On certainly one of his few lucid moments throughout the one debate of the 2024 election cycle between Donald Trump and Joe Biden, the sitting president steered he could be harder on the border than his predecessor, blaming the previous president for the demise of a “bipartisan border deal” that may have boosted the Border Patrol’s funding and considerably lowered entry to asylum. Biden and high congressional Democrats had spent months negotiating its provisions, granting increasingly more concessions to conservatives within the hopes that they’d cease claiming that Biden had misplaced management of the southern border. However “after we had that deal performed,” Biden mentioned, Trump “known as his Republican colleagues and mentioned, ‘Don’t do it. It’s going to harm me politically.’” The far proper had refused to grant Biden a “win” on immigration, even when it meant forgoing precisely what they claimed they wished.

This was a really totally different Biden than the one who had gone up towards Trump 4 years earlier. When the 2 shared a debate stage in 2020, Biden accused Trump of presiding over unimaginable cruelty towards migrants: infants torn from their moms’ arms on the border, some by no means to be reunited; undocumented employees rounded up on the job; asylum seekers shunted again to Mexico and not using a listening to. However there Biden was, just a little over three months in the past, saying in impact that he’d tried to complete the job Trump had begun, solely to be stymied by Trump himself.

Biden’s pronouncements would quickly take a backseat to the flurry of concern over his pitiful debate efficiency and his visibly declining well being. He quickly dropped out of the race, passing the torch to Vice President Kamala Harris, whom he’d as soon as tasked with addressing the “root causes” of migration from Central America. However Biden’s pivot within the debate and the months previous it symbolized a rightward lurch on immigration that will have been initiated by the GOP however has since change into the dominant place of the Democratic Social gathering. In the meantime, in his marketing campaign to get again to the White Home, Trump has tacked even additional to the correct. Immigrants, Trump has mentioned, are “poisoning the blood of our nation.” If elected, he’s declared to thunderous applause, he’ll start “mass deportations” on day one. “Ship them again!” the gang chanted when “unlawful aliens” had been talked about on the Republican Nationwide Conference in Milwaukee, holding indicators that learn “Mass Deportation Now!”

This shift got here stunningly quick. Simply three election cycles in the past, within the aftermath of Mitt Romney’s loss within the 2012 election, a postmortem by the Republican Nationwide Committee (RNC) attributed Romney’s defeat to his poor efficiency amongst Latino voters and advisable that the occasion ought to change into extra inclusive, maybe softer on immigration. Even Trump—on the time an outspoken businessman with no public political ambitions—mentioned that Romney’s stance on immigration was ridiculous. “He had a loopy coverage of self-deportation, which was maniacal,” Trump mentioned in 2012. “It sounded as dangerous because it was, and he misplaced the entire Latino vote. He misplaced the Asian vote. He misplaced all people who’s impressed to return into this nation.” Three years later, saying his personal run for president, Trump descended a gilded escalator at Trump Tower on Fifth Avenue and promised to construct an impenetrable border wall. All through his 2016 marketing campaign, Trump ignored the RNC’s suggestions and embraced the ethos of the Tea Social gathering, channeling incoherent populist rage right into a nativist platform.

The guarantees of mass deportations and a “large, lovely wall” had been all Trump, however a coverage wonk he was not. Trump’s immigration coverage was devised by the alumni and allies of a single ecosystem of intertwined assume tanks, nonprofits, and advocacy teams—one that after operated largely on the margins however that, starting with Trump’s ascension to the presidency, has set the tone of the nationwide immigration debate. Few of Trump’s immigration insurance policies survived authorized problem, and even fewer are nonetheless in place right now. Congress didn’t go a single immigration invoice throughout Trump’s time period, nor has it beneath Biden. However immigration restriction is now dogma amongst Republicans and Democrats alike. The selection is now not between a celebration that desires to show away migrants and one which claims to welcome them, however slightly between opposing sides that, regardless of their broader variations, disagree solely on one of the best ways to “safe” the border at any value.

