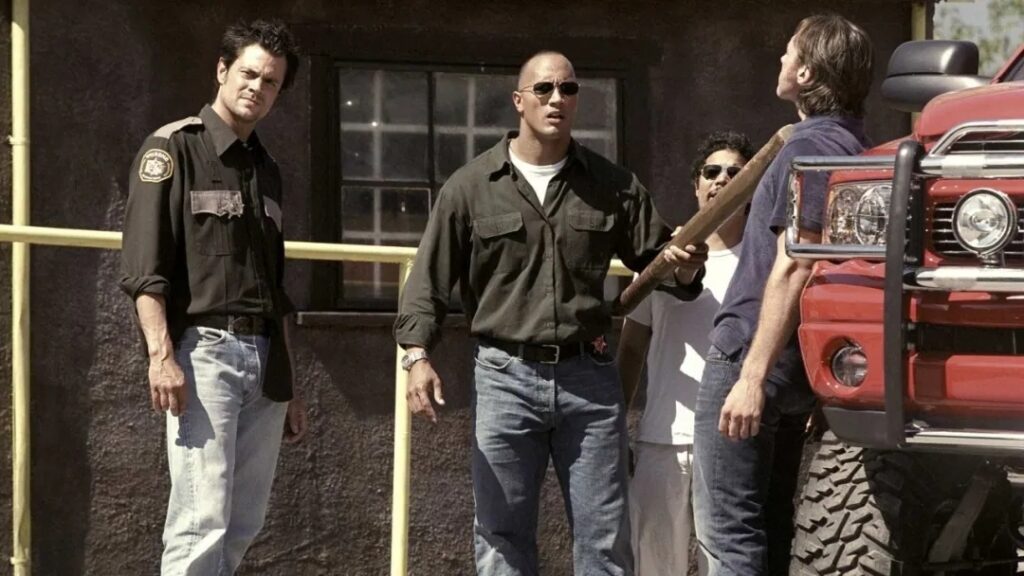

It was followed by two sequels, a television series, and a 2004 remake starring Dwayne Johnson.

On screen, Pusser was portrayed as a fearless Southern sheriff.

He fought criminals with brute force and carried an oversized wooden club.

The image was unforgettable.

That portrayal turned him into a law enforcement icon.

In the United States, there is even an award named after him, the Buford Pusser Award.

It is given to police officers each year during the annual Buford Pusser Sheriff’s Festival in Adamsville.

For the town, Pusser is everything.

A Town Built on a Legend

With a population of just over 2,000, Adamsville has invested heavily in preserving his image.

There is a Buford Pusser Museum, a memorial center, a water tower bearing his face, and a highway named after him.

The original Walking Tall film earned around $60 million at the box office in 1973.

Millions of Americans learned his name through that movie.

One scene moved audiences deeply.

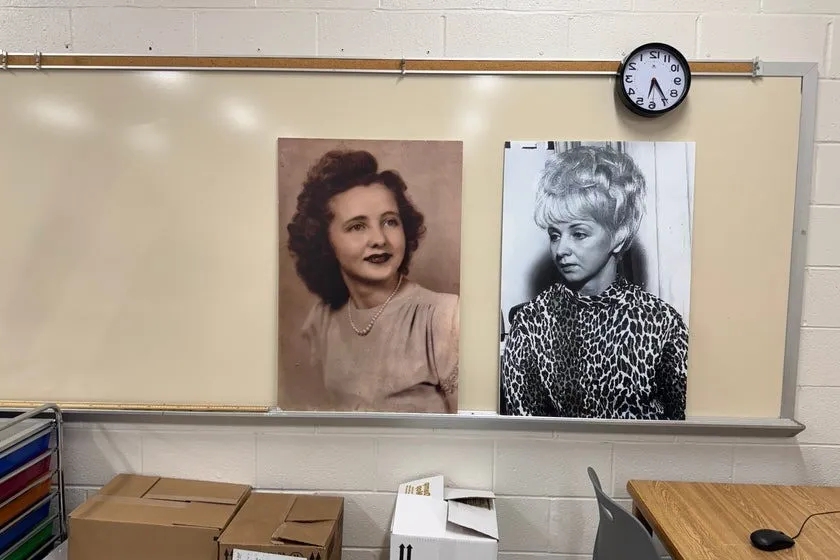

In the film, Pusser’s wife, Pauline, is murdered by local mobsters.

