The panic button hanging round Marcos’ neck evokes the demise menace that pulled him out of the Mexican mountain forests of the Sierra de Manantlán and dragged him to the outskirts of Guadalajara. After years of intimidation, he fled his hometown after the physique of his 17-year-old son was discovered mendacity on the aspect of a street. The boy was killed, the attorneys on the case say, as a result of, like his father, he opposed the actions of the Peña Colorada mine, which since 1975 has been squeezing the Sierra in quest of iron. Over the a long time, the iron mine, Mexico’s largest, has depleted the area’s water reserves, deforested its hills, polluted its air, and created divisions in the neighborhood.

On the finish of every day, after wandering a metropolis with partitions, monuments, and kiosks lined with the faces of lacking individuals, Marcos, who’s a part of the Indigenous Nahua peoples, takes off his panic button, a direct line to the native police. He not often sleeps. “My head kilos,” Marcos, whose actual identify Grist has determined to withhold because of latest demise threats towards him, mentioned. He thinks of his spouse, nonetheless at their farm in Ayotitlán, of the fallen fences, of the corn that no person takes to city, of the espresso beans that rot as a result of there isn’t a one to pluck them, of his remaining kids, of the vehicles that menacingly circle their home. The reminiscence evoked by the machine on his bedside desk can’t be eliminated. It’s a noose across the neck of a person who feels he’s been sentenced.

Greater than 13 defenders — largely Indigenous — of the Sierra de Manantlán have been murdered since 1986, in accordance with the nonprofit group Tskini, which works with Marcos’ group to defend their lands and other people. For hundreds of years, the area’s residents have been massacred and disappeared for demanding their proper to inhabit their ancestral lands. In latest a long time, this activity has gotten tougher, as extractive industries plundered the mountains.

Based on a report launched this month from the watchdog group World Witness, greater than two-thirds of the 18 activists killed in Mexico final 12 months had been Indigenous, against mining operations alongside the Jalisco-Colima-Michoacán Pacific coast, the place the Sierra de Manantlán is situated. The report named Latin America the deadliest area for environmental activists, accounting for 85 p.c of the 196 land defenders murdered globally in 2023.

However whereas public discourse and coverage have targeted on addressing essentially the most egregious circumstances of violence towards environmental activists — equivalent to assassinations, threats, or pressured disappearances — little to no consideration has been paid to the invisible traumas and psychological well being impacts skilled by those that defend the lives of rivers, mountains, ecosystems, animals, and the communities that dwell inside their bounds.

“Around the globe, those that oppose the abuse of their houses and lands are met with violence and intimidation,” the World Witness report reads. “But, the complete scope of those assaults stays hidden.”

Latin America’s environmental activists dwell amid a relentless menace of violence that permeates their days and our bodies and that, like polluted air, tears their insides aside.

Leaders expertise insomnia, nervousness, paranoia, panic assaults, melancholy, isolation, and suicidal ideation, mentioned Mary Menton, an assistant professor at Heriot-Watt College who works with environmental leaders in Brazil. “Some are unable to talk for days on the peak of a panic assault,” she added. A world examine of 110 human rights staff, lots of whom concurrently determine as or work with land defenders, discovered they undergo from post-traumatic stress dysfunction, demotivation, conflicts with friends, household issues, alcoholism and drug abuse, and somatization, or the bodily expression of psychiatric issues. An earlier on-line survey discovered that shut to twenty p.c of human rights defenders met all the factors for post-traumatic stress dysfunction and that just about 15 p.c had signs of melancholy.

In among the Latin American nations the place assaults towards environmental defenders are notably excessive — Mexico, Brazil, Colombia, and Honduras — governments have created safety mechanisms, offering bodyguards, satellite tv for pc cell telephones, and bulletproof vests, amongst different strategies, to ensure activists’ bodily security. Assist for psychological well being in these programs, nonetheless, is near nonexistent, mentioned Lourdes Castro, coordinator of the Somos Defensores program, which screens violence towards human rights defenders in Colombia. As a substitute, psychological care falls to non-public or nonprofit organizations, which don’t have the sources to satisfy the rising want — within the uncommon circumstances when land defenders are open to, and trusting of, that type of care. “We speak about the issue, the answer, the hearings, that there’s going to be a gathering, however not often about this,” Marcos mentioned.