It’s not an overstatement to say that the trendy immigration restriction motion owes its existence to at least one man: a charismatic eye physician from rural Michigan named John Tanton. As soon as described by a former ally as “probably the most influential unknown man in America,” Tanton spent a long time constructing a community of anti-immigration teams from the bottom up, reworking submit–World Conflict II nativism from a fringe view held by a small group of white supremacists right into a mainstream political motion. Tanton, a veteran of the mid-century conservationist and inhabitants management actions, noticed inhabitants progress as a significant hurdle to long-term sustainability. Making an attempt to persuade his fellow nature lovers of the connection between worldwide migration and environmental spoil, Tanton based the Federation for American Immigration Reform, or FAIR, in 1979, dedicating himself to reversing the demographic adjustments that had taken maintain in America in his lifetime. Over the subsequent three a long time, Tanton would discovered and assist present funding for a constellation of anti-immigration advocacy teams, together with the Heart for Immigration Research (CIS), U.S. English, and NumbersUSA.

Tanton was born in Detroit in 1934, a decade after the Immigration Act of 1924 put the primary everlasting numerical limits on immigration in US historical past. The laws capped immigration from Europe and allotted slots utilizing a quota based mostly on the composition of Individuals’ nationwide origins as of the 1890 census. The impact was a right away and drastic discount in immigration from Southern and Japanese Europe: Greater than one million European immigrants arrived in america in 1907; in 1925, that determine was simply over 160,000. Because of the act, Southern and Japanese Europe had been now not the principle supply of immigrants to the US. (African and Asian migration had been successfully banned; no restrictions had been carried out on migration from Latin America.)

The 1924 legislation stored America overwhelmingly white and Western European by Tanton’s younger maturity. However in 1965, a yr after he graduated medical faculty, the nation modified without end. The Immigration Act of 1965, also called the Hart-Celler Act, overturned the national-origins quota system, changing it with one which prioritized household reunification. The brand new legislation greater than doubled the variety of immigrant visas issued annually and didn’t depend the speedy kin of US residents towards these quotas. On the similar time, Hart-Celler imposed numerical limits on Latin American and Caribbean migration for the primary time in US historical past, unwittingly creating the situations for an increase in unauthorized migration a long time later. The legislation led to new patterns of immigration that slowly shifted America’s racial composition. The descendants of the Southern and Japanese European immigrants who had been thought of unassimilable a long time earlier had been, after a rocky begin, included into the American melting pot; the newcomers, in the meantime, had been regarded with hostility, accused of being inferior to the era of immigrants who had come earlier than them.

As was the case on the flip of the twentieth century, the wave of immigrants who arrived after 1965 had been met with hostility. In 1977, David Duke, the grand wizard of the Ku Klux Klan, mentioned that he and his followers could be patrolling the US-Mexico border in the hunt for migrants. Two years later, Klan members descended on a Texas fishing village that had not too long ago change into residence to Vietnamese refugees.

Tanton and his spouse had been largely insulated from these adjustments in Petoskey, the tiny northern Michigan city the place he discovered work as an ophthalmologist. A decade earlier, on the finish of the Sixties, Tanton had learn The Inhabitants Bomb, the biologist Paul Ehrlich’s polemic on overpopulation. For Tanton, every refugee who resettled in America meant one other drain on assets, one other blight on the surroundings. He conceived of FAIR as a liberal anti-immigration group, and its early speaking factors had been about how unfettered immigration damage working-class folks of coloration at residence and contributed to a mind drain overseas, to not point out its results on inhabitants progress.

All these a long time later, it’s onerous to understand how out of step this was. After Hart-Celler and earlier than FAIR’s emergence as a significant political participant, immigration restriction was the area of Klansmen and white separatists. It wasn’t, as Tanton wrote in his 1978 funding request to Cordelia Scaife Might—the reclusive Mellon heiress who would go on to bankroll his motion—“a authentic place for considering folks.”