That part of the story, it turns out, was real.

The Death of Pauline Pusser

Pauline Pusser was killed several years before the movie’s release.

At the time, authorities concluded that organized crime was responsible.

For more than fifty years, that explanation went largely unquestioned.

Then, in August 2024, the Tennessee Bureau of Investigation released new findings.

According to investigators, Pauline’s killer may not have been a gangster at all.

They believe the truth had been hiding in plain sight.

Buford Pusser Before the Myth

In 1964, at just 27 years old, Pusser was elected sheriff of McNairy County.

He narrowly defeated the former sheriff, James Dickey, who had died in a car accident just days before the election.

Before that, Pusser’s life was unremarkable.

He briefly served in the United States Marine Corps before being discharged for asthma.

He worked at a funeral home, tried boxing under the nickname “Bull Buford,” and drifted between jobs.

In 1959, he married Pauline, a divorced woman with two children.

Violence, Power, and Control

After a violent confrontation at a bar called the Plantation Club, Pusser returned to Adamsville.

He eventually took over as sheriff, replacing his own father.

During his two terms, he waged an aggressive campaign against local criminal networks.

In one incident, he shot and killed Louise Hathcock, alleged to be a financial backer of organized crime.

She was shot in the back, but Pusser claimed self-defense.

Despite controversies, his reputation grew.

Until August 1967.

The Night Pauline Died

At 4 a.m., Pusser left home to respond to a reported disturbance near a church.

For reasons still unclear, Pauline went with him.

Hours later, she was dead in the car.

Pusser said mobsters had lured him into an ambush using a fake police call.

He claimed a vehicle opened fire, killing Pauline.

He said he was then shot in the jaw while chasing the attackers.

The story became legend.

Fame and National Adoration

Two years later, CBS filmed a feature on Pusser’s tragic story.

Book deals, film contracts, and speaking tours followed.

Newspapers called him a “Southern folk hero.”

Movies based on his life earned over $100 million worldwide.

In an era defined by racial segregation, Pusser hired the county’s first Black deputy sheriff.

That decision further elevated him as a civil rights symbol.

A Case Reopened

In 2023, the Tennessee Bureau of Investigation reopened Pauline’s murder case.

Most witnesses were dead.

Evidence had been lost to fires, floods, and neglect.

Still, investigators used modern techniques, including blood spatter analysis, firearm tracing, and drone reconstructions.

Their findings contradicted Pusser’s account.

What the Evidence Suggests

In 2024, Pauline’s body was exhumed.

Investigators discovered she had been shot twice in the back of the head.

Her nose was also broken by blunt force trauma.

Investigators believe the weapon was a handgun from Pusser’s personal collection.

The caliber matched the bullets that killed Pauline.

They now suspect Pusser shot his wife at home, dressed her body, placed her in the car, and staged the ambush.

He may have shot himself in the jaw afterward to complete the illusion.

Motive and Silence

Why would he do it?

Investigators believe Pauline was preparing to leave him.

Friends said she had packed bags and secretly moved clothes out of the house.

After her death, their home burned down.

Nothing remained but the foundation.

A Community Divided

Even today, Adamsville is split.

Some residents insist Pusser was corrupt, violent, and dangerous.

Others refuse to accept the findings.

At the October town meeting, prayers were offered in Pusser’s name.

Pauline was never mentioned.

His granddaughter, a former Miss USA, told residents she believed her grandfather was innocent.

She dismissed the investigation as speculation.

The Power of Myth

For many in Adamsville, the truth is less important than the story.

The museum may close if the legend collapses.

Tourism could disappear.

So could the town’s identity.

One resident summed it up simply:

“A myth lasts longer than a man. Longer than the truth.”

And in Adamsville, that myth still walks tall.