“Most [activists] don’t have the cash to pay for it. And even when they did and had entry to someone,” mentioned Menton, “then there’s additionally the resistance to it. Some individuals, for comprehensible causes … they don’t belief very simply.” Added to this are the challenges of getting out and in of their territories — normally situated in distant areas — or the unstable connection to the web and phone sign for digital care.

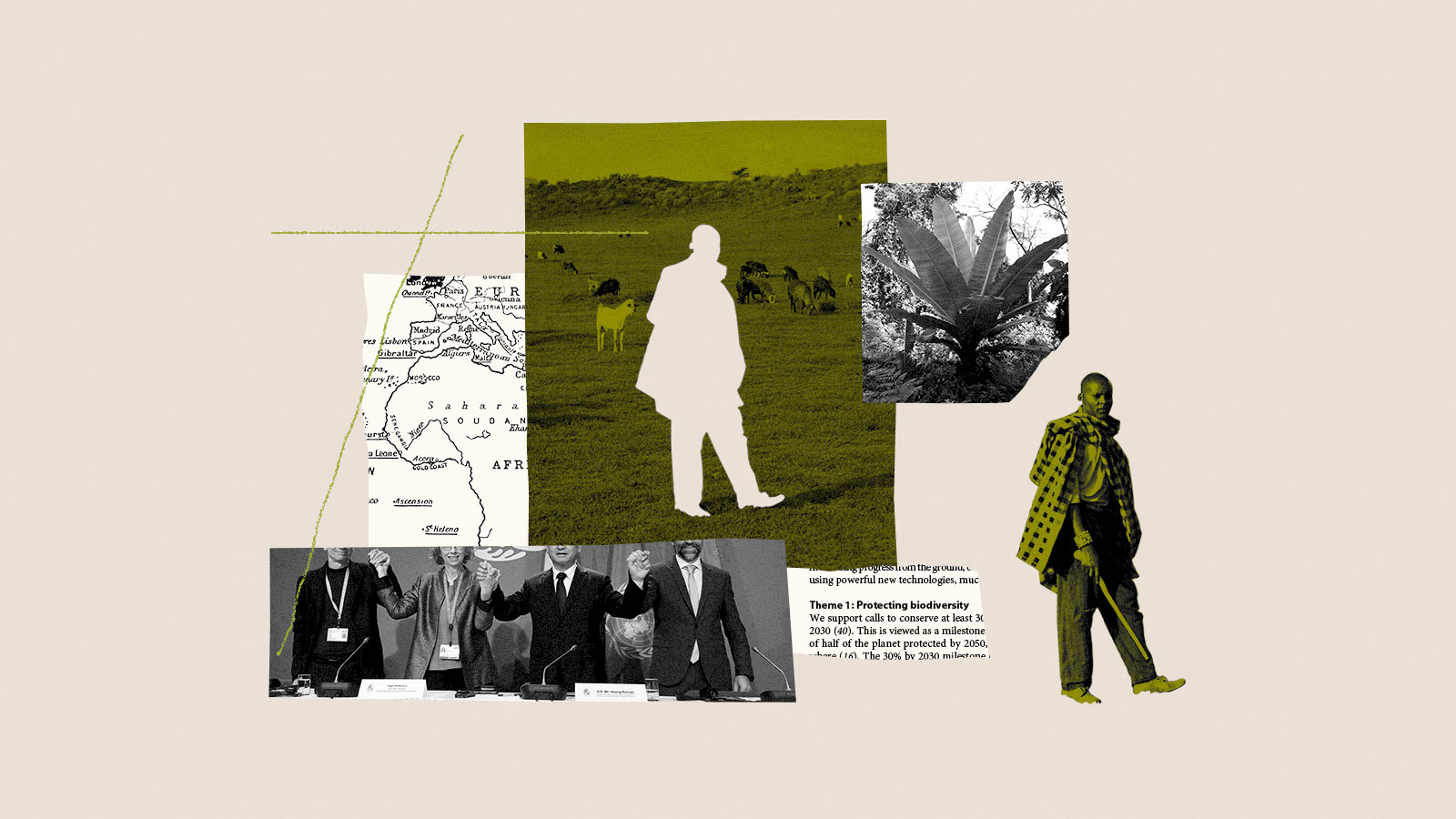

As a response, psychologists, social staff, and attorneys have been constructing a community of secure homes and non permanent shelters all through Latin America that help the psychological well being of social leaders and human rights defenders and, more and more, threatened environmental leaders. These shelters have turn into one of many few secure areas to cope with particular person and collective grievances, Menton mentioned. Past addressing a person’s psychological state, the remedy in these areas goals to deal with collective trauma, mentioned Clemencia Correa, a Colombian psychologist exiled in Mexico since 2002 due to her work with civil struggle victims.

Whereas the necessity to preserve the places of those locations secret makes it inconceivable to have clear figures relating to their existence, there are at the very least 10 shelters in Central and South America that make up this rising regional help community. By means of theater, artwork, and handicraft workshops, amongst different strategies, their psychosocial method is increasing past the shelter partitions and slowly permeating the work of environmental organizations as nicely.

“It’s normalized to dwell underneath fixed stress with psychological well being points,” mentioned Adriana Sugey Cadena Salmerón, a lawyer working with Marcos. In 2020, she and her colleague Eduardo Mosqueda based Tskini, the group that works with leaders of the city of Ayotitlán and locations psychological well being as a core precedence. “If we begin to concentrate, to look after one another, then I feel we’ll be stronger,” she mentioned.