The primary take a look at arrived shortly. Months after FAIR’s founding, Congress started engaged on the Refugee Act of 1980, an effort to streamline the advert hoc system that allowed folks fleeing their nations to seek out safety in america. FAIR employed a lobbyist to push for a provision that may cap the variety of refugees admitted annually at 50,000. As a substitute, the invoice that President Jimmy Carter signed into legislation allowed the sitting president to decide on the annual restrict in session with Congress. That yr, greater than 207,000 refugees had been resettled in america. Six years later, FAIR as soon as once more acquired caught up in—and misplaced—a legislative battle, this time over the 1986 Immigration Reform and Management Act, which offered a path to citizenship for almost 3 million undocumented immigrants dwelling within the US. The invoice handed with bipartisan consensus, and President Ronald Reagan signed it into legislation. Few in Congress had been swayed by FAIR’s arguments for deporting unauthorized immigrants. “We didn’t persuade anyone,” founding member Otis Graham instructed The New York Occasions in 2011. FAIR had constructed a membership base of 4,000 by 1982, however it wasn’t sufficient for Tanton, who, based on notes taken throughout a board assembly that yr, believed it was “time to alter our strategies.” Tanton was realizing that environmental points didn’t attraction to most Individuals; what did was watching their communities change and feeling powerless to cease it. In a 1986 memo, Tanton wrote that FAIR had been too reliant on massive donors and too targeted on lobbying members of Congress, with little to point out for it. As a substitute, he outlined a “long-range challenge” to “infiltrate” congressional immigration committees. “Suppose how a lot totally different our prospects could be if somebody espousing our concepts had the chairmanship!” he wrote. Till then, it might be troublesome to affect nationwide politics. Tanton determined to begin small.

Tanton acquired his first likelihood to check his new idea of the facility of a grassroots immigration restriction motion in 1988, when one other group he’d based earlier that decade, U.S. English, positioned the query of language on the poll. Tanton had created U.S. English to assist arrange campaigns to make English the official language of a number of states, a few of which had massive and steadily rising Latino populations. The campaign started in California, the place U.S. English bankrolled a neighborhood group’s efforts in assist of an English-only poll initiative. After the California measure succeeded, U.S. English led related campaigns in a far-flung mixture of states, together with Arkansas, Mississippi, North Carolina, North Dakota, and South Dakota in 1987, and Arizona, Colorado, and Florida the next yr. Some had been states the place the demographics had been shifting, whereas others, like North Dakota, had been attempting to preempt these adjustments. In all, nonetheless, the query was about greater than language; it was about who belonged in America—and to whom it ought to belong sooner or later.

The English-only campaigns had been marred by allegations of racism from the outset. Opponents criticized Tanton’s teams for taking cash from the Pioneer Fund, a New York–based mostly eugenicist group. But it surely wasn’t till somebody leaked a memo from Tanton written two years earlier that the Arizona marketing campaign appeared doomed. “Can homo contraceptivus compete with homo progenitiva if borders aren’t managed?” he mused within the 1986 memo, which was distributed to attendees of the annual anti-immigration retreat he had begun internet hosting a yr earlier. “Or is recommendation to restrict one’s household merely recommendation to maneuver over and let another person with larger reproductive powers occupy the area?” He posed different troubling questions within the memo: Will Latino Catholics be capable of assimilate to American tradition? Will they carry their customs of bribery, violence, and disrespect for authority to america? And why have they got so many children within the first place?

The individuals who attended Tanton’s retreat—together with Jared Taylor, the writer of the white nationalist journal American Renaissance—should have welcomed these questions, however the public didn’t. Regardless of U.S. English’s bipartisan background and high-profile endorsements—its first director was former Reagan aide and distinguished Latina activist Linda Chavez, and Walter Cronkite was on the board—it may now not declare believable deniability relating to allegations of racism. Chavez resigned after the memo leaked and disavowed the group; Cronkite, too, bailed. However with the assistance of a last-minute canvassing push funded by Might, U.S. English eked out a victory, with 50.5 p.c of Arizona voters supporting the measure. The elections weren’t as shut elsewhere within the nation: Greater than 60 p.c of Colorado’s voters supported the modification, as did 84 p.c of Florida’s.

There was a setback: A federal choose later blocked Arizona’s English-only measure. Even so, grassroots activism, Tanton got here to know, was the important thing to enacting insurance policies that curtail immigration. All Tanton needed to do was assist folks understand what they already knew of their hearts to be true: America was a nation of immigrants, sure, however the newcomers had been in contrast to those that got here earlier than. “I believe there may be such a factor as an American tradition, nonetheless troublesome it could be to outline,” Tanton mentioned in a 1989 oral historical past of his advocacy. Some may argue that “hyphenated Individuals” belong to this tradition simply as a lot as folks whose forebears date again to the colonial interval, Tanton mentioned, however that was “an incorrect view.” In a 1986 interview with The New York Occasions, FAIR’s first govt director, Roger Conner, a former environmental lawyer, described earlier waves of immigrants as “entrepreneurial,” whereas newer arrivals had little curiosity in working or assimilating. “For some motive,” Conner mentioned, “Mexican immigrants usually are not succeeding in addition to different teams.”

