September 17, 2024

3 min learn

Ebook Evaluate: How One Bizarre Rodent Ecologist Tried to Change the Destiny of Humanity

A biography of the scientist whose work led to fears of a ‘inhabitants bomb’

NONFICTION

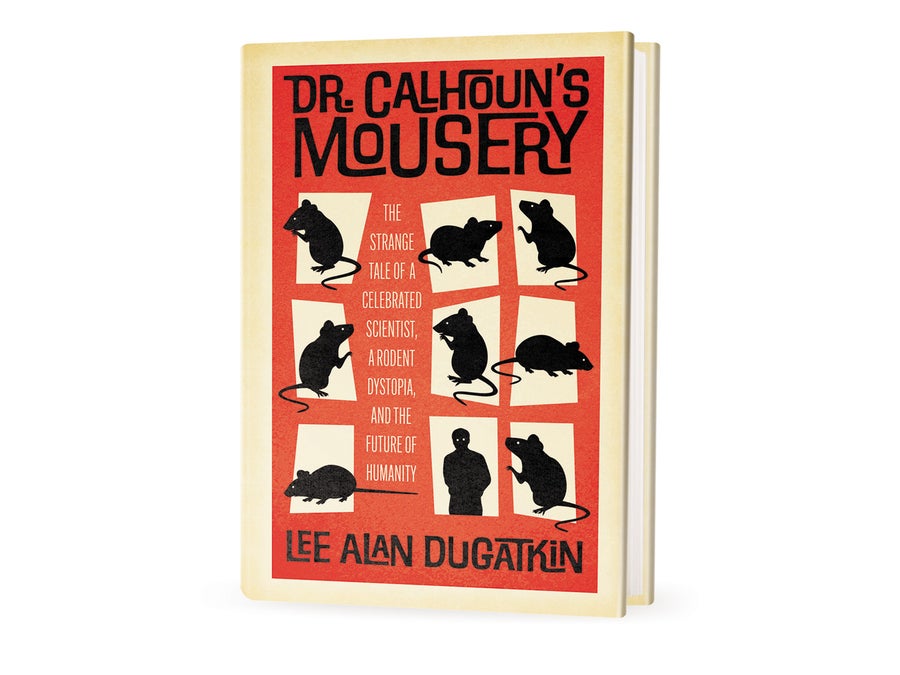

Dr. Calhoun’s Mousery: The Unusual Story of a Celebrated Scientist, a Rodent Dystopia, and the Way forward for Humanity

by Lee Alan Dugatkin

College of Chicago Press, 2024 ($27.50)

Within the Sixties and Seventies American society suffered a yearslong collective panic concerning the perceived menace of overpopulation. Biologist Paul Ehrlich appeared on The Tonight Present to tout The Inhabitants Bomb, his 1968 polemic about human numbers run amok. The 1973 movie Soylent Inexperienced depicted a squalid hellscape by which surplus individuals can be processed into meals. Faculty college students pledged to stay childless for the good thing about Earth.

On supporting science journalism

Should you’re having fun with this text, think about supporting our award-winning journalism by subscribing. By buying a subscription you’re serving to to make sure the way forward for impactful tales concerning the discoveries and concepts shaping our world immediately.

This anxiousness originated, partially, within the laboratory of John Bumpass Calhoun, an enigmatic ecologist who spent many years documenting the opposed results of overcrowding on rodents in elaborate experimental “cities.” Calhoun is essentially obscure immediately, however few scientists in his time wielded extra affect. He hobnobbed with science-fiction author Arthur C. Clarke and was featured in books by naturalist E. O. Wilson and journalist Tom Wolfe—within the course of spreading overpopulation angst far and huge. “Essentially the most profound impression of Calhoun’s research lies removed from educational halls and ivory towers,” writes Lee Alan Dugatkin in Dr. Calhoun’s Mousery, a brand new biography almost as quirky as its topic. Calhoun’s work completely “seeped into the general public consciousness.”

Calhoun made for an unlikely prophet. A nature lover from Tennessee, he took a job within the Forties main a long-term examine in Baltimore with the first aim of controlling city rats. Calhoun discovered that every metropolis block was house to round 150 rats, a quantity he discovered low given the “considerable sources of meals in open rubbish cans.” Rat populations, he suspected, had been “self-regulating”: when new rats tried to maneuver in, residents kicked them out. However the unpredictability of Baltimore’s streets— the place people had been continuously killing rats or messing with the traps—pissed off Calhoun’s analyses. To really perceive rat society, he determined, he wanted to manage their surroundings.

Within the late Fifties the Nationwide Institute of Psychological Well being gave Calhoun the chance to control rats in a reworked Maryland barn. Calhoun, an endlessly creative designer of experiments, constructed an enclosure outfitted with rat flats and partitioned the pen into related “neighborhoods,” making a murid arcadia that he might observe at his leisure.

This utopia quickly turned nightmarish. Because the rats multiplied, they fed and gathered in ever better densities, resulting in a social breakdown that Calhoun referred to as a “behavioral sink.” Packs of libidinous males relentlessly hounded females, who in flip ignored their offspring; in some neighborhoods, pup mortality hit 96 %. The rats, Calhoun declared, suffered from “pathological togetherness” that might result in collapse. Within the years that adopted, he shifted to mice, however his basic conclusions remained the identical: rodents succumbed to chaos as their populations exploded.

Calhoun wasn’t shy about extrapolating to our personal species’ destiny. “Maybe if inhabitants progress continues to develop unchecked in people, we’d in the future see the human equal” of socially catatonic rodents, he informed the Washington Day by day Information in a single attribute interview. His fears each channeled the zeitgeist and directed it.

Dugatkin—an evolutionary biologist, science historian and prolific creator who sifted by means of 1000’s of pages on the Calhoun archive in Bethesda—is an admirably thorough researcher. However his granular chronology of Calhoun’s actions generally slides too deep right into a recitation of media protection, convention talks and complex experiments. Amid this blizzard of trivialities, Mousery sometimes loses sight of a query that ought to be central to any biography: Why does Calhoun matter immediately? Dugatkin acknowledges that the “lasting impression of [Calhoun’s] work is nowhere close to” that of pioneering behaviorists comparable to Ivan Pavlov. However he misses a possibility to probe the social debates that his topic’s work catalyzed. Did Calhoun’s darker prognostications do hurt? The inhabitants bomb, in any case, didn’t detonate.

Calhoun belonged to a technology of scientists who had no compunctions about straying from their disciplinary lane. He wrote poetry and sci-fi and consulted on humane jail design. Dugatkin captures the grand ambition of a person who gazed at rodents and noticed the universe, even when the importance of his analysis is murky immediately. As Dugatkin notes, the disturbing dynamics that Calhoun produced in his micromanaged “universes” have by no means been noticed within the wild. Calhoun didn’t describe the world; he created his personal.