Beginning within the Nineteen Forties, Marcos’ group, the Nahua, watched as logging firms, supported by native and nationwide governments, shaved the mountainous forests and grasslands of their ancestral Sierra de Manantlán. The area’s identify comes from the Nahuatl phrase “amanalli,” which implies “place of springs or weeping waters,” and it offers ingesting provides to nearly half 1,000,000 individuals throughout western Mexico.

Marcos’ father-in-law and Nahua chief spent a long time defending the Sierra de Manantlán and advocating for the popularity of Indigenous lands. He was despatched to jail in 1993 after main a type of protests. Marcos helped set up a rally to demand his fast launch in Telcruz, within the Mexican state of Jalisco. Police broke up the demonstration with gunfire. Two of these bullets discovered a spot to bury themselves: the our bodies of Juan Monroy Elías and José Luis, Marcos’ youthful brother. He was simply 22 years previous.

In parallel to this wrestle for land recognition, and after a long time of strain from environmental organizations and Indigenous leaders, the loggers finally left in 1987, when a lot of the Sierra was declared a protected space. However one main extractive business remained: the Consorcio Minero Benito Juárez-Peña Colorada iron mine, opened in 1975. The open pit mine, which spans over 96,000 acres, together with practically 3,000 of Nahua collectively owned lands, disfigured the panorama, changing inexperienced mountains with mounds of crumbled stone. Based on firm numbers, the mine produces 3.6 million tons of iron pellets yearly, and 4.1 million tons of iron focus, offering 30 p.c of Mexico’s business’s wants. Metal giants ArcelorMittal and Ternium — which personal and function the mine — didn’t reply to a number of requests for remark.