By 1990, FAIR claimed to have 50,000 members, and the group was discovering different state-level initiatives to assist. In 1994, the group backed Proposition 187, a poll initiative in California that banned undocumented immigrants from utilizing any authorities companies within the state, together with public colleges and non-emergency healthcare. In 1986, Tanton had written that California’s system may do that, “however the political will is missing to implement it.” To construct that may, Tanton created and funded teams like Individuals for Border Management by his umbrella group, U.S. Inc. Proposition 187’s supporters claimed that not solely had been the undocumented overburdening public companies and contributing to overcrowding within the state, however their presence in California would result in long-term features in political energy for Hispanic Individuals.

Practically 60 p.c of Californians voted for Proposition 187, however a federal choose blocked the initiative from going into impact. Nonetheless, as with Arizona’s English-only measure, the defeat of Proposition 187 offered a precious lesson for FAIR: Change occurs when peculiar folks resolve they’re fed up with one thing and are available collectively to do one thing about it. If the teams that enable folks to do this don’t exist, why not create them?

In every single place they handed, anti-immigrant ordinances like Proposition 187 and the English-only measures granted a level of legitimacy to long-held racial animus. In Colorado, somebody posted an indication studying “No Ingles, No Travato“—an tried translation of “No English, No Job”—on the entrance to a development web site. “We checked. Due to the English-only invoice, we all know it’s authorized,” a superintendent on the web site instructed the Los Angeles Occasions. In California, Proposition 187 proved to be simply as efficient a recruitment software as it might have been had it been carried out. Tanton’s journal, The Social Contract, has printed dozens of articles about Proposition 187 within the a long time because the referendum handed. “When hundreds of [people] marched to protest” the measure, an article from The Social Contract’s 1996 challenge on so-called “anchor infants” declared, “they carried the flag of Mexico, not the Stars and Stripes.”

Tanton’s organizations not solely activated dormant anti-immigrant feeling; they actively fomented it, usually utilizing the information media to launder their speaking factors. FAIR, the Heart for Immigration Research, and NumbersUSA—the latter based in 1996 by Tanton’s acolyte Roy Beck—turned reporters’ go-to sources for all issues associated to immigration restriction, largely as a result of there have been few different teams to cite. Representatives of the three organizations blamed almost each downside, from littering in public parks to gridlock on the highways, on immigration. On the peak of the tough-on-crime ’90s, immigration was being portrayed as a gangs and quality-of-life challenge; after the September 11 assaults, the permeability of the border turned a nationwide safety menace.

FAIR and its allies had been succeeding in altering public sentiment on immigration. Quickly FAIR, by its authorized arm, the Immigration Legislation Reform Institute, started providing its authorized companies to native governments. In 2006, when the town of Hazleton, Pennsylvania, handed a legislation fining landlords for renting residences to undocumented immigrants and employers for utilizing them as employees, it employed Kris Kobach, who would change into one of many foremost attorneys pushing immigration restriction. Not lengthy after, the city council of Valley Park, Missouri, unanimously voted to implement an identical coverage. Kobach defended Valley Park after a landlord sued over the measure, then went on to draft laws for different cities—and defended the cities when these insurance policies had been challenged in courtroom. The measures confronted years of lawsuits, and the cities needed to pay Kobach tons of of hundreds of {dollars} in authorized charges. “It was a sham,” the mayor of Farmers Department, a Texas metropolis that employed Kobach in 2007, instructed ProPublica, which reported that Kobach earned at the least $800,000 for his authorized and advocacy work over a 13-year interval. Ineffective and costly as they had been, the ordinances helped cement Kobach’s standing because the go-to lawyer for native and state governments that wished to take a tough line on immigration. In 2010, Kobach drafted Arizona’s notorious SB 1070, colloquially known as the “Present Me Your Papers” legislation. An Arizona state senator later described it as “mannequin laws” for dissemination by the American Legislative Alternate Council, a right-wing “invoice mill.” Copycat payments had been quickly launched across the nation. By 2012, Kobach was informally advising the Romney marketing campaign on immigration.

