Suicide pod technology in Switzerland sparks debate as solo capsules evolve into couples devices and AI-assisted death tools.

Two years ago, the controversial suicide capsule known as Sarco shocked global audiences and reignited debates around assisted death. At the time, many believed the discussion had reached its limit.

Few imagined that the story would continue in such an unsettling direction.

The First Sarco Death and an Unfinished Investigation

In September 2024, a sixty four year old American woman entered a Sarco capsule in a secluded forest in Switzerland. After activating the device, she became the first recorded person to end her life using this machine.

Sarco functions by replacing breathable air with nitrogen, causing rapid loss of consciousness and eventual death. Its creator described the process as peaceful and free of pain.

Swiss authorities disagreed. Assisted suicide through such devices is not legally permitted under Swiss law. Shortly after the incident, police arrested Florian Willet, the operator present at the scene.

As the investigation progressed, troubling details emerged. Police stated that the woman may not have died immediately. Evidence suggested movement inside the capsule, possible struggle, and marks on her neck. What began as a case of illegal assisted suicide began to resemble a homicide inquiry.

No decisive evidence was ever found. Willet was released, but the psychological impact was severe. The following year, he died by suicide himself.

The Inventor and His Refusal to Stop

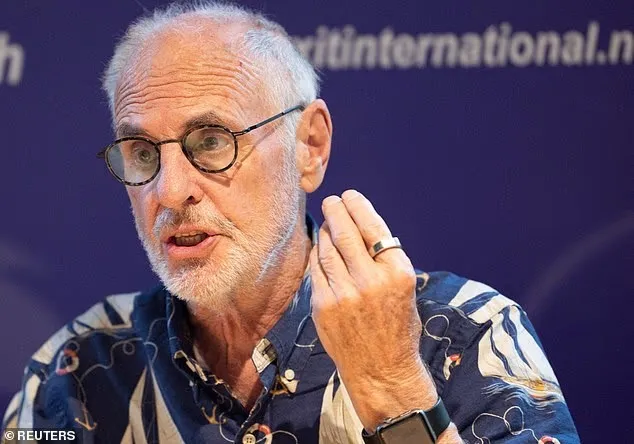

Sarco’s inventor, Philip Nitschke, expressed deep regret over Willet’s death. He blamed prolonged detention and sensational media coverage for pushing his colleague into despair.

Despite the tragedy, Nitschke did not retreat. Instead, he announced plans for a new generation of suicide devices, including one that immediately drew widespread condemnation.

A Capsule Designed for Couples

The new design is known as the Double Dutch Sarco Pod. Unlike the original capsule, this version is built for two people.

According to Nitschke, many long term partners wish to die together. Some fear facing death alone. Others describe solitary suicide as emotionally unbearable.

This couples capsule is twice the size of the original. It is explicitly designed for partners who wish to end their lives on the same day and at the same time.

Two Buttons and a Shared Decision

The activation mechanism is deliberately strict. The capsule contains two separate buttons. Both must be pressed simultaneously.

If only one person presses their button, the system will not activate. The rule is simple. Either both participants consent fully, or nothing happens.

The intended method of death remains nitrogen exposure.

Artificial Intelligence and Mental Capacity Testing

One of the most controversial changes involves psychological evaluation. Traditionally, individuals seeking assisted suicide must undergo professional mental health assessments.

Nitschke proposes replacing doctors with artificial intelligence. An AI system would evaluate whether the applicant understands the decision and is mentally competent.

Once approved, the capsule remains operational for twenty four hours. During that period, users may enter and activate it. If time expires, the assessment must be repeated.

Nitrogen Death and Global Controversy

Nitrogen based death has long been disputed. Even before Sarco, nitrogen had been used in capital punishment.

In the United States, the state of Alabama introduced execution by nitrogen hypoxia. Officials claimed the method was humane.

Witness accounts tell a different story. Several executions involved visible distress, violent physical reactions, and prolonged death.

In October 2024, convicted murderer Anthony Boyd was executed using nitrogen. Observers reported gasping, convulsions, and nearly forty minutes of visible struggle before death was declared.

Nitschke argues these cases differ fundamentally. Prisoners resist death, he claims. People who voluntarily enter a suicide capsule do not.

Critics remain unconvinced.

Legal Resistance in Switzerland

Swiss authorities have not accepted Nitschke’s reasoning. Investigations into whether Sarco constitutes illegal assisted suicide remain ongoing.

Until legal conclusions are reached, neither the original capsule nor the couples version can be officially deployed in Switzerland.

Moving the project abroad is equally difficult. Many countries impose strict medical criteria, often requiring terminal illness or irreversible physical suffering. Swiss regulations are comparatively lenient, making relocation impractical.

A Wearable Alternative: The Kairos Kollar

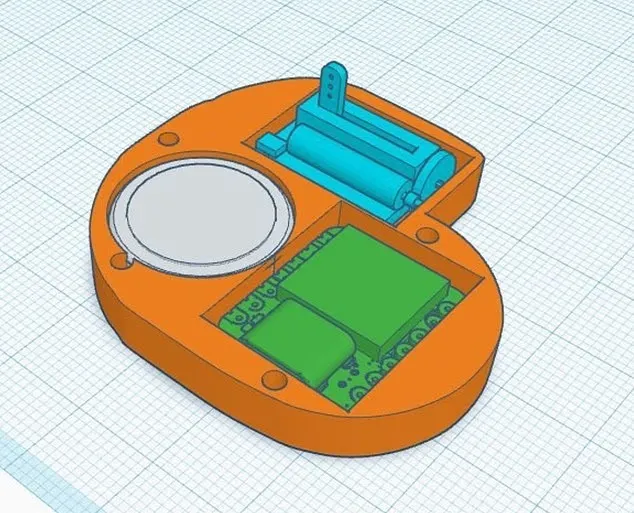

To bypass legal restrictions, Nitschke developed another device called the Kairos Kollar.

The name comes from Kairos, a Greek concept referring to a decisive or opportune moment.

Unlike the capsule, this device is worn around the neck. It applies pressure to critical arteries and sensory receptors, reducing blood flow to the brain and causing loss of consciousness followed by death.

The collar connects to a small inflation system controlled via a mobile application.

Nitschke openly praised its advantages. He described it as durable, permanent, and impossible to interrupt once activated. It is designed for home assembly, which he believes helps avoid regulation of assisted dying devices.

A Suicide Implant for Dementia Patients

Nitschke has also proposed an implantable death mechanism for people with dementia.

The implant contains a timer that emits daily sound and vibration alerts. If the patient fails to deactivate it due to cognitive decline, the device releases a lethal substance inside the body.

According to Nitschke, this solves a moral dilemma. Dementia patients often lose the mental capacity required to consent to assisted death. The implant allows them to decide in advance, without needing approval later.

Divided Public Opinion

Public reaction remains sharply divided.

Supporters argue that individuals deserve control over the timing and manner of their death. Some compare human assisted dying to euthanasia for terminally ill pets, framing it as an act of dignity.

Critics see something darker. They accuse Nitschke of targeting vulnerable populations and turning death into a consumer product.

The debate offers no simple answers. Attitudes toward death vary across cultures, beliefs, and personal experience.

One question remains unresolved. If death becomes effortless and accessible, what happens to humanity’s instinct to survive?