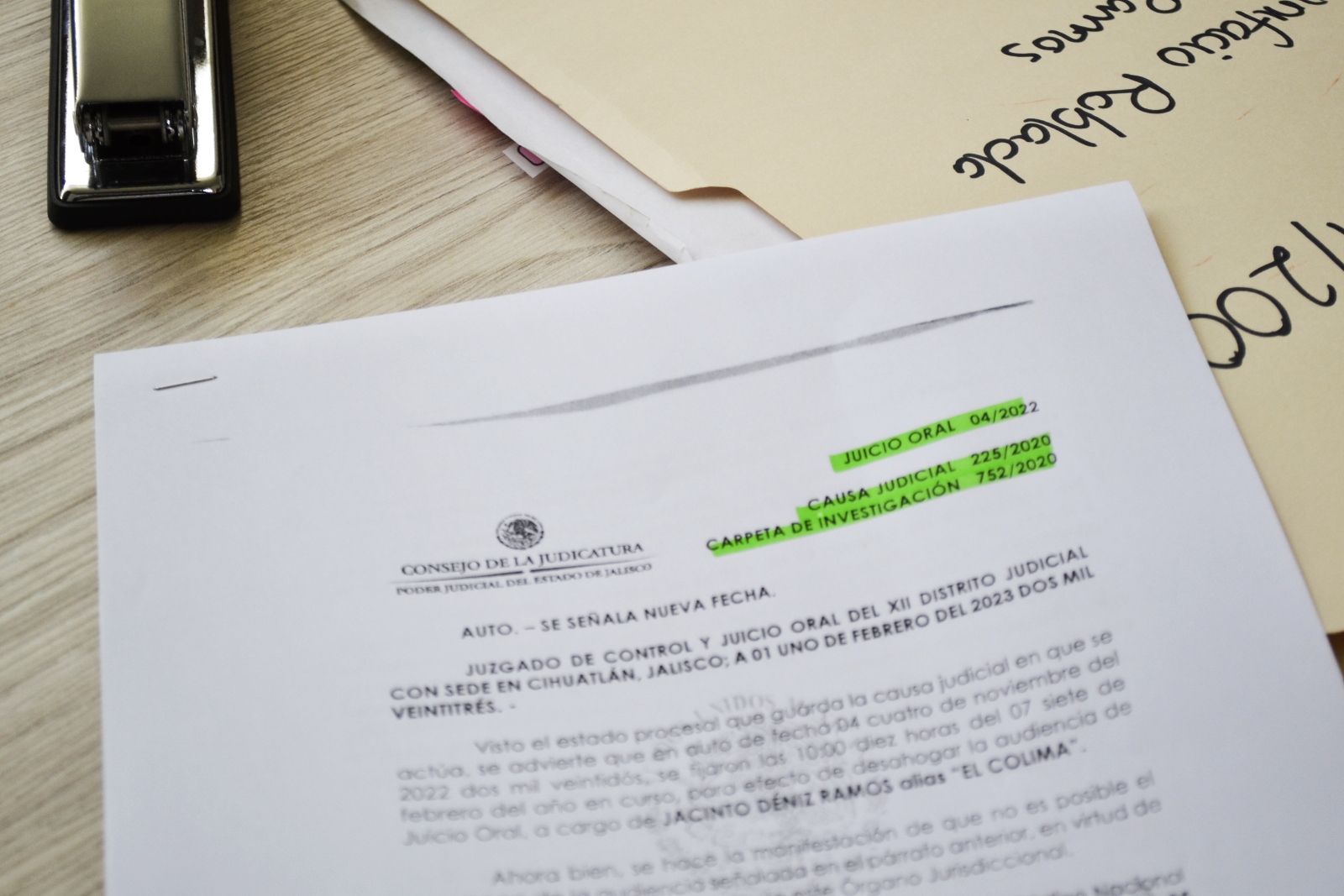

Murders, Menton mentioned, are simply one of many violent actions environmental leaders face across the globe. A number of organizations report that leaders are more and more going through threats, intimidation, judicial persecution, smear campaigns, repression, and every day microaggressions. The truth is, World Witness discovered that criminalization is now essentially the most used tactic to silence environmental defenders. Marcos has been detained thrice, the longest one lasting six days, throughout which he was overwhelmed by police in Guadalajara, he mentioned.