Many of the payments that Kobach drafted or defended had been blocked by the courts, by no means carried out, or watered right down to the purpose of meaninglessness. However each metropolis that handed and even debated an anti-immigrant ordinance helped Tanton’s teams ship a message to Congress: Individuals aren’t serious about immigration reform or amnesty for the undocumented; they need these folks out. “God forbid he ever will get hit by a Mack truck or one thing,” the Immigration Legislation Reform Institute’s basic counsel mentioned in 2012 of Kobach, who by that time was working for the group on the aspect whereas serving as Kansas’s secretary of state. “It could change the course of historical past.”

Tanton’s “long-range challenge” to have an effect on nationwide politics by beginning on the native stage was working. The organizations beneath the umbrella of FAIR and U.S. Inc. had constructed a grassroots military and gained over small-town mayors. And a few of these mayors had been now coming into nationwide politics. After three failed bids for a seat in Congress, Lou Barletta, the Hazleton mayor who employed Kobach to defend the town’s anti-immigrant ordinance, was elected to the Home of Representatives in 2010. Amongst Tanton’s different supporters had been Colorado Consultant Tom Tancredo, who kicked off his first time period in 1999 by founding the Congressional Immigration Reform Caucus; Iowa Senator Chuck Grassley; and Jeff Periods, the soft-spoken Alabama senator whose diminutive presence belied his virulent racism. In 2000, FAIR and its sister organizations helped defeat the Latino and Immigrant Equity Act, which might have offered a path to citizenship for qualifying undocumented immigrants. The next yr, within the speedy aftermath of 9/11, the Congressional Immigration Reform Caucus’s membership almost doubled in a single day, from 16 to 30 members.

Standard

“swipe left under to view extra authors”Swipe →

FAIR would face its largest assessments but starting in 2006, when Congress appeared poised to go a invoice granting inexperienced playing cards to greater than 6 million undocumented immigrants. The laws failed, however in 2007 a gaggle of senators as soon as once more tried to influence their colleagues—and the nation—to assist immigration reform. The invoice sponsored by the “Gang of 12,” together with Lindsey Graham and John McCain, had bipartisan assist and was backed by President George W. Bush. Its opponents had one thing stronger: a grassroots military, tons of of hundreds robust, who threatened to withhold their votes from politicians who put “illegals” forward of Individuals.

Most Individuals, actually, had been in favor of granting citizenship to undocumented immigrants who met sure situations—however they, too, had been swayed by the marketing campaign towards the invoice. Polls discovered that many citizens who agreed with the 2007 invoice’s provisions opposed the concept of “amnesty” and the invoice particularly. The discrepancy between what folks mentioned they wished and what they really supported was the results of a coordinated effort by FAIR, CIS, and NumbersUSA. Day by day, as a part of a marketing campaign led by NumbersUSA, lawmakers acquired hundreds of calls, letters, and faxes urging them to vote towards the invoice. “The fax machines would run out of paper,” a Republican Home staffer recalled years later. Many of the messages got here from a well-known group of individuals—“frequent fliers,” the staffer known as them—however the quantity of calls swayed those that had been undecided. The callers “lit up the switchboard for weeks,” Senator Mitch McConnell, who voted towards the invoice, mentioned in 2011, when immigration reform was again on the desk. “And to each certainly one of them I say right now: Your voice was heard.”

The 2011 invoice failed as properly and was reintroduced in 2014, this time by a “Gang of Eight”—an indication of waning assist in Congress. “The longer it stays within the solar, the extra it smells, as they are saying in regards to the mackerel,” Periods mentioned of the reform invoice in 2014. Sure that it might go within the Senate, Periods—on the time nonetheless a fringe member of his occasion—set his sights on tanking the invoice within the Home. To make sure that the laws failed, he enlisted his younger aide, a 29-year-old from California named Stephen Miller.

Miller—the son of Santa Monica liberals who would introduce himself to school classmates by saying, “My identify is Stephen Miller, I’m from Los Angeles, and I like weapons”—began his profession as a press secretary for Minnesota Consultant Michelle Bachmann. After he took a job with Periods, Miller turned shut with researchers at CIS; he used the group’s knowledge to persuade different Republicans of the harms that immigrants posed. Periods had lengthy been shut with FAIR and CIS, however with Miller’s assist, he turned a frontrunner of the anti-immigration-reform motion inside Congress and was instrumental in defeating the invoice in 2014. “The entire level was to taint the invoice within the eyes of Republicans within the Home,” CIS president Mark Krikorian instructed Miller’s biographer. “Periods, with Miller’s assist, actually did achieve stopping that invoice from passing.”