The intersection of all these types of violence — that occur throughout time, house, and even generations — creates a sense of everlasting aggression, Menton wrote in 2021. “Residing underneath this fixed menace creates what we’ve referred to as atmospheres of violence or climates of horror,” a gradual violence that usually goes unnoticed.

From the Nineties onwards, at the very least eight individuals all through the Sierra had been killed for his or her activism. Regardless of the creation of an ejido — legally acknowledged and collectively owned lands — in 1963, outsiders have infiltrated decision-making positions that govern the territory. After a controversial election course of in 2005, Jesús Michel Prudencio, a Peña Colorada worker, turned the ejido’s authorized consultant, referred to as the ejidal commissariat, and approved the growth of the mine. Subsequently, leaders from the group have been pressured to drop their campaigns towards company-friendly candidates, generally being murdered for not doing so. Paramilitaries quickly started to prowl the Sierra overtly, and the legal syndicate Jalisco New Era Cartel started opening unlawful mines on prime of its drug trafficking actions.

For 23 years, Marcos juggled his work as a college trainer with advocacy, generally instructing the youngsters of these in the neighborhood working for the Jalisco New Era Cartel. He led protests demanding cost from the mine for his or her use of group lands, pleaded with authorities officers for justice and collective safety, and was the face of lawsuits denouncing exterior interference within the governing of Nahua lands. However that balancing act ended on the morning of October 26, 2020, after his eldest, then 17, dropped him off at college. Hours later, Marcos noticed his physique mendacity on the aspect of the street in the neighborhood of Rosita. The highschool boy had begun to talk up on social media concerning the shady dealings of the ejidal commissariat. “I made the error of speaking concerning the abuses, which clearly bothered him,” Marcos mentioned. A 12 months later, he left Ayotitlán. He arrived in Guadalajara, Mosqueda, his lawyer, mentioned, “like a scared little mouse.”

“I nearly misplaced my thoughts,” Marcos recalled. He couldn’t sleep. When he slept, he had nightmares. And he feared — and nonetheless fears — persecution towards him. “I needed to discuss to clergymen, psychologists, [it was] laborious. I get over it, however little or no … I stroll round all day with issues, the sensation that one thing will occur.”

Two extra land defenders have been killed within the Sierra de Mantatlán since 2020. Certainly one of them was a part of the Nationwide Mechanism for the Safety of Human Rights Defenders and Journalists program, which offered bodily safety measures. The opposite homicide hasn’t been prosecuted. In 2023, Marcos acquired new threats, and a pick-up van parked exterior his house for 4 hours.

Marcos receives counseling from a psychologist paid for by Tskini, in addition to takes remedy. He’s additionally in graduate college, finding out for his grasp’s in academic pedagogy. He sees his spouse and kids each two or three months, when his pockets and security situations permit. “Police go to through the day, however at evening they go away, and the criminals are nonetheless free,” he mentioned. The Jalisco prosecutors’ workplace investigating his son’s homicide declined to touch upon an energetic investigation.

Regardless of its restricted sources, Tskini works with a psychological well being skilled who cares for Marcos, the group’s two attorneys, who additionally face threats by means of their work with leaders from Ayotitlán, and a second chief who additionally needed to go away his house and settle in Guadalajara. With out the group’s help, Marcos couldn’t pay the taxi and bus fare to the appointment, or purchase the drugs prescribed by the specialist.

Marcos mentioned defenders used to prepare to demand the discharge of their leaders, or they might go so far as Mexico Metropolis or Guadalajara to show abuses. Not anymore. At present, nobody needs to signal the police report requesting an investigation into the demise of José Isaac Santos Chávez, his colleague assassinated in 2021. Nobody needs to affiliate their identify with the wrestle for the Sierra. “They’re afraid,” he mentioned. “They know they’ll be harassed or pressured to vanish.”

In Purépecha language, from the central Mexican state of Michoacan, Tskini means “from the place one thing sprouts,” Cadena Salmerón mentioned. In a local weather of horror, she mentioned, “we’ve to be nicely, we’ve to be targeted, we’ve to have peace of thoughts.”