Miller, too, was influenced by Tanton, typically in obscure methods. In 1983, Tanton persuaded Might, his billionaire patron, to cowl the prices of reprinting and distributing The Camp of the Saints, a French novel that depicts a dystopian future by which Europe and the US are besieged by hordes of dark-skinned migrants. The guide didn’t obtain a lot acclaim outdoors white supremacist circles when it was first printed in 1973. However Tanton acquired the rights and organized for it to be printed by the Social Contract Press. It’s unclear when Miller learn the novel, however in September 2015, he persuaded Breitbart to run a narrative about it, based on e-mails obtained by the Southern Poverty Legislation Heart. “I believe it was rising up in California, he noticed the function that mass migration performed in turning a crimson state blue,” a former Senate colleague of Miller’s instructed Politico. “He was fearful that may occur to the remainder of the nation.”

After Trump introduced his candidacy in 2015 by calling Mexican immigrants “rapists,” Miller persuaded Periods to change into the primary sitting senator to endorse him. Miller supplied his companies as a casual adviser to the marketing campaign after which, after a couple of months, demanded a job. Trump shared Miller’s instincts; in 2014, he’d cautioned Republican legislators towards supporting immigration reform by implying that the beneficiaries of amnesty would vote for Democrats. Miller wrote Trump’s speeches and helped flip his xenophobic guarantees—a border wall, a Muslim ban—into coverage proposals. And when Trump took workplace, Miller and Periods had been rewarded: Periods was named lawyer basic, and Miller turned a senior coverage adviser for Trump. With Miller’s assist, Trump stocked his companies with alumni of the anti-immigration assume tank ecosystem. Trump appointed Francis Cissna, a former worker of FAIR ally Chuck Grassley, to go US Citizenship and Immigration Companies, the company that oversees authorized migration. Julie Kirchner, the chief director of FAIR from 2007 to 2015, was employed to advise the performing director of Customs and Border Safety in April 2017, earlier than shifting to USCIS a month later. Throughout his first few months in workplace, Trump carried out dozens of insurance policies—together with increasing immigrant detention, reviving partnerships between Immigration and Customs Enforcement and native legislation enforcement companies, and expediting sure deportation proceedings—that appeared to have been lifted from a 2016 want listing that CIS had printed earlier than Trump secured the nomination. In 2017, for the primary time, CIS was invited to ICE’s semiannual stakeholder assembly. Representatives from FAIR and NumbersUSA additionally attended.

However Trump’s Division of Homeland Safety was tumultuous. Staffers resigned with an alarming frequency, usually after Miller pressured them to implement more and more hard-line insurance policies. Miller and a key ally, Gene Hamilton, senior counsel for Trump’s first DHS secretary, spent months pushing for a household separation coverage on the US-Mexico border. Elaine Duke, Trump’s second DHS secretary, balked; Kirstjen Nielsen, her successor, ultimately gave in to the strain. It didn’t fare properly for her: After mass protests and requires congressional inquiries, Trump ended the household separation coverage and Nielsen handed in her resignation.

Miller’s place as an adviser to the president gave him broad latitude within the White Home. “The method for making selections didn’t exist after we got here in,” an immigration official within the Biden administration not too long ago instructed The New Yorker. “It was calls with Stephen Miller by which he yelled on the profession officers, they usually went off to do what he mentioned, or to attempt.”

For a quick second within the wake of biden’s 2020 victory towards Trump, immigrant advocacy teams felt aid. The nation had voted towards separating migrant households and banning Muslims. This optimism was minimize brief by Republicans, who began to spout immigrants-are-invading rhetoric nearly as quickly as Biden took workplace. Two months into Biden’s time period, the Heritage Basis accused him of inflicting a “disaster” on the southern border. Miller and his crew seized the narrative early, pushing the Biden administration right into a defensive posture. Biden’s staff shortly deserted the guarantees that they had made in the course of the 2020 marketing campaign to undo the harms that had been perpetrated by Trump’s DHS and to construct a brand new, humane immigration system as an alternative. Whereas Biden has rolled again a few of Trump’s harshest insurance policies on the border and created pathways for migrants from sure nations to lawfully enter and work in america on a short lived foundation, these are half-measures at finest.