In a humble neighborhood south of Bogotá, Colombia, there’s a home so unremarkable that it’s simple to stroll previous. Apart from the cat that wanders the close by rooftops, its residents not often exit and by no means after 8 pm. They’re discreet, nearly as nondescript because the constructing itself.

There may be fierce persecution towards those that dwell there — threatened social and environmental leaders. Army helicopters have overflown earlier variations, searching for its inhabitants. Unknown males have entrenched themselves exterior. That’s why, every so often, the residents transfer and occupy one other unassuming constructing.

Behind the steel door, nonetheless, it’s something however bland. Within the again, in a colourful mural, a capybara, a jaguar, a snake, and a cup of espresso encompass kids taking part in within the solar; two girls weave the map of Colombia; flowers, roots, birds, guitars, and flutes sprout from a coronary heart. Images and posters of assassinated leaders cling on the sky-blue partitions of a room that doubles as a music house and library. A pale declaration of human rights hangs on the wall resulting in an enormous corridor within the again.

Music room and gathering areas within the Corporación Claretiana secure home south of Bogotá, designed to assist residents sort out psychological well being points that come up from their activism. Gustavo Torrijos/El Espectador & María Paula Rubiano A.

Inside, the residents — who normally keep for as much as three months — sleep in bunk beds, cook dinner and clear for one another, and spend their hours resting, studying, and speaking to one another and the therapists within the group. Some days, they go to the stitching room and work by means of their traumas through the use of their arms. Not all days are good: Typically somebody wakes up screaming at daybreak with a panic assault, during which case one of many psychologists rushes to the home to assist them by means of it.

“We’ve seen many generations develop,” mentioned Jaime Absalón León Sepúlveda, founder and director of the Corporación Claretiana Norman Pérez Bello, which runs the house and has been sheltering human rights defenders from throughout Colombia since 2003. “At first it was about saving individuals from being killed and having a secure place the place they may breathe, be with their household and start to grieve.” However he quickly realized they wanted “therapeutic areas, collective and particular person, to cope with the crises.”

The work in the home south of Bogotá relies, above all, on a department of psychology born between the bullets of the Central American civil wars within the ’70s and ’80s. Referred to as liberation psychology or psychosocial remedy, it’s a therapeutic various to conventional scientific work, specializing in conversations and instruments like theater, portray, writing, and different inventive endeavors that permit sufferers to place their particular person struggling inside a political context. The tactic later unfold all through Latin America, serving victims of Colombia’s armed battle; younger individuals within the Brazilian favelas, or casual settlements; family of the disappeared; and torture survivors of the Chilean and Argentinian dictatorships.

Quickly, facilities targeted on the psychological well being of human rights activists and land defenders began cropping up. In 2013, Correa, the Colombian psychologist, based Aluna, a corporation targeted on any such remedy in Mexico, the place she’s been residing in exile since 2002.

Correa left Colombia after serving to to uncover a navy intervention, referred to as “ Operation Genesis,” that had been deliberate by paramilitaries and the Colombian military to entry the fertile lands — good for agribusiness — and forests within the Colombian Caribbean, an space referred to as Urabá and near the Darien Hole. At first, she recollects, nobody was in a position to inform them what had occurred. “Individuals mentioned, ‘We don’t know, the unhealthy guys kicked us out,’” Correa says. “They couldn’t identify it.”

Everybody’s sense of id was shattered, separated from the land that they had lengthy referred to as house. Little by little, info began to trickle in: Our bodies started showing on the streets of Turbo, situated earlier than the beginning of the Darien Hole. No less than two native officers disappeared. Days earlier than the displacement in 1997, military helicopters dropped bombs over the world. “The monsters are right here,” the youngsters had mentioned. The navy got here to some villages to inform them that in the event that they didn’t go away in three days, they had been going to kill all of them. Then the paramilitaries got here in. They burned down the homes. They dismembered the physique of Afro-Colombian chief Marino López Mena in his small village on the banks of the Cacarica River.

“After we retraced these occasions with individuals, it was very painful. However with the ability to identify it allowed us to attempt to perceive in order that this might not be completely hushed up,” defined Correa. Correa and her colleagues related the operation to logging pursuits over the fertile lands of the Urabá area — a reality acknowledged a decade later by the Inter-American Court docket of Human Rights and, extra lately, by Colombia’s Reality Fee. With the allegations got here threats to Correa and others. After which, exile.

When she landed in Mexico, Correa instantly contacted environmental and social organizations. She realized that though the nation had not suffered a long time of bloody civil struggle like Colombia, because the late Fifties, when guerrilla teams began to seem throughout the nation, the federal government had waged a low-intensity struggle that, with the excuse of stopping insurgent organizations, attacked authorities opponents, leftist leaders, college students, and rural and Indigenous individuals. Correa noticed how this “soiled struggle” was based mostly on the identical terror ways utilized in Colombia: arbitrary detentions, torture, selective assassinations, massacres, and compelled disappearances. And, like in Colombia, victims felt responsible, oscillating between apathy and paranoia. Some didn’t sleep, others lived in concern. A number of drank excessively. All had been terrified.

Conventional psychology, developed by means of fastidiously manufactured and managed experiments on faculty campuses in the US, didn’t conceive the depth of those victims’ and activists’ wounds, Correa mentioned. Nor did it know how you can heal them. “We depend on communities’ capacities to construct resilience, which greater than resilience is resistance to maintain on residing,” León Sepúlveda defined about this line of labor.

Correa’s group, Aluna, as a substitute applies an method to sufferer help proposed by Ignacio Martín-Baró within the Nineteen Seventies. The Spanish psychologist and priest, who graduated from Chicago College, devoted his life to unraveling the impacts of political violence in El Salvador, the place a string of navy governments and conservative presidents violently repressed any protest towards social and financial inequality. Above all, Martín-Baró wished to search out methods to rebuild communities. His “liberation psychology,” because it’s identified, states that if the causes of a wound are from an oppressive political and social context, to heal, individuals and communities ought to first perceive that context and its key gamers. Then, after going through the impacts of that violence with psychosocial help, victims might shed their trauma and reaffirm themselves as political actors.

This new method of understanding their actuality permits them to rebuild themselves personally and collectively, “enabling them not solely to find the roots of what they’re, but additionally the horizon of what they’ll turn into,” Martín-Baró wrote in 1985. Below this technique, therapeutic is known as a political act of freedom. 4 years later, in 1989, Martín-Baró was assassinated by the Salvadoran military on the Central American College, the place he was the pinnacle of the psychology division.

After the priest’s assassination, his pondering unfold throughout Latin America. In 1998, the primary Worldwide Congress of Liberation Psychology was held in Mexico Metropolis, then held yearly till 2005 (since 2008, it was held each two years till 2016). Professionals from everywhere in the area gathered to change concepts, experiences, and strategies. In 2008, Correa joined the gathering to speak about counseling victims of sexual torture. Round that point, León Sepúlveda had opened the doorways of the primary secure home of the Norman Pérez Bello Company, furnished with a few armchairs and beds donated by the Roman Catholic Claretian order, which he had deserted. The earliest residents had been victims of Colombia’s inner battle, however all through the years, it has hosted LGBTQ+ rights activists, youth advocates protesting the dearth of alternatives in cities, victims of state violence and, extra lately, environmental defenders.

In observe, psychosocial counseling takes many types, mentioned Ajax Sanhueza, director of Colectivo Casa, a human and environmental rights advocacy group working with Indigenous leaders in Bolivia since 2008. They labored with girls from the Pink Nacional de Mujeres en Defensa de la Madre Tierra, or the Nationwide Community of Ladies in Protection of Mom Earth, who determined they wished to create quick movies during which handmade dolls dressed as Bolivian cholas, consultant of the threatened Indigenous leaders that voice them, denounce how mining actions threaten the water provides of many Indigenous tribes, in addition to calling for girls’s self-care.