Public sentiment on immigration has shifted considerably since Biden took workplace—and now, with Kamala Harris because the nominee, the Democrats are sending a far totally different message than they did in 2020. Considered one of Harris’s first marketing campaign adverts touts her expertise as a “border state prosecutor” who “took on drug cartels and jailed gang members” and reminds voters that as vp, she backed the “hardest border management invoice in a long time.” Harris’s warning to would-be migrants in 2021—“Don’t come”—is now the sort of factor a rising variety of Democratic voters appears keen to listen to. In February, a Gallup ballot discovered that immigration was an important challenge for voters. And in July, a ballot discovered that 55 p.c of American adults wish to see immigration to america go down—the primary time in additional than 20 years {that a} majority of voters have mentioned they need fewer immigrants within the nation.

Having satisfied the general public that unlawful immigration is uncontrolled, the nativist proper is now shifting its efforts towards limiting authorized migration. The Heritage Basis’s Venture 2025 to remake the federal authorities beneath a Trump presidency features a chapter on the DHS that recommends decreasing or outright eliminating visas issued to international college students “from enemy nations”; reimplementing USCIS’s denaturalization unit to strip sure naturalized residents of their standing; retraining USCIS officers to deal with “fraud detection”; eliminating the variety visa lottery; ending so-called “chain migration”; and making a “merit-based system that rewards high-skilled aliens as an alternative of the present system that favors prolonged family-based and luck-of-the-draw immigration.”

John Tanton, greater than anybody else, understood the facility of harnessing the general public’s fears and anxieties within the service of a broader political challenge. FAIR, CIS, and NumbersUSA’s public campaigns could have targeted on unlawful immigration, however the organizations had been based to undo the harms that Tanton believed stemmed from the authorized immigration facilitated by the Immigration Act of 1965. Venture 2025, if it involves fruition, could also be what he and his disciples have lengthy been ready for. The indefatigable Tanton, who died in 2019 after an extended battle with Parkinson’s, didn’t reside to see the very Democrats who as soon as chanted “Immigrants are welcome right here” embrace insurance policies of restriction. If he had, it’s onerous to think about that he would’ve been stunned. Within the 1989 oral historical past, Tanton mentioned that those that “deal on the earth of concepts” come to anticipate a typical trajectory: “The primary response of many individuals is to say, ‘I by no means heard of it earlier than.’ And the second response after they considered it for a bit was to say, ‘It’s anti-God.’ And the third response after they’d realized the concept was proper was to return round and say, ‘I knew all of it alongside.’”

We’d like your assist

What’s at stake this November is the way forward for our democracy. But Nation readers know the battle for justice, fairness, and peace doesn’t cease in November. Change doesn’t occur in a single day. We’d like sustained, fearless journalism to advocate for daring concepts, expose corruption, defend our democracy, safe our bodily rights, promote peace, and shield the surroundings.

This month, we’re calling on you to offer a month-to-month donation to assist The Nation’s impartial journalism. If you happen to’ve learn this far, I do know you worth our journalism that speaks reality to energy in a method corporate-owned media by no means can. The best option to assist The Nation is by turning into a month-to-month donor; this may present us with a dependable funding base.

Within the coming months, our writers might be working to convey you what it’s good to know—from John Nichols on the election, Elie Mystal on justice and injustice, Chris Lehmann’s reporting from contained in the beltway, Joan Walsh with insightful political evaluation, Jeet Heer’s crackling wit, and Amy Littlefield on the entrance traces of the battle for abortion entry. For as little as $10 a month, you’ll be able to empower our devoted writers, editors, and truth checkers to report deeply on probably the most vital problems with our day.

Arrange a month-to-month recurring donation right now and be part of the dedicated group of readers who make our journalism potential for the lengthy haul. For almost 160 years, The Nation has stood for reality and justice—are you able to assist us thrive for 160 extra?

Onwards,

Katrina vanden Heuvel

Editorial Director and Writer, The Nation

Extra from The Nation

To know the ambitions of the conservative majority, look no farther than Venture 2025, which was cooked up by a few of the similar individuals who engineered the present courtroom.

Function

/

Elie Mystal

You don’t must wield a T-square to profit from the sector’s first collective bargaining settlement in a long time.

Column

/

Kate Wagner

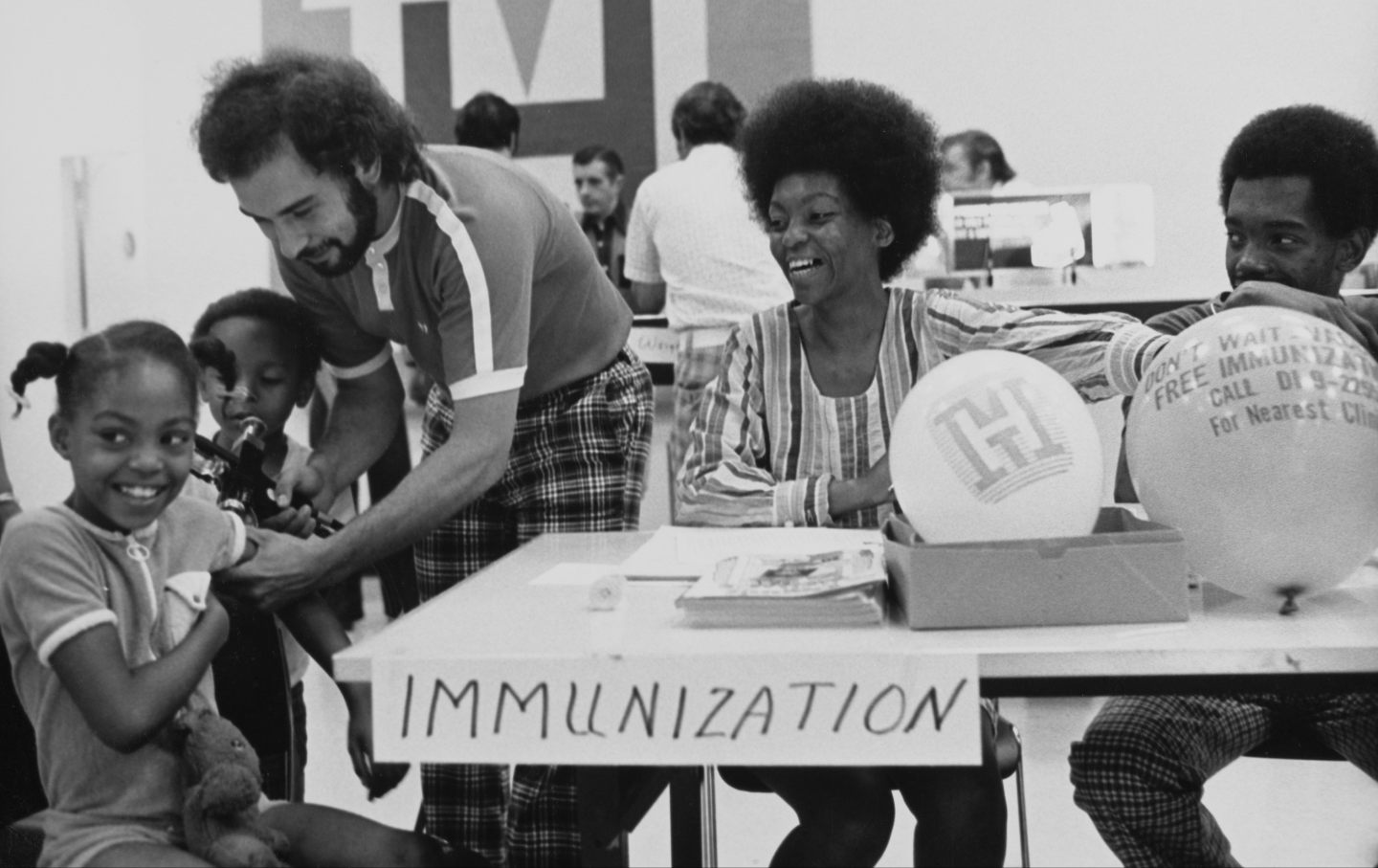

Need a simple option to shield your self, your family members, and your group? Ensure you get your photographs.

Gregg Gonsalves