Individuals should perceive what has occurred to them, on particular person, collective, and historic ranges, Correa defined. Suppose individuals don’t perceive, for instance, that their territory is a gorgeous place for sure industries or unlawful economies. In that case, it’s tough for them to make sense of the fear they expertise and take the suitable steps to guard themselves, she famous.

It’s laborious to inform what number of organizations have used or presently use any such remedy in Latin America. Mark Burton, a social psychologist who has studied this development since its inception, wrote in 2004 that training psychologists don’t systematize their experiences. Correa mentioned that the dearth of educational manufacturing is due, partially, to the truth that Latin American universities haven’t been within the observe for greater than a decade. Diploma programs and lectures on the topic, such because the Martín-Baró Worldwide Seminar on the Javeriana College in Colombia or the diploma course for forcefully disappeared lacking individuals on the Autonomous Metropolitan College, Cuajimalpa, don’t permeate the curriculum of psychology colleges, she mentioned. “There’s plenty of prejudice towards speaking a few political method, as if it will take away from the rigor of psychology,” she defined. Correa famous that such a place negates the truth that conventional psychology already carries ideological baggage. “Certainly one of Martín-Baró’s missions is the liberation of psychology itself.”

However networks do exist. As violence towards environmental leaders in Brazil escalates, “this difficulty of psychological well being help and psychotherapy stored arising repeatedly and once more,” Menton mentioned. Current protocols are inadequate. “When you’re in the course of a disaster, the final place you need to be is in a chilly lodge room in a metropolis the place you don’t know anybody, and also you don’t have a help community,” she mentioned. “We had been questioning, how will we create areas to heal? That is all rising underneath the floor, and the thought of a home was there, like a dream.”

In 2018, after years of ruminating, Menton led the acquisition of a property within the Brazilian Amazon with the group Not1More and the Zé Claudio and Maria Institute. Aluna contributed its experience by coaching volunteers in Brazil on psychosocial ideas. Casa La Serena, a shelter situated in Mexico Metropolis, has helped Menton and her colleagues think about what facilities the home ought to have in order that its inhabitants “really feel secure,” she mentioned, “really feel that it is a place to breathe, sleep and relaxation.” Up to now, at the very least 4 adults have stayed in Casa de Respiro, and dozens have participated in workshops on self-care and holistic methods for coping with trauma, Menton added.

On the Corporación Claretiana home south of Bogotá, a stitching workshop has been the primary car for offering help, León Sepúlveda mentioned. Residents collect in a small house subsequent to the massive mural room each Saturday to speak and stitch. “The names [of the activities] listed here are all about reactivating the probabilities of life. [That space is called] ‘Mending our historical past, weaving hope,’” León Sepúlveda mentioned. “Individuals discuss, there’s a catharsis there.”

In 2023, after 20 years in exile, Correa was reunited in Bogotá with León Sepúlveda, whom she had first met when he was younger pupil priest who typically gave refuge to rural farmers, Indigenous peoples, and Afro-Colombians fleeing struggle. Convened by the worldwide group Bread for the World, about 10 psychological well being shelters situated in Colombia, Mexico, Brazil, Costa Rica, Honduras, and Guatemala are a part of an effort, nonetheless in its infancy, to relocate essentially the most at-risk leaders all through the area. Additionally, Correa mentioned, they wish to create secure havens in rural areas, as one of many largest challenges for leaders is adapting to a metropolis way of life.

Caring for individuals who care for his or her communities and territories is a dangerous and generally traumatic job. León Sepúlveda has been threatened a number of instances, and a few of his closest collaborators have been killed. To deal with the burden, the defender performs Andean music along with his kids and pals, works within the fields, and writes poetry. Like the home’s inhabitants south of Bogotá, he can’t think about abandoning his mission.